Wayne Shorter might best be known for his playing with Miles Davis and as a founding member of jazz fusion super group Weather Report. But amid the commercially successful albums, Shorter took time out to explore conceptual solo projects. Around the early 1970s, he recorded a run of acclaimed albums for Blue Note that embraced free jazz and Brazilian fusion.

As a new decade came into view at the end of the 1960s, jazz was expanding its horizons at full speed. Finding himself on the crest of its splintering configurations was Wayne Shorter, the sax player who Miles Davis called his “intellectual musical catalyst.” Since 1964 Shorter had been a key player of Davis’ second great quintet, and had helped guide the group through such historical sessions as “In A Silent Way” and “Bitches Brew”.

Shorter had been leading his own sessions for Blue Note alongside his tenure with Davis, but by 1969 he had reached a newfound artistic confidence, perhaps buoyed by the critical success of Miles’ early fusion albums, and was looking to take his music in a different direction. While the jazz-rock storm on “Bitches Brew” felt on the verge of spilling over into chaos, Davis always kept a tight rein on the band. This was in contrast to Shorter’s approach.

In Shorter’s biography by Michelle Mercer, bassist Dave Holland explained that “Miles liked things to be kept fairly clear behind him. He liked the groove to be kept consistently, not messing with the groove or making it too elastic. And also, he adhered to the form of songs. Obviously there’s a lot of freedom in his playing, but Wayne by contrast was just ready for anything to happen. We sensed that, and it gave us a sense of a little more freedom with Wayne in the music.”

Shorter was willing to embrace the chaos a little more than Davis, and in 1969 Shorter recorded “Super Nova,” his eleventh solo album and seventh for Blue Note. The album plays out like late night jams from the “Bitches Brew” sessions, which had been recorded only a week earlier. But “Super Nova” marked a difference from Shorter’s previous Blue Note albums – namely the exploration of Brazilian and Afro-Cuban rhythms and compositions, particularly on a version of Jobim’s “Dindi,” precipitated in part by percussionist Airto Moeira’s presence.

Performed in duet by Walter and Maria Booker before expanding into a batucada drum workout, “Dindi” bristles with emotion, as Maria’s voice breaks into sobs. This version was a good example of what Shorter wanted to capture in his music – the emotion, the soul, the journey to the inner constellation.

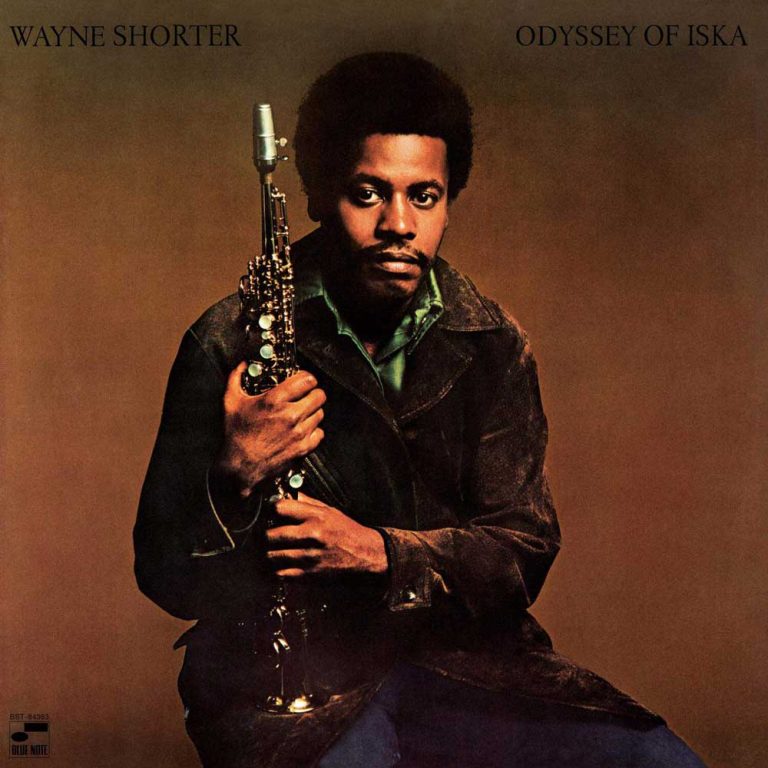

The soul is a theme that Shorter returns to on the following album “Odyssey of Iska.” In the liner notes, Shorter writes: “Iska is the wind. It’s like a breeze that comes and goes without leaving any trace. It’s Nigerian – not exactly a Nigerian word, but a poetic expression. It represents the transition of each man’s soul as it passes through life; a pictorial-musical journey symbolizing the lifetime and whatever happens after.”

Shorter’s daughter Iska was born in September 1969, but tragically suffered debilitating seizures. She was something of a catalyst for the saxophonist, as he looked for music with a deeper spiritual resonance, longer forms with more harmonic space to improvise, and less anchored in the corporeal. Shorter’s compositions were liberated yet determined: at the same time as he crafted the world-beat free-jazz tone poems to the planet that would comprise “Odyssey of Iska,” he decided it was time to step out from Davis’ group.

WAYNE SHORTER Odyssey of Iska

Available to purchase from our US store.In collaboration with other players, Shorter often sat back, allowing them to dictate the length of compositions. But on his own, Shorter stretched out songs until they became meditations on time, a communion with the continuum. On albums like “Odyssey of Iska” and its follow-up “Moto Grosso Feio,” we get a clearer glimpse of the musician, and also the Nichiren Buddhist that Shorter was: meditative, spiritual, peaceful, and a bit mystical.

There’s a story that once on a Weather Report tour, a friend asked Shorter the time, and he started talking about the cosmos and how time is relative. Zawinul came over and said, “You don’t ask Wayne shit like that. It’s 7:06 pm.” As perhaps the greatest soprano player after Coltrane, Shorter might have always been melodically on the move, but it was in this higher state of consciousness where he felt most at home.

Max Cole is a Düsseldorf-based writer and music enthusiast who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

Header image: Wayne Shorter. Photo: Michael Putland via Getty.