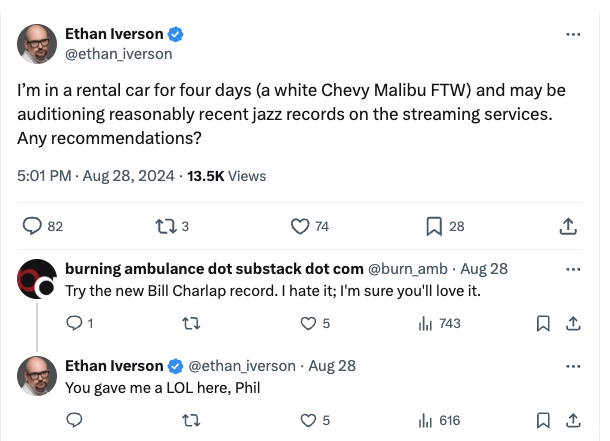

A few weeks ago, I put out a call on Twitter for suggestions of recent records to listen to.

Writer Phil Freeman joked, “Try the new Bill Charlap record. I hate it; I’m sure you’ll love it.”

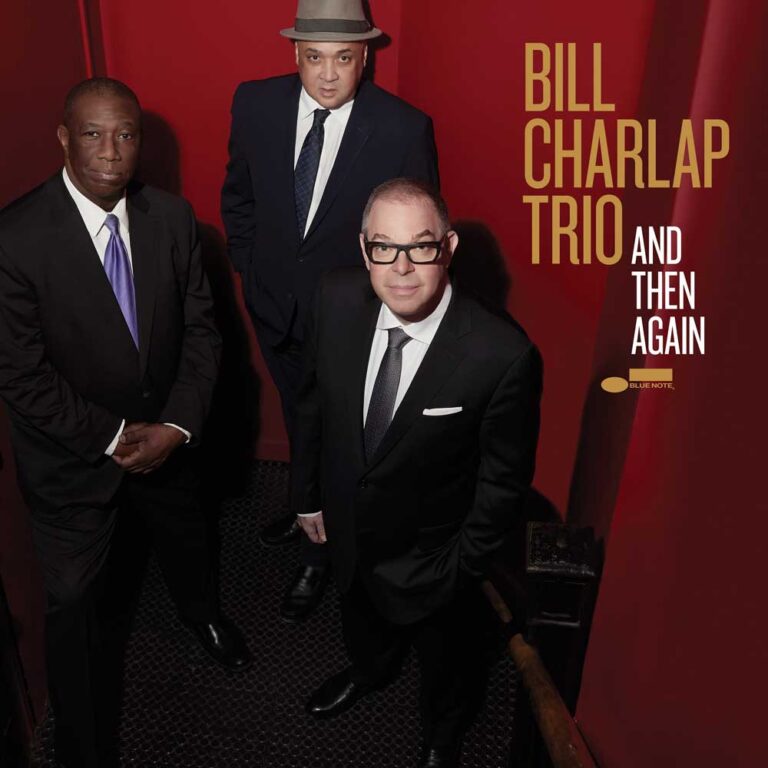

Actually, Freeman was right, I did love it, and I reviewed “And Then Again” with Peter Washington and Kenny Washington on my Substack.

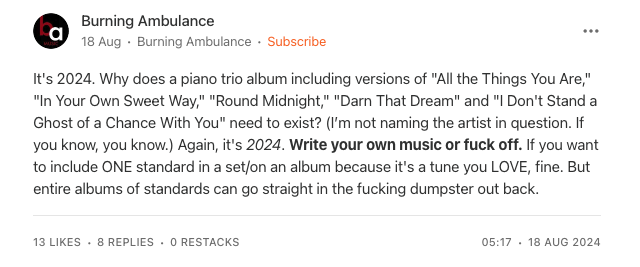

Freeman is particularly bothered when a new jazz album has a prevalence of familiar standards, and — never one to shy away from churning up the internet a bit — had already put up a raging subtweet about the Charlap album on all feeds.

I have a lot of sympathy for Freeman’s position. There are too many records to begin with, a lot of standards sound overly familiar in the hands of unexciting contemporary musicians, and Spotify playlists in coffee shops are clogged further with deliberately bland reenactments of old tunes on channels like “Jazz for Study” and “Lazy Jazz Cat.”

Yet there’s no one metric to what makes a great album. Compositions vs. standards, improvised vs. arranged, old vs. new — all of it can pass or fail.

In Bill Charlap’s case, he has a lifetime of deep investment in the American Songbook, and he works very hard to make his interpretations fresh and distinctive. When I called Bill to talk about his new record, the first thing I said was, “Well, I’ve just been practicing ‘All the Things You Are’ with minor major seven chords.” Charlap laughed. The first two bars of “All the Things You Are” are always minor sevenths, forever and a day — except that Charlap mixes it up and also plays minor major sevenths. In a mild-mannered way, this harmonic sleight-of-hand is radical. There are similar radical choices through out the whole setlist of “And Then Again.”

[Editor’s note: there is only a semitone (half step) difference between these two chords, but converting the minor seventh into a major is a noticeable change, the music takes on an edgier, more mysterious atmosphere]

Then there is the issue of what sparks band chemistry. On so many records and gigs, ensembles sound fresher and looser on familiar material. This is why the great experimentalists John Coltrane and Miles Davis kept playing standards during the upheavals of 1960’s innovation.

It’s very hard to write a good tune. Indeed, it almost seems easier to write more notes on the page than less. Have the advent of computer music notation programs like Sibelius, Finale, Musescore, and Dorico have been bad for jazz? Now everyone can input many little notes into a score, print it out, and — presto! — they are a composer. This “easy entry” may actually be a little too democratic, for all too often those many notes entered in a computer file do not tell a meaningful and memorable story. There are plenty of great jazz players active today who could cut down on their time fiddling with notation programs; rather, they could include a few more standards in their set.

Indeed, there’s nothing like a well-chosen standard to showcase the concept of all members of a band.

Phil Freeman’s latest book is In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor. It’s an excellent read, highly recommended, and somehow the first book-length study of one of the most significant pianists.

I like Cecil Taylor (I like Jimmy Lyons even more) and have listened to a fair amount of the Taylor discography. But, you know, after a while, it can all sort of sound the same. It’s great, but it is a bit monochromatic.

One of my favorite Taylor tracks is from early on, a 1960 deconstruction of the Rodgers/Hammerstein standard “This Nearly Was Mine.” This is one of the last standards Taylor ever recorded. In my view, Taylor’s later epic discography (over 70 records from the 1960’s through the 21st-century) would be even more appealing if he had kept playing a few more melodies from the Great American Songbook. Indeed, if Taylor had made an all-standards solo piano album, I bet I’d listen to it all the time.

Read on…Ten: Jason Moran and the Bandwagon’s Triumphal Tardis

Ethan Iverson is a prolific pianist, composer and writer. A former member of The Bad Plus, his latest record, Technically Acceptable was released on Blue Note in 2024

Header image: Ethan Iverson. Photo: Monica Frisell.