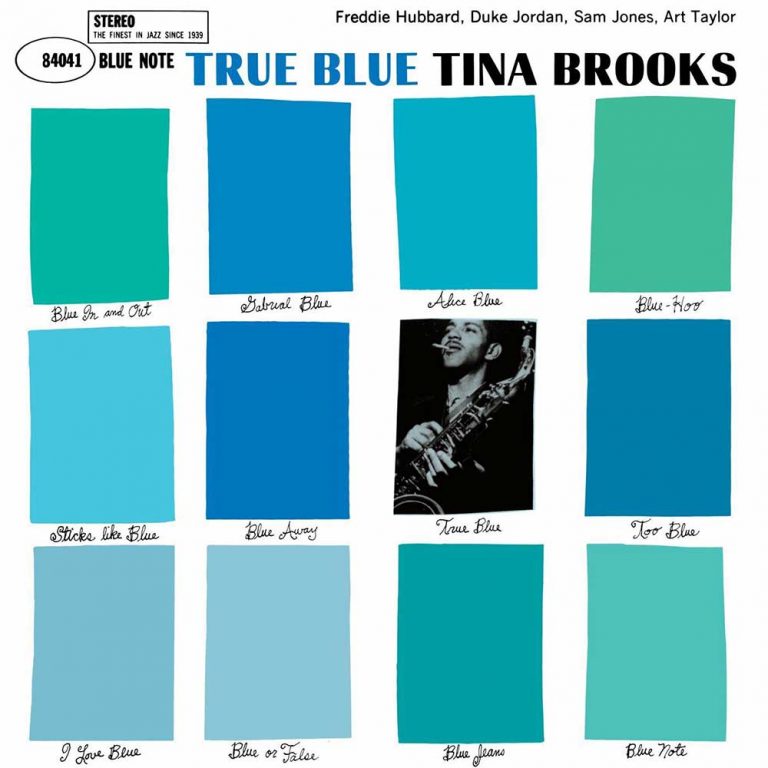

Like many classic albums, Tina Brooks and his hard bop masterpiece “True Blue” amounts to much more than the sum of its parts. While the album is a shining example of the classic hard bop style, with elegant compositions and blistering solos, it also serves as an epitaph of sorts to an overlooked tenor man who for a short moment blew with the greats and posthumously has come to be recognised as one of jazz’s truest souls.

By the time Brooks had graduated in 1949, he had moved from Fayetteville, North Carolina to New York City and was already playing professionally. Over the next years he worked with vibraphonist and bandleader Lionel Hampton as well as pianist-composer Elmo Hope. But his big studio break came when trumpeter Little Benny Harris called up Blue Note chief Alfred Lion and told him to get down to a Harlem club to check Brooks out. By spring 1958, Brooks was recording in sessions with organist Jimmy Smith and later with guitarist Kenny Burrell. Sandwiched between those dates was Brooks’ debut session as band leader for his album “Minor Move.”

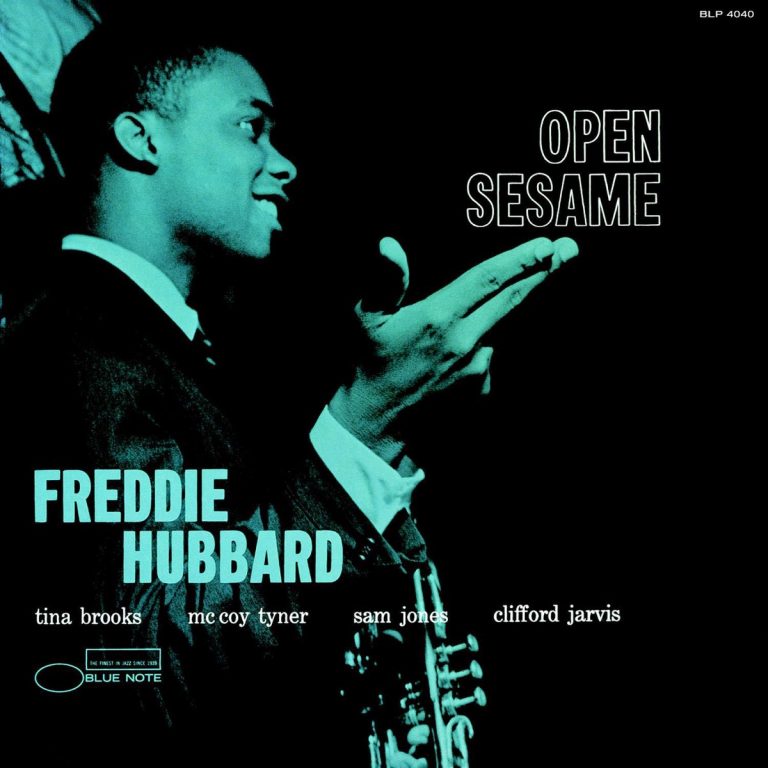

“Minor Move” wasn’t released at the time, but whichever vital ingredient was missing, it was there for the second chance Brooks got. The “True Blue” session found him at Englewood Cliffs with a different line-up from before, but no less impressive. Pianist Duke Jordan already had an excellent reputation playing with Charlie Parker and Stan Getz. Sam Jones was the regular bassist for Cannonball Adderley, and drummer Art Taylor had played with everyone from Coltrane and Miles to Monk and Donald Byrd. The extra spice in the session was a young trumpeter named Freddie Hubbard who had already caught the ear of Eric Dolphy and Wes Montgomery, and Brooks and Hubbard found they were on the same wavelength. Just a week earlier, Brooks had played on Hubbard’s debut solo album “Open Sesame”, and written two pieces, including the title track. Hubbard returned the favour by joining the recording session for “True Blue,” and their synergy is palpable.

At this time in 1960, jazz was in transition, and the style we know as hard bop was becoming more established. As the bebop vanguard had grown quieter, other adventurous players were looking to expand their horizons in jazz, and incorporate different musical styles, such as R&B. The Jazz Messengers, Lee Morgan, and others slowed down the tempo, shifted to more minor modes, and incorporated more Caribbean and eastern influences. In this hard bop landscape, Tina Brooks stood out a mile, possessing an enviable ability to compose open-ended harmonic figures and minor key signatures which were so blue they verged on the anguished, yet were still sophisticated.

While the compositions on “True Blue” are well-constructed, it’s the solos that have made this rare album so sought-after. Tina’s lyrical twists through the harmonic changes are brimming with feeling. Hard bop historian David Rosenthal describes Brooks’ playing on “True Blue” as “at once melancholy and muscular, and the brooding quality of his compositions determine the overall mood.” This is especially striking on “Theme For Doris,” where Rosenthal notes that “Tina reaches a pitch of sorrowful eloquence, vertebrated by Art Taylor’s driving beat, that lifts him for the first time to the level of the great jazz storytellers.”

But there’s even more to “True Blue” than the beautiful playing and the snapshot of hard bop history. Brooks’ recorded only a handful more times, and he died penniless at the age of 42. Were it not for Blue Note discographer Michael Cuscuna, who gained access to the Blue Note vaults in 1975 and discovered the tapes for Brooks’ three other unreleased albums, Brooks’ musical legacy would appear very different. His story might be one of tragedy and what-ifs, but it’s also one of second chances – salvation and rediscovery, rescue and reappraisal. “True Blue” is not just a wonderful example of hard bop jazz, it’s also part of a wider story, an almost biblical tale. Not even the vaults could hold Tina Brooks back, and his soul blows as strong as ever.

Max Cole is a writer and music enthusiast based in Düsseldorf, who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

Header photo: Francis Wolff/Blue Note Records