At the end of the 1950s, Miles Davis’s sextet was just about the slickest group in jazz. The trumpeter’s legendary ability to spot talent meant the band he’d assembled featured the best in the business: tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, alto saxophonist Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley, pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb. By the beginning of 1959, this unit were creating some of the most assured hard bop ever heard, and on March 2nd they helped make jazz history by entering the studio to record the Davis original “Freddie Freeloader” for his game-changing album “Kind Of Blue” (the rest of the album featured the same band with Kelly’s predecessor, Bill Evans, replacing him on piano).

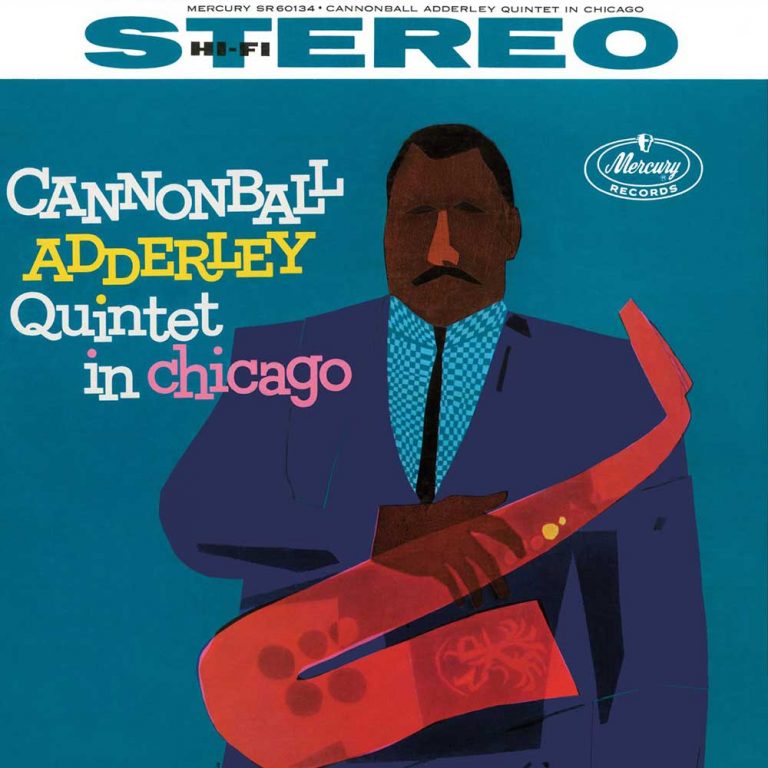

While “Kind Of Blue” pioneered the development of modal jazz, “Freddie Freeloader” was a more conventional blues with deeper roots in the music’s history. More in this vein can be heard on “Cannonball Adderley Quintet In Chicago,” recorded a month earlier on February 3rd 1959 at Universal Studio in the Windy City. The line-up is essentially Davis’s band without the trumpeter himself, leaving it to the two saxmen to lead the date (the album was reissued in 1964 as Cannonball & Coltrane). On the surface, it’s a relaxed and fun session featuring blues and ballads, standards and originals. But it’s also an opportunity to study the two sax players’ divergent personalities as they pull in very different directions.

That’s thrillingly apparent on the opening track – a breezily upbeat dash through the 1920s show-tune “Limehouse Blues.” After a brief intro, Adderley takes the first solo, instantly revealing his deep debt to bebop and particularly the virtuosic flights and flourishes of Charlie Parker. When Coltrane’s tenor drops in for a solo, it’s a startling contrast: while just as fleet-fingered, his sound is palpably more serious and searching, as though trying to discover something new. While Adderley leans on the past, Coltrane is scanning the future. The difference is laid out further in a couple of standard ballads on which each saxophonist gets a chance to be the sole horn – Adderley ebullient on “Stars Fell On Alabama,” and Coltrane soulful on “You’re A Weaver Of Dreams.”

The handful of originals show marked contrasts too. Adderley’s “Wabash” is a jaunty swinger with the alto hip and loquacious, throwing out more tightly coiled Parker-ish phrases peppered with hints of sanctified gospel shout. Coltrane’s two compositions have a tougher edge: “Grand Central” is racing hard bop with a more complex, syncopated structure; and “The Sleeper” is a mid-tempo, noirish blues that gives Coltrane his best opportunity to really blow. Here he’s testing the horn – straining at the upper registers and plumbing the depths – in pursuit of a more abstract personal lyricism.

Just a few months later, in May 1959, Coltrane began recording Giant Steps, his landmark album with Chambers on bass, joined by Kelly and Cobb on the timeless ballad “Naima.” It marked an intensification of the search heard incubating in Chicago – a step from which there was no coming back.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images.