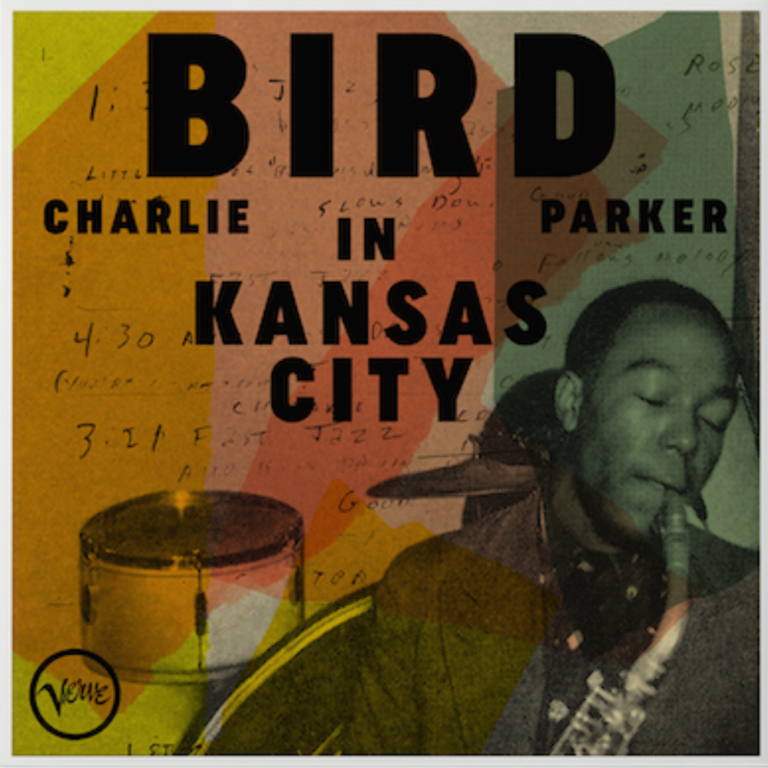

A new collection of rare private recordings offers us an insight into Bird’s formative development, as he honed the chops and improvisational techniques that would later turn the jazz world upside down with the creation of Bebop, alongside Dizzy Gillespie and others. We spoke to jazz historian, author and archivist Chuck Haddix, who wrote the liner notes and compiled this revelatory collection of recordings.

“This collection gives us a different perspective on Charlie Parker’s growth as a musician,” explains Haddix on a call one autumn afternoon, “and about two thirds have never been released or heard before!”

The timeframe of this collection is the decade from 1941-51, and the earliest recordings immediately set a remarkable tone. In February 1941, Parker was playing with jazz pianist and singer Jay McShann and his band, and the band’s manager John Tumino wanted to record the band in preparation for a recording session in Dallas for the Decca label. One of the songs was a version of Tommy Dorsey’s “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You.” The band had been playing a lot of dance music for white audiences and that’s evident when you hear Joe Coleman singing “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You”.

“At first it sounds like pretty standard big band stuff,” says Haddix. “Then after a kind of schmaltzy vocal, Bird jumps in and takes wing. He’s playing bebop here in Kansas City, 16th notes going to double time, all the tricks of the trade are on full display. It’s such a contrast (to the rest of the song) with Bird playing this otherworldly kind of Bebop before anybody knew what Bebop was. It’s just a revelation!”

While the recordings show Parker’s playing style practically fully formed, it had of course come after several years. Parker was playing during the golden age of Kansas City jazz throughout the 1930s – it was an era that presented as many obstacles as opportunities. There was for instance, a now-famous humiliation at the Reno Club from drummer Joe Jones, who ushered a faltering Parker off stage by throwing a cymbal at his feet.

Later that year, Bird traveled to Musser’s Tavern, a resort that staged concerts at Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri. On the journey, Bird was in a car wreck that saw bassist George Wilkerson killed, and left Parker laid up with a broken back, cracked ribs, and a busted horn. While the silver lining was a new Reno saxophone from Mr Musser, who was a very generous and eccentric individual, the doctors prescribed Parker heroin for his recuperation, and afterwards he suffered from a life-long addiction to narcotics.

But showing typical resilience and determination, Parker made the trip to Musser’s Tavern again the following year, “to play a gig with George E. Lee,” Haddix reveals. “Bird spent the rest of the summer there, where he was able to woodshed all summer long, and by all accounts when he came back, he was musically a transformed musician. And that’s when he starts experimenting with the changes that would lead to bebop.”

During these years, Parker was also playing with saxophonist and long-time mentor Buster Smith at Lucille’s Paradise on 18th Street in Kansas City. And it was just around the corner, at the Musicians Union Local 627, that Dizzy Gillespie first met Parker and listened to him and Step-Buddy Anderson playing proto-Bebop in 1940.

But while Kansas City was his home, Parker had mixed feelings about the city, in particular its segregation. Bird played with both black and white musicians in his band, at a time when it was considered not just unconventional, but even dangerous. He had to keep his wits about him.

“Well, when you’re an African American musician in America in the 1930s, you have to improvise to survive,” explains Haddix. “For example, when they were out on the road, most of the time they’d stay in people’s homes, because no hotel would take them in during segregation. They faced racial discrimination at every turn, as well as the hostility of the local police, the strange African American in small towns. So he had to improvise, and that kind of comes through in his music, making leaps as he went along. He found beauty in that, but ugliness too”.

Bird was traveling with pianist and bandleader Jay McShann, when in Natchez, Mississippi, he and singer Walter Brown were arrested for smoking cigarettes on the front porch of a home where they were staying. The police beat them so viciously that Gene Ramey, the renowned bassist, said “you could hang a hat on the knots on their heads”.

“And what did Bird do?” asks Haddix. “He wrote a song about it called “What Price Love”, which later became “Yardbird Suite”. One of the most beautiful compositions of all time came out of that horrific experience.”

One of the last recordings on the collection is a version of Bird’s signature song “Cherokee” at a late night session at Phil Baxter’s house in 1951. Phil Baxter was an interesting figure in Kansas City lore, a barber by trade who was one of the Midwest’s biggest pot dealers, who would throw late-night jam sessions and racially-mixed parties at his house on the east side. When Bird was in town, he’d go over to Phil’s house and jam, and was considered as one of the Baxter family. Bird had returned to Kansas City after losing his cabaret card, playing out of Tootie’s Mayfair and regularly stopping by Baxter’s. On this occasion, a modern wire recorder was set up, which was a precursor to open reel tape technology. This afforded much more recording time in comparison to the lacquers of the 1940s.

“The problem with the lacquers is they can only hold three minutes of information on each side,” Haddix points out. “So, Bird’s restricted to three minutes to tell his story, and that’s very limiting and it gives an incomplete portrait of what could happen. But with the technical breakthrough of wire recording, it captures Bird really stretching out for the first time during that era.”

In many ways, “Bird In Kansas City” captures the odyssey of Charlie Parker’s life, through the lens of his hometown. It’s possible to compare recordings before and after the genesis of Bebop, which reveals his remarkable development as an improviser and a musician.

“But it also gives us an insight into his relationship with Kansas City, musically and socially,” Haddix concludes. “It starts with him on his way out of town with the Jay McShann band, as they were just about to record “Hootie Blues” and have a big hit with “Confessin the Blues” and then leave town in the fall of 1941. But then it also chronicles his return in 1951, just a few short years before his passing.”

Max Cole is a writer and music enthusiast based in Düsseldorf, who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

Header image: Charlie Parker. Photo courtesy of the Driggs Collection, Jazz at Lincoln Center.