In his 1950s heyday, Chet Baker was both heartthrob and hero, venerated for his talents as a trumpeter and singer, and an innovator of cool jazz known as ‘The Prince of Cool.’ But he took a hard road. Drug addiction and jail time helped to seal his notoriety, while contributing to his all-too-early downfall. Here, we trace his tragic life and career through key recordings.

At the beginning of 1950s, while still in his early 20s, Baker emerged as a rising talent of West Coast jazz, playing with Stan Getz and accompanying a visiting Charlie Parker. In 1952, he joined the quartet led by baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, helping to establish the group as one of the leading purveyors of cool jazz, turning away from the blazing virtuosity of be-bop in favour of a more mellow and relaxed sound. Baker and Mulligan were the perfect pairing, avoiding the unison melody lines of be-bop and instead intuitively complementing each other with unexpected counterpoint. “Lee Konitz Plays With The Gerry Mulligan Quartet,” captures the group in early 1953, joined by alto saxophonist Konitz, another cool jazz star, on a date that swings and smoulders.

Lee Konitz and Gerry Mulligan Lee Konitz Plays With The Gerry Mulligan Quartet (Blue Note Tone Poet Series) LP

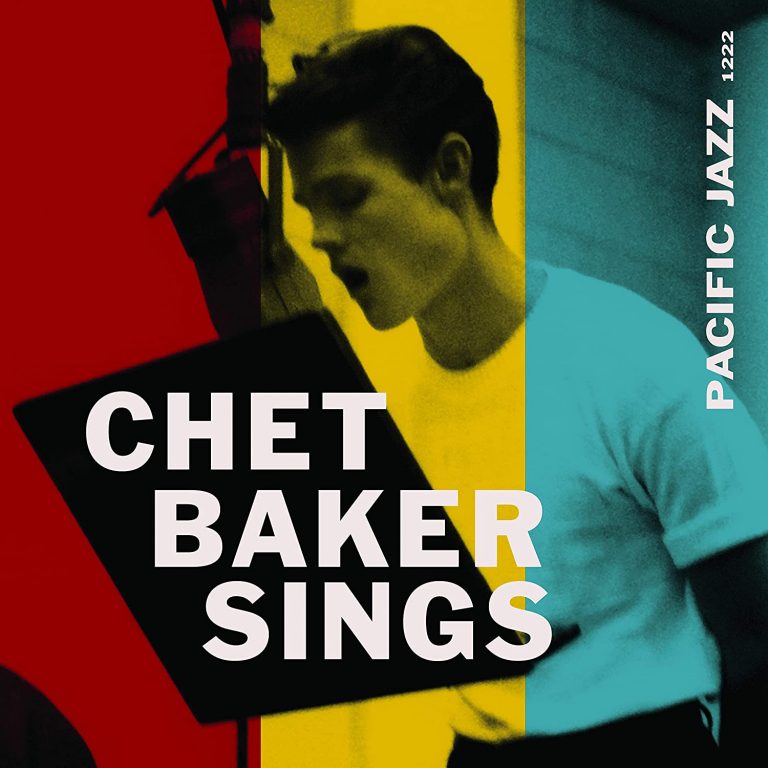

Available to purchase from our US store.Baker’s tenure in Mulligan’s band ended abruptly in mid-1953 when he served six months in prison on a narcotics charge. On his release, he took a surprising new direction, recording “Chet Baker Sings” in 1954 and launching himself as a vocalist with a light and languorous voice that was shockingly androgynous for the day. The album was a major success and – together with his matinee-idol image – catapulted Baker to pin-up stardom on a par with James Dean. It remains a delight, with Baker’s seductive interpretations of popular standards setting a standard for louche insouciance. Dripping with aching longing, Baker’s reading of “My Funny Valentine” was a big hit and became his signature tune.

CHET BAKER Chet Baker Sings

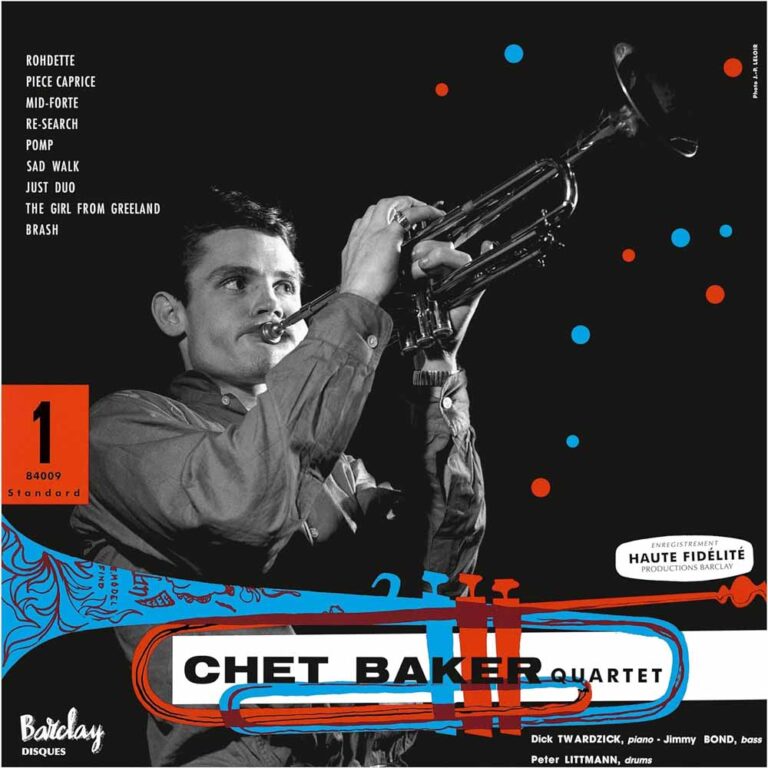

Available to purchase from our US store.Despite his new-found singing fame, Baker remained an important stylist on trumpet. In October 1955, he toured Europe for the first time and, cut a series of studio sessions in France, released in three volumes as “Chet Baker in Paris.”

Chet Baker Quartet In Paris Vol. 1 LP

Available to purchase from our US store.Volume 1 features his quartet, with Dick Twardzik on piano, Jimmy Bond on bass, and Peter Littlemann on drums, romping through eight tunes by composer and arranger Bob Zieff and one by Twardzik. There’s an effervescence and joie de vivre to the set, with Baker showing he was quite at home in more up-tempo numbers.

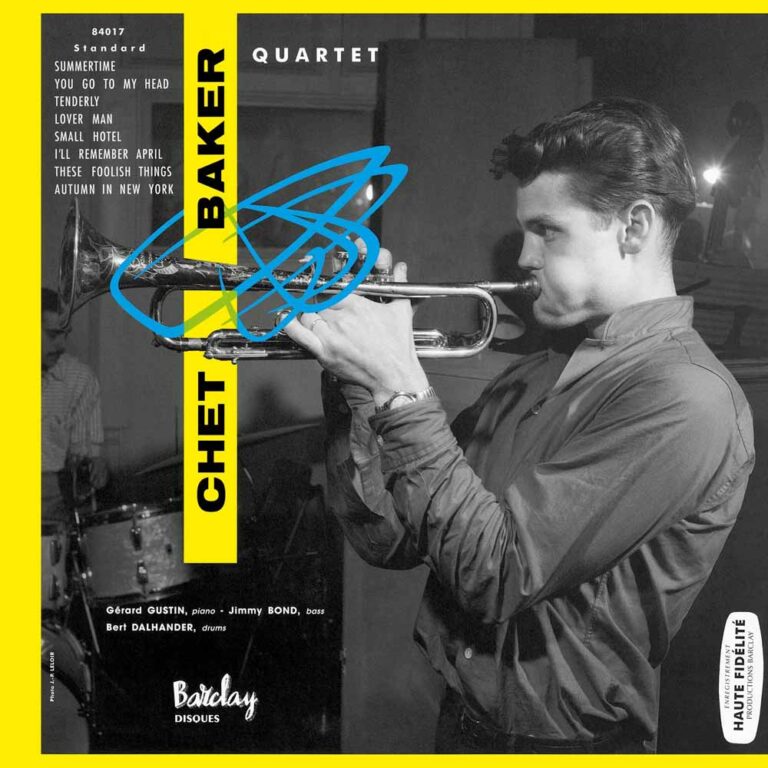

Chet Baker Quartet In Paris Vol.2 LP

Available to purchase from our US store.On Volume 2, Jimmy Bond is the only member of the original accompanying trio present, joined by Swedish drummer Nils-Bertil Dahlander and French pianist Gérard Gustin replacing Twardzik, who had died of a heroin overdose, aged 24, just three days before the session. Here, the quartet tackles eight standards, ranging from the languid ballad “Tenderly,” to a mid-tempo “Summertime.” Baker’s phrasing is impeccably economical and succinct, and infused with a palpable melancholy.

Volume 3 collates a few different recording sessions, including one as a quintet featuring Belgian saxophonist Bobby Jaspar, with Baker shining both on poised ballads and more swinging numbers that lean towards hard bop.

Chet Baker And His Quintet With Bobby Jaspar In Paris Vol. 3 LP

Available to purchase from our US store.Though Baker’s drug consumption and brushes with the law continued throughout the rest of the 50s, he was still able to make some major recordings. Recorded December 1958 and January 1959, “Chet” – aka “The Lyrical Trumpet of Chet Baker” – is an impressive date featuring an all-star cast including flautist Herbie Mann, guitarist Kenny Burrell, pianist Bill Evans and the rhythm section of bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones – at that time working for Miles Davis.

Chet Baker Chet 1LP

Available to purchase from our US store.The credentials of his collaborators are testament to Baker’s chops. While he was a well-known singer by this point, on this masterly instrumental album he imbues nine standard ballads with laconic charm. But Baker’s lifestyle started to catch up with him. From 1960, he spent nearly a year and a half in an Italian prison for various drug offences, after which fresh arrests saw him bounced between Switzerland, France, England and West Germany before finally being deported to the US and winding up in New York in 1964. Yet, somehow, his talent remained undiminished.

Recorded in 1965, “Baker’s Holiday” is a tribute to Billie Holiday, with Baker – now playing flugelhorn – backed by a larger group including pianist Hank Jones. Across 10 tunes associated with Lady Day, on four of which Baker sings, his timing and tone are exquisite.

Chet Baker Baker’s Holiday LP (Verve Acoustic Sounds Series)

Available to purchase from our US store.The following year, in 1966, everything changed. Baker was severely beaten – most likely during a drug deal gone bad – and several of his teeth were knocked out, wrecking his embouchure so that he had to relearn how to play the horn. Signalling a turn into pop and easy listening, 1970’s “Blood, Chet And Tears”, is a moving snapshot of the struggles he faced.

Chet Baker Blood, Chet And Tears LP (Verve By Request Series)

Available to purchase from our US store.On tunes like “Come Saturday Morning” and The Beatles’ “Something” his voice drips with emotion – sweetly vulnerable yet defiantly assured – revealing an artist tortured by his own circumstances. Yet even this wasn’t the end of Chet Baker. In 1973, after several years out of the public eye, he launched a comeback, returning to his jazz roots and beginning a period of prolific recording. Throughout the 70s, he gained a reputation for spellbinding live performances, increasingly favouring the hush of an ensemble without drums.

Then, in 1983, he contributed a trumpet solo to Elvis Costello’s song “Shipbuilding,” bringing his ineffable talent to a new generation of fans. It was a final flush of fame. In 1988, Baker fell to his death from a second-storey hotel window in Amsterdam, aged 58. Heroin and cocaine were found in his system. It was a sad end to one of the most turbulent lives in jazz. Yet his timeless talent and charisma live on.

Read on…Blossom Dearie – The Maverick with the Soft Voice

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Chet Baker performs in a nightclub circa 1952 in New York City, New York. Photo: PoPsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.