The record my friend showed me was “Out to Lunch!”, the avant-garde masterpiece by jazz saxophonist, clarinettist and flautist Eric Dolphy. The most tragic fact about this album is that its creator wouldn’t even live to see its release date. He had recorded the music in February 1964, but died in June, at the young age of 36, two months before the album release, two days after collapsing on stage in a Berlin jazz club.

Critics have been hesitant to state the obvious, but Dolphy’s contribution to jazz cannot be overemphasised, and “Out to Lunch!” is a snapshot of an outstanding musician in his absolute prime, playing with a band that trusted him blindly to go anywhere he wanted to, whether that meant nodding to Monk’s mystical chord voicings (“Hat and Beard”) or referencing an Italian classical flautist (“Gazzelloni”). Oscillating between genres, Dolphy’s music matched the very definition of “third stream” at that point.

That term had been coined by composer Gunther Schuller to describe music that falls halfway between jazz and classical. On the second half of his “Jazz Abstractions”, released in 1961, Dolphy played bass clarinet. This notoriously difficult instrument had not been played like that before – it was a staple of classical performances, but rather unpopular in jazz. Dolphy conjured sounds from it that no one had ever heard. In fact, he employed every instrument, whether the saxophone, the flute or the clarinet, in a radically expressive form.

Dolphy loved bop, but he was also very much into modern composers like Webern, Berg, Débussy, Bartók, and Messiaen. Growing up in Los Angeles studying saxophone and clarinet from age six, he originally aspired to get a job in a symphonic orchestra. After joining a jazz group in college, he moved to New York in the late 1950s, starting to work with Chico Hamilton and then Charles Mingus. In 1960, he played in the second quartet of Ornette Coleman’s genre-defining album “Free Jazz”.

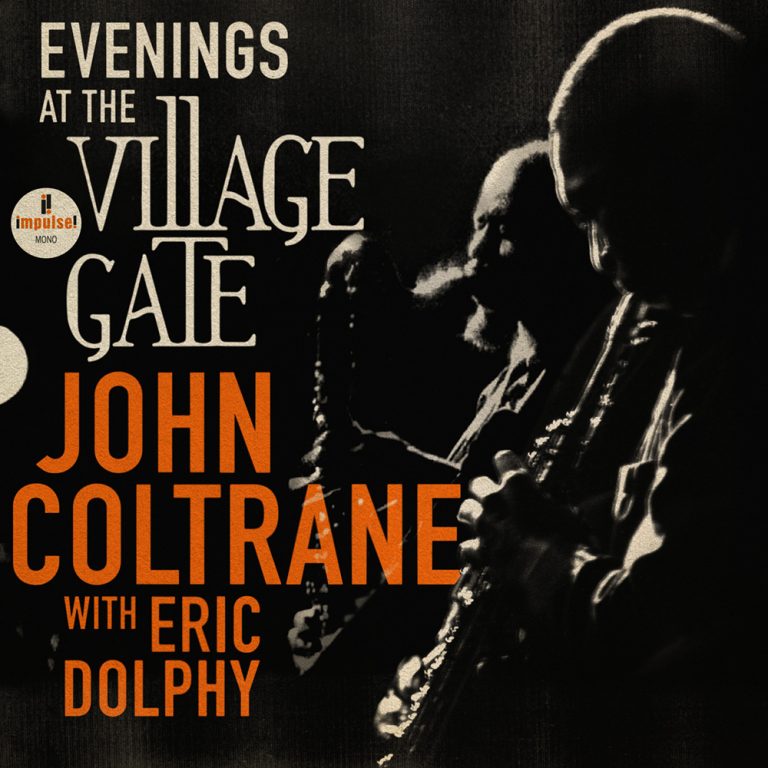

Dolphy had known John Coltrane for some years by then, and they would exchange bold musical ideas as Trane started moving away from hard bop. When Dolphy showed up on 1961’s “Africa/Brass”, they immediately created one of the high points of that era’s musical avant-garde (which critics then dismissed as ‘anti-jazz’). They also played nightly at New York’s Village Gate that year; some recordings from those concerts were just released.

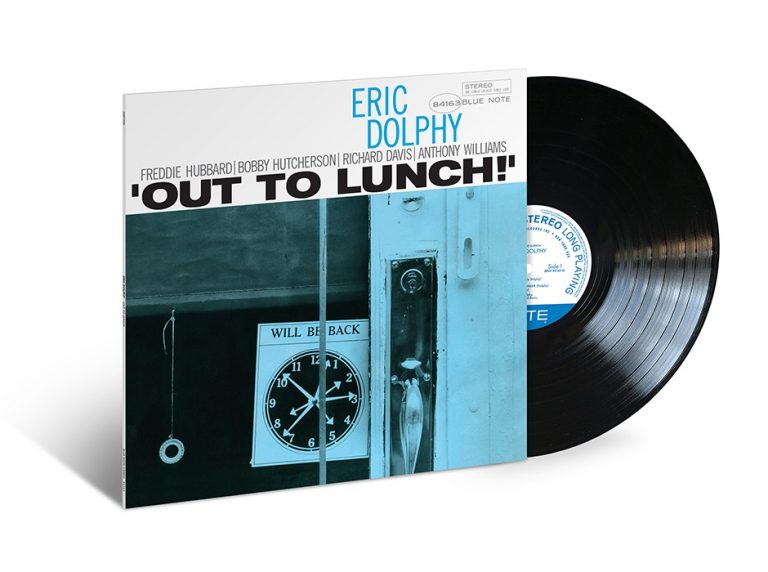

Fast forward three extremely productive years, and Dolphy had signed to Blue Note to record an album with a new band: Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Bobby Hutcherson on vibraphone, Richard Davis on bass, and a young Tony Williams on drums. “Everyone’s a leader in this session”, Dolphy wrote in the original liner notes. Compared to Ornette Coleman’s free jazz, the five original tracks on “Out to Lunch!” bore a rather traditional compositional foundation. It seemed as if Dolphy was ready to move on – in this case, to Europe.

Even today, like for me back in the 1990s, discovering “Out to Lunch!” can be a life-changing moment. This record encapsulates everything that’s exciting about jazz – the revolutionary spirit of freedom within a structural framework steeped in blues tradition. To quote Gunther Schuller, this is not just “jazz with strings”, or “jazz in fugal form”, or “inserting a bit of Ravel or Schoenberg between bebop changes”. Instead, Dolphy and his band created an experimental, rhythmically complex chamber jazz, predating the founding of ECM by half a decade.

When the show promoter came to get Dolphy for his last gig in Berlin, the musician lay on the hotel bed sweating and devouring ice cream. Though he seemed sick, he didn’t want to see a doctor. Collapsing on stage, he got rushed into a hospital. Rumours of a drug overdose circulated immediately. Which couldn’t have been farther from the truth: Dolphy was a teetotaler – but also an undiagnosed diabetic. Unknowingly to himself and the doctors, he’d suffered a diabetic coma. When they finally gave him insulin, it was already too late.

Stephan Kunze is a Berlin-based culture journalist who has been writing about music for magazines and newspapers since 2001. He’s a former Senior Music Editor and Global Editorial Lead at Spotify.

Header Image: Francis Wolff/Blue Note Records