Discover their picks and read their reviews below and, if you’re shopping, you can find all the EJ Albums of the Year on store here.

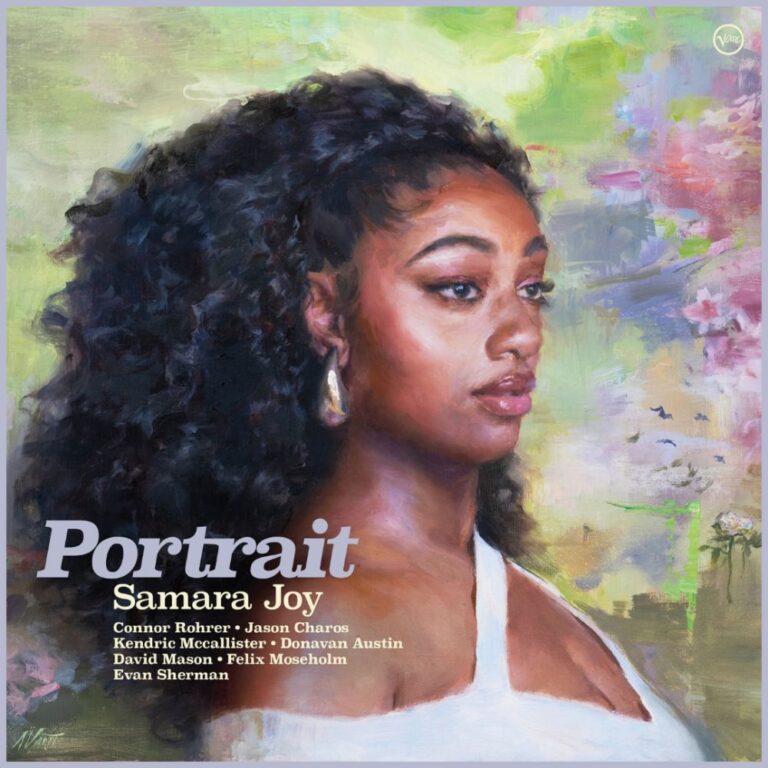

Jumoké Fashola: Samara Joy – “Portrait” (Verve)

The acappella opening of Samara Joy’s reworking of the Charles Mingus tune “Reincarnation of a Lovebird” on her latest album, “Portrait”, has captivated me since the moment I first heard it. The soaring lilt, the expressiveness of her voice, and the quiet confidence of a singer completely in control of her instrument and willing to take on new challenges are all beautifully showcased on this album. It is just one of the standout tracks of the album.

Every artist faces questions when releasing a new record. Will it be good enough? Will it receive the same acclaim as my previous works? Will it endure the scrutiny of peers, critics and audiences? Moreover, how can I continue to grow as an artist without falling into a rut or losing my creative vision amidst the demands of the industry?

It’s important to note that Samara is still in her early twenties, is in demand as a performer, and has already won numerous Grammys, including the coveted Best New Artist Award in 2023. She could have felt overwhelmed by all the accolades, so I’m impressed by how she has embraced these challenges and expanded her horizons, leaving her unique mark on the album.

“Portrait”, recorded at the legendary Van Gelder studio in New Jersey over three days with just two or three takes of each tune, illustrates Samara’s growth as a vocalist while still paying homage to the traditions that inspired her. It also reflects her broader musical influences, including her roots in gospel and R&B. Though she is often compared to greats like Sarah Vaughan, Carmen McRae and Betty Carter, what shines through is the distinct voice of an artist who understands her capabilities and is willing to take risks, even if her core audience – Generation Z – might not fully appreciate it at first.

This is why “Portrait” is the album I am most excited about this year. It has the potential to become a future classic, one that vocalists will study for years to come. It encourages young artists to embrace bravery and freedom in their creative choices, unencumbered by commercial constraints, and to experiment and play.

Samara Joy has a bright future ahead of her. “Portrait” provides a glimpse into what she may achieve next. This is the album that, in years to come, people will reminisce about with the phrase, “I remember when…”

Don’t wait for the future – experience it now!

Jumoké Fashola is a journalist, broadcaster, and vocalist who currently presents a range of Arts and culture programmes on BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4, and BBC London.

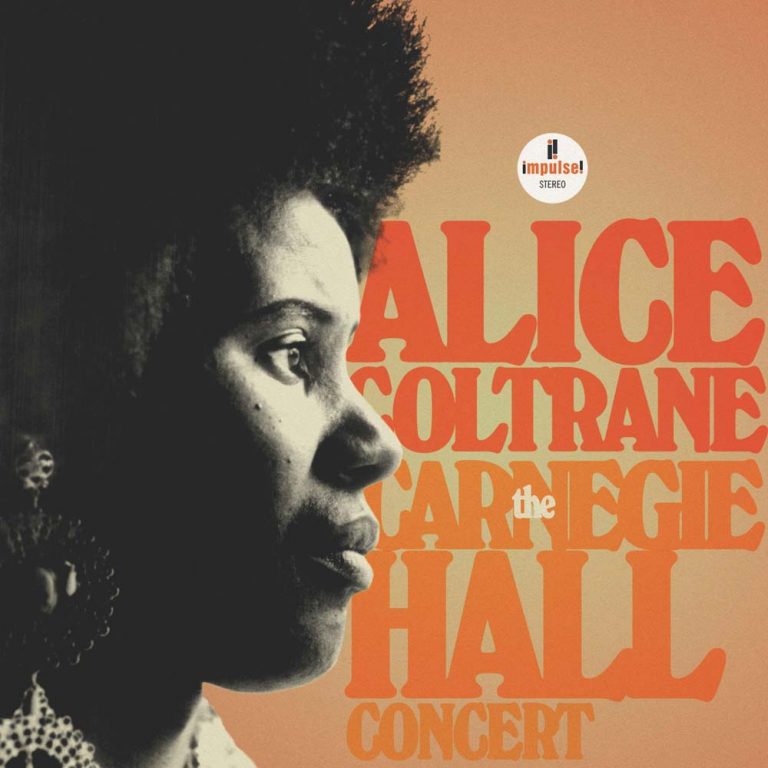

Max Cole: Alice Coltrane – “The Carnegie Hall Concert” (Impulse!)

As a teen, I vividly remember seeing for the first time the cover of John Coltrane’s “Live at the Village Vanguard Again!” Trane’s New Thing quintet stands at the entrance of the esteemed venue, looking like a collection of higher souls, so authentic and out there, and yet so casual with it. I remember thinking: “Who are these beings?” Alice Coltrane stands in the middle, radiating a calm center, anchoring the photo rather like her piano often does that evening. Some years later, a dear friend stayed at the Shanti Anantam Ashram and returned with a clutch of self-released CDs of Alice Coltrane’s (by then known as Turiyasangitananda) devotional Hindu music. I was captivated.

I’d heard of this historic recording in bootleg form, but with this release fans of Alice Coltrane’s music finally had the chance to immerse themselves in the full concert. That evening in 1971, Alice Coltrane’s group was part of a wider programme for that evening’s fundraiser for Swami Satchidananda’s Integral Yoga Institute, alongside singer songwriter Laura Nyro and soul beat combo The Rascals. But the jazz line-up that joined Alice Coltrane on stage pulled no punches because of their pop-leaning co-performers, and featured some of the greatest free players of the era. Pharoah Sanders combined with Archie Shepp on reeds, bassists Jimmy Garrison and Cecil McBee teamed up with drummers Ed Blackwell and Clifford Jarvis, completing an ensemble that also featured a tambura and harmonium players.

The concert starts with a beautiful rendition of “Journey In Satchidananda” featuring Sanders on flute, which brings a distinctly floaty feel in comparison to the album version. There’s a palpable electricity in the air, or a sense of occasion that seems different to the studio recordings of the set list here. The songs are balanced between blissful meditations and blistering sheets of sound, so that the concert crescendos in such a way as to facilitate personal celestial navigation. While Alice Coltrane’s songs “Journey In Satchidananda” and “Shiva-Loka” afford ample foundation for consciousness expansion, versions of John Coltrane’s compositions “Africa” and “Leo” provide the foil for fiery, exploratory improvisations, as the group strikes the perfect balance between universal communion and free jazz revelation.

I’d always thought of Alice Coltrane’s music as being like the ocean, emphasizing as it often does a certain soothing bobbing pulse, that was capable of becoming a stormy squall at a moment’s notice. But after reading Alice Coltrane’s accounts of levitation and astral projection in her book “Monument Eternal”, these naturalistic metaphors seem inadequate, bound as they are by the forces of gravity. Alice Coltrane is simply on an astral plane all of her own.

Max Cole is a writer and music enthusiast based in Düsseldorf, who has written for record labels and magazines such as Straight No Chaser, Kindred Spirits, Rush Hour, South of North, International Feel and the Red Bull Music Academy.

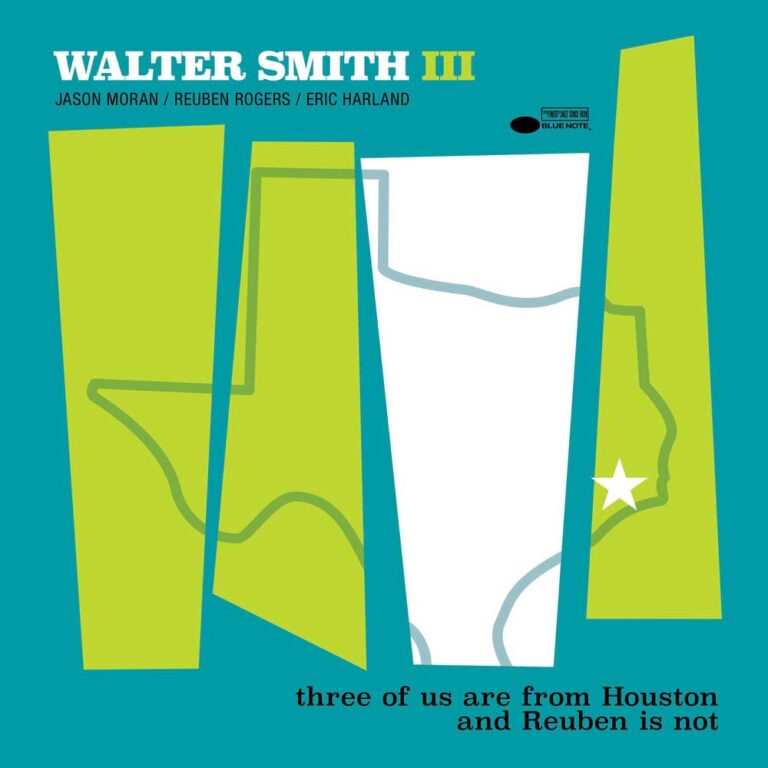

Kevin Le Gendre: Walter Smith III – “Three Of Us Are From Houston And Reuben Is Not” (Blue Note)

Humour is not largely synonymous with jazz these days, but that doesn’t mean it is entirely absent or reducible to the lol code. This work by Walter Smith III, a fitting follow-up to last year’s excellent “Return To Casual”, finds the saxophonist-composer exercising an off-kilter wit and salty provocation that may well draw a knowing grin of recognition from those who appreciate the forced smile discomforts of modern life.

“Office Party Music” is a fabulous smirk in sound. It is as downbeat and melancholic as end of year company gatherings really can be, offering food for thought on what might not be said between colleagues either in person or online, as if remote working is making us all more emotionally distant. Smith’s tenor is majestic in any case, gliding over the relaxed pulse with a tone that, though flint solid, easily tips into sensitivity through a drop of volume or burst of breathiness, while pianist Jason Moran, drummer Eric Harland and double bassist Reuben Rogers are soulfully discreet yet impactful as the song builds to a flickering coda.

Since his 2006 debut “Casually Introducing” Smith has been plotting his own personal path through contemporary improvised music that is as pleasingly resistant to categorization as that of peers as well as predecessors such as Moran and Harland, who, as implied by the album title, share a proud Texan heritage unlike odd man out Rogers. He hails from the Virgin Islands and has carved an enviable reputation on the US scene through outstanding work with Smith, Charles Lloyd and Dianne Reeves, among many others.

Although Smith has led several fine bands to date, this ensemble could be his own “classic quartet” in the horn-acoustic rhythm section historical model that counts such as Gordon, Coltrane, Rollins, Ervin and Marsalis. First and foremost the band has reached that four-in-one-one-from-four togetherness that produces beauty other than through solos, as ear-catching as they are. The moments of simultaneous improvising, whereby rhythms overlap or snake in and out of one another are effective, above all when Moran’s scurrying right hand and Harland’s pattering snare become a kind of unified percussive voice full of momentum that often rises from low or mid-tempo.

Smith has found his own way of creating energy without necessarily cranking up the afterburners, although he does catch fire on occasion through whirling, winding sixteenth note runs that are attacked with real vigour. Yet on “Gangsterism On Moranish” Smith is coolly plaintive, if not weary, slurring and sliding his phrases into life on the stop–start intro before the groove kicks in and the melody leans cunningly towards the glowing gospel-soul yearnings of Stevie Wonder or Donny Hathaway.

Harland’s backbeat, teasingly resonant, is perfect for the gentle rocking. With Rogers adding ballast to the low end the vehicle has a thickness that hip-hop audiences might welcome but its ambience stems largely from a 2000s sound Moran himself was developing on his series of pieces penned under the umbrella of “Gangsterism On” (Canvas; River; Irons; Lunchtable et cetera). The references are as meaningful as the music, and “Three Of Us Are From Houston And Reuben Is Not” is saying something literal that also has a figurative message about creativity as a meeting place for those who are from a big ole state with Stetsons and those from a string of islands far further south.

Kevin Le Gendre is a journalist and broadcaster with a special interest in Black music. He contributes to Jazzwise, The Guardian and BBC Radio 3. His latest book is “Hear My Train A Comin’: The Songs Of JImi Hendrix”.

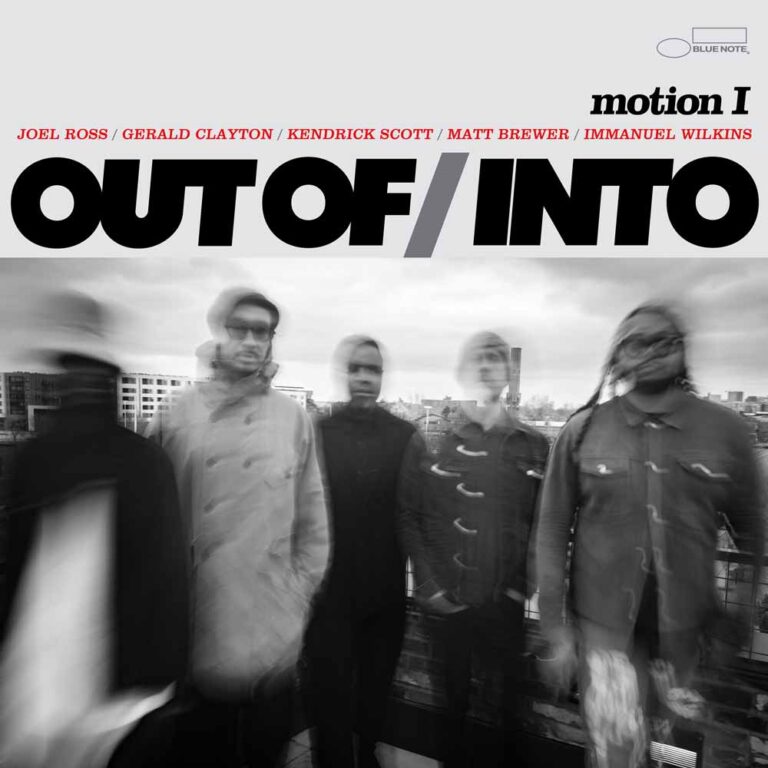

Sharonne Cohen: Out Of/Into “Motion I” (Blue Note)

The legendary Blue Note record label holds a special place for me, as I imagine it does for many other music lovers. The iconic artists, the signature design, look and feel of the albums, the legacy of coalescing tradition and trailblazing innovation.

Honoring the past while looking to the future, Blue Note’s mission for the past 85 years has been to elevate the rising stars of jazz and the music they create. This rich heritage carries on with a new all-star collective and its first recording, released late in the year. “Motion I” showcases complex, intriguing and simply beautiful compositions by its five gifted members: pianist Gerald Clayton, alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Joel Ross, drummer Kendrick Scott, and bassist Matt Brewer.

In the spirit of Blue Note’s longstanding tradition of putting together all-star bands of extraordinary talent through the ages, these are five of the most prominent and impactful voices of their generation, continuing the label’s arc of superior musicianship and continuous exploration. The band’s name alludes to this notion of reverence for the masterful voices of the past, while maintaining continuous movement into the open expanse of the future. “Out Of/Into reflects the evolution of the Blue Note story, and of our sound,” says Scott.

The collective was first conceived as the Blue Note Quintet in early 2024, in celebration of the label’s 85th anniversary. Throughout an extensive tour, the band recorded this debut album. Alluding to its exploratory energy, Wilkins explains how “with such a long time on the road, it was really nice to reach as far as possible”, while Clayton comments on how the artists “pushed one another to reach further and dig deeper night after night.” With a group as exceptional as this, it’s easy to understand how over the course of two months, the music “expanded in all directions,” things growing “both tighter and looser.”

The inspired set presents seven original works by the band members, all brilliant conduits for improvisation explored throughout nearly 40 live shows. These artists’ paths have intertwined over the years on recordings and stages, giving rise to the group’s synergy and deep listening, palpable and profoundly engaging. As the album unfolds, individual soloists follow the collective’s powerful, propulsive energy to magnificent altitudes; at times, the entire ensemble soars. Post-bop is punctuated with aspects of avant-garde, conjuring some of the most captivating Blue Note albums of the 1960s (McCoy Tyner, Bobby Hutcherson, Wayne Shorter, Eric Dolphy et cetera), while clearly representing music of the here and now.

Reaching down, and out, while also honoring Blue Note’s rich history, the way the collective keeps the label’s legacy going is, as Ross puts it, “by unapologetically being true to ourselves” – with abounding creativity, and a sense of intrepid, daring exploration.

In this age of single-file downloads, there’s something about this album that reminds me of the cherished experience of sitting down with a new album, unpacking it, and listening to it from start to finish – an immersive continuum of music.

Sharonne Cohen is a Montreal-based writer, editor and photographer for music, arts and culture, with bylines in DownBeat, JazzTimes, Okayplayer, VICE/Noisey, Afropop Worldwide, The Revivalist, and La Scena Musicale.

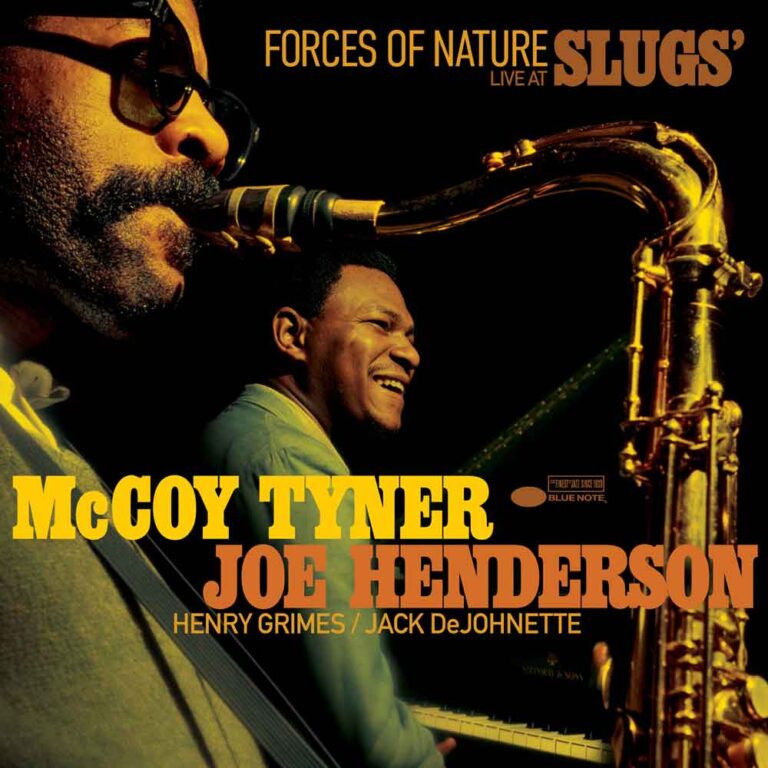

Dan Spicer: McCoy Tyner & Joe Henderson “Forces Of Nature: Live at Slugs’” (Blue Note)

Just when I thought I had my best of 2024 lists all worked out, along came this extraordinary banger at the end of November and blew everything up. “Forces of Nature: Live at Slugs’” is one of those rare, never-before-heard archival finds that simply rewrites the jazz history books. Recorded in 1966 at the legendary eponymous jazz club in New York’s East Village, it features a band that never made a studio recording and probably only played a handful of gigs together.

But what a band. This incredible unit was co-led by two of the most powerful and inventive instrumentalists of all time: pianist McCoy Tyner and tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson. Each had already climbed to the top-tier of jazz by this point, both as sidemen – Tyner with John Coltrane’s Classic Quartet, and Henderson with Horace Silver’s influential hard bop band – and as leaders on their own recording dates.

They’d also worked together, with Tyner appearing on three of Henderson’s seminal, early-1960s Blue Note dates. For the session at Slugs’ these heavyweights were joined by two firebrands. On bass was Henry Grimes, a serious talent who had cut his teeth playing straight-ahead jazz with Sonny Rollins and others before becoming a doyen of the avant-garde and working with the likes of Albert Ayler and Don Cherry. Rounding out the quartet was Jack DeJohnette, still only 23 and a few years from his tenure in one of Miles Davis’s most adventurous line-ups.

Together, they create a sound and energy that are both firmly grounded in tradition and at the same time audibly straining to break free and soar to unimaginable new heights. There’s a deeply swinging, mid-tempo romp through Henderson’s “Isotope” from his album “Inner Urge”, recorded 1964 and released just a few months before this live date. There’s a gloriously fleet-footed version of Tyner’s waltz, “The Believer,” which John Coltrane had recorded in 1958, a couple of years before Tyner joined his band. And there’s the achingly beautiful standard ballad “We’ll Be Together Again.”

But for me, the main attraction is the two lengthy tracks that dominate the album: a nearly-27-minute blast of Henderson’s “In ‘N’ Out” (the title track from his 1965 album, on which Tyner played), and a blazing 28-minute group composition suitably entitled “Taking Off.” On both of these, the tempo is through the roof, as each musician pushes the limits of stamina and endurance to the very limit. Grimes lays down furiously fast walking bass lines. DeJohnette thrashes and crashes, keeping propulsive time accented by enormous surges of power that nod to the muscular innovations of Tyner’s old band mate, Elvin Jones. And the two leaders take long, exploratory solos that overflow with ideas, unflagging in their invention and gripping in their commitment. It’s revolutionary, dangerous and exciting. It’s the sound of pure jazz. And we’re so lucky to finally be able to hear it.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Jane Cornwell: Arooj Aftab “Night Reign” (Verve)

Back in 2021, Arooj Aftab’s “Mohabbat” hit me like a thunderbolt. Released as the world emerged, blinking, from lockdown, it was ethereal but visceral, powerful but delicate, driven by a note-perfect voice that seemed to journey through its four movements with nuanced flair and a sort of intergalactic might. It felt hopeful, soothing and fiercely defiant.

‘Seeing how you have ample lovers around you, I will not be one of those lovers to you,’ intoned Aftab in Urdu, lyrics that – though written in the 1920s by esteemed poet Hafeez Hoshiarpuri – hinted at a rebellious aesthetic. The song won the 2022 Grammy for Best Global Music Performance, and with her 2021 album “Vulture Prince”, a work informed by grief and strafed with contrast, saw Aftab nominated for Best New Artist. “With this nomination I don’t feel otherised anymore,” she said.

I would go on to speak to the whip smart New Yorker for publications in Australia and the UK, and – around the release of her current, glorious album “Night Reign” – for Everything Jazz. Each conversation found the Berklee graduate and fixture of New York’s jazz and experimental music scenes reiterating her determination to push back at glib categorisations of her music. For while Aftab grew up in Lahore, absorbing South Asian classical forms of music and poetry, she had the likes of Billie, Ella, Frank and Miles on rotation. She loved punk and rock, Leonard Cohen and Terry Riley.

Aftab folded such myriad influences into a singular oeuvre. “There was no blueprint for the thing I wanted to do,” she told me. Risk-taking is vital: she flexed her improv chops with fellow NYC adventurers, pianist/composer Vijay Iyer and bassist/multi-instrumentalist Shahzad Ismaily, on their 2023 album “Love in Exile”, adding another dimension to a sound that speaks to multiple roots and heritages, finding its identity in movement and change. And now, in the night.

“Night Reign” is a tradition-defying collection of nocturnal-themed tracks that evoke parties until 6am, conversations across time differences and whisky bottles drunk down to their last dregs. It’s a project involving band members including harpist Maeve Gilchrist and guitarist Gyan Riley – Terry Riley’s son – alongside leftfield A-listers such as Moor Mother, Chocolate Genius, vibraphonist Joel Ross and Iyer/Ismaily; a recording that embraces the freedom in creative gambles while benefiting from Aftab’s compositional nouse, her knack for penning arrangements playful and questing.

Highlights are many: the rocking “Bolo Na”. Lead single “Raat Ki Rani”, a tune about an alluring stranger at a garden party sung in a voice – because, why not – that’s been ever-so-slightly autotuned. “No Gui” imagines a conversation between two badass women of history, 18th century Urdu musician/courtesan Malaika Chai Banda and 16th century warrior queen Chand Bibi, defeater of Mughal armies; “Whisky” is raw, wry, imbued with Aftab’s default sense of yearning and longing. “I’m ready to let you fall in love with me,” she sings.

Which is ironic, since I’d fallen years ago. But with “Night Reign”, I fell harder.

Jane Cornwell is an Australian-born, London-based writer on arts, travel and music for publications and platforms in the UK and Australia, including Songlines and Jazzwise. She’s the former jazz critic of the London Evening Standard.

Les Back: Meshell Ndegeocello “No More Water: The Gospel of James Baldwin” (Blue Note)

“It’s now December and the world has lost its fucking mind”, says Staceyann Chin in a spoken word passage of Meshell Ndegeocello’s album “No More Water: The Gospel of James Baldwin”. The album is a musical homage to Baldwin in the year which marks the centenary of his birth. His book “Fire Next Time” was published in 1963 and took its title from the African-American spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep”:

God gave Noah the rainbow sign

No more water, the fire next time

Ndegeocello’s album takes the first part of the couplet as her title. It sets Baldwin’s deep insight into the violence of racism in America to music showing its continued relevance to the era of police violence where a black child playing with a toy gun in the street at Christmas can get them killed.

It is my album of the year not as a historical document though but rather for its prophetic qualities. Listening to the album through the winter of 2024 in the political atmosphere of fear and hatred was like hearing a musical forewarning come true, as we watched American democracy “move backwards through history.” The album, in a way, anticipated the power of hate and scaremongering in shaping the political outcome of the 2024 US Presidential election.

The songs summon African-American thinkers like James Baldwin and Audre Lorde in the spirit of contemporary freedom songs. Its musical textures feature an infinite variety of contemporary black music from jazz and Afrobeat to gospel and funk and even a post-Hendrix rock guitar solo. The vocal performances by Justin Hicks on “Travel” and “Eyes” are personal high points. The album also features exquisite harmony singing from Kenita Miller and Meshell Ndegeocello on tracks like “Trouble” which wouldn’t be out of place on a Luther Vandross album. The music carries within it what Yeats called a “terrible beauty”, a rageful truth about the war being visited on the black urban poor in America and the violence of sexism and white supremacy experienced by black women.

This is not easy music to listen to and neither should it be. Nonetheless, it is music that everyone needs to open their ears to. It confronts the violence that racism inflicts on black and brown bodies and the damage it does to white people too. As psychiatrist and anti-colonial philosopher Frantz Fanon commented, racism amputates our shared humanity and replaces it with the masks of race. Those masks are sometimes a defensive shield and sometimes a hateful weapon. As the album’s narrator says: “People cling to hatred to avoid confronting their own wounded selves.” There is no more urgent political message to our time than this.

My favourite track on the album is entitled “Love.” It is inspired by these lines from Baldwin’s “Fire New Time”:

“Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within. I use the word ‘love’ here not merely in the personal sense but as a state of being, or a state of grace – not in the infantile American sense of being made happy but in the tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth.”

Shared humanity is not a point of departure, but rather a destination that remains on a future horizon. Meshell Ndegeocello’s album is a precious musical provocation towards that tough quest for growth and radical love in our world.

Les Back is a sociologist at the University of Glasgow. He has authored books on music, racism, football and culture, and is a guitarist.

Andrew Taylor-Dawson: Nubya Garcia “Odyssey” (Concord)

Having become a leading figure in UK jazz and landing a critical smash with her Mercury Prize nominated debut album “Source”, tenor saxophonist Nubya Garcia had a lot to live up to with “Odyssey”. She didn’t disappoint.

Coming a full four years after her debut, Garcia has worked on numerous projects in between, from the collaborative “London Brew” album that paid tribute to Miles’ “Bitches Brew” to lending her emotive sax work to Nala Sinephro’s records.

Undaunted by the weight of expectation, Garcia took her time to deliver in “Odyssey” a record that sees her develop significantly as a composer, offering huge sonic variety and beautiful emotional range. It is a record that is complex and intriguing, but accessible enough to appeal to both the dyed-in-the-wool jazz fan and the listener dipping a toe into these waters for the first time.

Garcia is backed by her long-standing band comprised of fellow London jazz innovators Joe Armon-Jones on keys, Daniel Casimir on double bass and Sam Jones on drums. The quartet are a tight unit, who bring real creativity and a sense of freedom to Nubya’s wide-ranging compositions.

The strength of the band is demonstrated on the gorgeous “Solstice”, which opens with the detailed and bright piano work of Armon-Jones augmented beautifully by Casimir’s bass and Jones’ tight-shuffling, almost breakbeat-like drums. Garcia’s languid and rich lead sax line slides over the top of the mix, before she delivers one of the record’s most hard-hitting solos.

Throughout “Odyssey”, the compositions are pushed to a new level of emotional impact by the addition of strings, which Garcia, in a major development for her own compositional approach, arranges for the first time. She collaborates across the piece with Chineke!, Europe’s only majority-Black orchestra.

Soulful and affecting vocal turns are put in by guests Esperanza Spalding, Richie and Georgia Anne Muldrow. Garcia herself provides spoken word vocals to the rousing album closer “Triumphance”. Each vocal performance adds to the underlying theme of self-empowerment and overcoming the odds. But given that this is an instrumentally driven record, it is the emotional resonance of the compositions that does much of the heavy lifting. From soulful introspection to transcendent joy, Garcia has truly delivered an album worthy of the title “Odyssey”.

Some great records suit particular times or moods, but with her sophomore release Garcia has created a set of real depth that works for headphones on deep listening, or to soundtrack gatherings of friends and more besides. It’s an album that exemplifies the range and adaptability of the contemporary British jazz scene, cementing Garcia not only as one of its great instrumentalists, but as a composer willing to fuse influences and take risks.

Andrew Taylor-Dawson is an Essex based writer and marketer. His music writing has been featured in UK Jazz News, and Songlines. Outside music, he has written for The Ecologist, The Quietus, Byline Times and more.

Matt Phillips: Immanuel Wilkins “Blues Blood” (Blue Note)

It doesn’t happen much these days, but it’s always a treat when you walk into a record store and get blown away by what’s playing. Entering London’s legendary Ray’s Jazz in Foyles bookshop recently, I was instantly smitten by a sermonising alto sax and harmonically-rich piano accompaniment out of Wayne Shorter, driven along by some unobtrusive yet “funky” drumming. Who was this? Kenny Garrett? Something from the M-Base crew, Greg Osby or Steve Coleman?

The concept album has a long tradition in jazz, and over the last five years Immanuel Wilkins has been busy adding to it. He debuted with 2020’s “Omega”, issued when he was just 22, then made 2022’s “The 7th Hand” during a period when he was also a sideman with Joel Ross, James Francies and Kenny Barron.

And then this year saw the release of “Blues Blood”, based on a multimedia event commissioned by Roulette, a Brooklyn arts venue. Taking inspiration from the story of the Harlem Six – a group of teenagers falsely accused of murder in 1965 and then brutally beaten by prison guards to get confessions – the piece, featuring on-stage cookery too, was originally streamed live on YouTube and is still available to view.

Co-produced by Meshell Ndegeocello, “Blues Blood” is Wilkins’ first album to feature vocals. June McDoom, Yaw Agyeman, Ganavya Doraiswamy and Cecile McLorin Salvant, who guests on three tracks including the moving “Dark Eyes Smile”, do Wilkins’ excellent melodies proud. Like Esperanza Spalding’s recent “Songwrights Apothecary Lab”, this album is a landmark of vocal jazz, taking the genre to places it’s never been. Elsewhere the two instrumentals – “Moshpit” and the title track – are first-rate examples of spiritual jazz.

It’s harmonically ambitious and there’s not a bar of traditional 4/4 swing on “Blues Blood”, yet it still sounds immediately familiar, accessible and welcoming, and packs quite an emotional punch. Anyone who’s enjoyed Ndegeocello, Spalding, Osby, Robert Glasper or Shorter’s post-1970s music should settle right into this. We look forward to the next chapter of Wilkins’ Blue Note career with great excitement.

Matt Phillips is a London-based writer and musician whose work has appeared in Jazzwise, Classic Pop and Record Collector. He’s the author of “John McLaughlin: From Miles & Mahavishnu To The 4th Dimension” and “Level 42: Every Album, Every Song”.

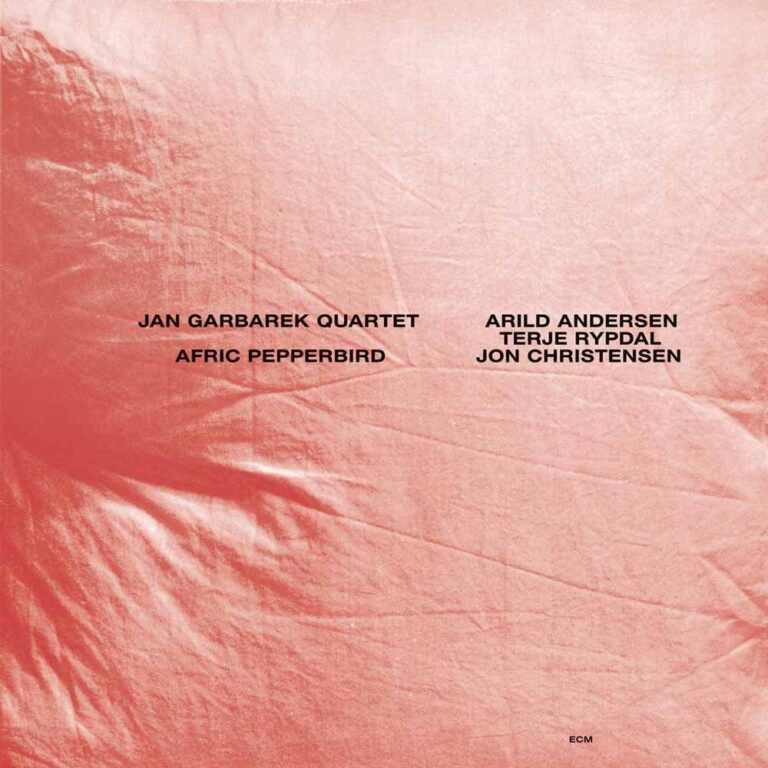

Jon Opstad: Jan Garbarek “Afric Pepperbird” (ECM)

Jan Garbarek’s “Afric Pepperbird” was just the seventh release on the legendary ECM label, and something of a breakthrough for both the Norwegian saxophonist and for the label itself. With the album re-released this year as part of ECM’s high quality Luminessence series of vinyl reissues, I’ve been taking this as a chance to fully appreciate the brilliance of this pivotal recording in the label’s early history, re-listening to it in-depth.

Garbarek’s sound at this early stage in his career draws on the intensity of late John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders and Albert Ayler, but combines this with a particular Nordic lyricism that makes it totally his own. There’s more fire and intensity here than in many later ECM releases but the recording still has all the hallmarks of being very much an “ECM” album.

It is a unique record label, with no other quite like it. In my own record collection, I currently have somewhere around 550 ECM recordings on CD and vinyl, so I have a strong appreciation for the depth of the label’s catalogue of incredible music. Listening to “Afric Pepperbird” in the context of the six albums that preceded it and the decades of releases after it, it’s amazing how much of the groundwork for the label’s future aesthetic was laid in this album. With ECM finding its footing through those earliest recordings, to my ears there is some special magic happening on “Afric Pepperbird” that makes it feel like the first of the label’s releases to really have that particular stamp all over it.

It was also the first ECM album where all of those involved remained closely associated with the label for decades to follow. In addition to Garbarek, who recorded exclusively for ECM after this, the three remaining band members are each thoroughly unique musical individuals in their own right, and each became key players in the label roster: guitarist Terje Rypdal, bassist Arild Andersen and drummer Jon Christensen. Perhaps equally significant was legendary recording engineer Jan Erik Kongshaug, whose engineering contributed so much to the striking clarity of the recording. This was his first recording for ECM and he engineered countless recordings for the label over the decades that followed through to his death in 2019. This was also the first ECM album to be recorded in Norway, a country that would become significant musically in the future of the label, with what has been described at times as a particular “sound of the north” imbuing many of its releases.

There is a great sense of textural exploration on “Afric Pepperbird”. Contrasting the intensity elsewhere, “Concentus” is a brief, beautiful interlude with floating bowed double bass harmonics and Garbarek (unusually) on clarinet. As well as guitar, Rypdal plays bugle at points, providing an extra wind voice to Garbarek’s instruments. The rhythmically driving “Beast of Kommodo” closes with Garbarek on flute, another instrument that he brings a unique voice to, while towards the end of the title track he can be heard on bass saxophone – a rare instrument in music, and one that Garbarek completely stopped playing after the 1970s. The title track itself is one of the highlights of the album, underpinned by some incendiary drumming by Christensen.

Producer and label founder Manfred Eicher has spoken of being proud of what was achieved on “Afric Pepperbird”. Indeed, it was apparently the album that he sent to pianist Keith Jarrett to convince him of the possibilities of recording for the label. Listening to it now, it’s easy to appreciate why.

Jon Opstad is a London-based composer working across film and television, contemporary dance, concert music and album projects. His scores include the Netflix hits “Bodies” and “Black Mirror”, and Elisabeth Moss thriller “The Veil”, co-composed with Max Richter.

Freya Hellier: Ethan Iverson “Technically Acceptable” (Blue Note)

Is Ethan Iverson the most modest guy in jazz? “Technically Acceptable” is his second album for Blue Note and it’s a virtuosic display of piano chops that goes way beyond acceptable.

Iverson is particularly fond of the trio formation, and he leads two bands here; the bulk of the tracks feature bassist Thomas Morgan and drummer Kush Abadey, with Chilean bassist Simón Willson and drummer Vinnie Sperrazza taking the reins for two tracks.

Iverson recently spoke out in defense of jazz standards, and “Technically Acceptable” makes the musical case with ease. As a jazz writer, composer and scholar, Iverson comfortably distills decades of piano stylings into his musical language. His gear changes from stride playing to blues, from chunky chordal passages to gossamer impressionistic flourishes are dazzling. He is constantly throwing back whilst looking forward.

But don’t be put off by all this talk of technique, Iverson swings seriously hard but brings the grace of a Schubertian piano maestro. His music has a steely sincerity to it, but everything is shot through with wit and playfulness – his liner note states that it is required to announce from the stage, “The next piece is ‘Technically Acceptable.’”

11 of the 13 pieces are composed by Iverson, and with all but one under the five-minute mark, “Technically Acceptable” feels like leafing through a notebook of ideas and experimentations that have been honed into their most concentrated, punchy form. The opening track “Conundrum” is a great example – written for an “as yet, unproduced TV quiz show”, it’s a fun exercise to speculate on the creative brief that inspired each track.

In keeping with jazz tradition, Iverson has always covered pop songs (to great success with The Bad Plus). Here he tackles Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly With His Song”. The impact of this song is often dulled by its ubiquity on smooth radio playlists, but Iverson makes it glow with his rich harmonisations and restrained soloing. There’s something uncanny and charged about this deeply familiar yet subtly changed rendition.

There’s also a silent movie-esque theremin-led cover of “‘Round Midnight” that’s so dripping with melodrama it deserves its own cape and candelabra. This notoriously tricky, hands-free instrument is played with singerly sensitivity by Rob Schwimmer.

In a first for Blue Note, a three-movement piano sonata rounds off the collection, and this is where Iverson explores his vast musical toolkit. Whilst still obviously jazz, his sonata rubs shoulders with Gershwin and Ravel and is dedicated to Yegor Shevtsov, a fellow pianist with the Mark Morris Dance Group who Iverson credits with helping his playing become a little more “technically acceptable”.

As appealing to purists as adventurous newcomers, Iverson is a free-thinking musician deeply embedded in jazz who you can tell loves all music. “Technically Masterful” would be a more accurate title, but where would the fun be in that?

Freya Hellier is a commissioning editor for Everything Jazz. Based in Glasgow, she has spent many years making radio and podcasts about music and culture for BBC Radio 3, Radio 4 and beyond.

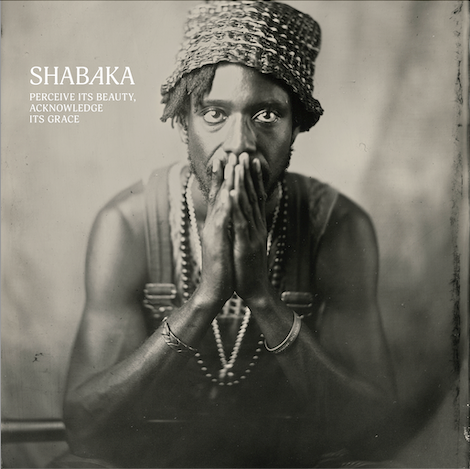

Stephan Kunze: Shabaka “Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace” (Impulse!)

There are some undeniable similarities between André 3000’s Grammy-nominated career-pivoting album “New Blue Sun” and the 2024 full-length by Shabaka Hutchings, “Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace”. A collaboration between the two seemed almost inevitable – and they have actually just released one, on Shabaka’s newest EP “Possession”.

Both artists were once known for being exceptional at their craft – Dre at rapping, Shabaka at playing the saxophone. But on their recent albums, they decided to switch things up. Inspired by the spiritual jazz of the 1970s, both turned towards the same instrument, the flute. Dre spent some years learning and honing his skills, Shabaka just a couple of months. As he’d been playing wind instruments his whole life, I’d imagine he had a slight advantage over the ex-rapper and novice.

Still, despite all of these similarities, their albums sounded very different. And even if I truly enjoyed “New Blue Sun”, Shabaka’s album is just the more mature body of work. While André’s album consists of sprawling improvisations that at times go on for ten to 15 minutes, the material on “Perceive Its Beauty” is concise and to the point. More songwriting, less noodling around.

The music sounds every bit as blissful though, all exotic flutes and paradisiac harps. One of the central pieces, “I’ll Do Whatever You Want”, is an airy electronic tune produced by Floating Points – who has worked with the late spiritual jazz legend Pharoah Sanders before his death on a brillant album – and new age icon Laaraji. Other songs feature artists as diverse as the indie rapper Elucid, singer/songwriter Lianne La Havas, or spoken word poet Saul Williams.

A lot of weight must have come off Hutchings’ shoulders by putting the saxophone to the side. His mastery of the instrument had made him a revered figure of the 2010s South London jazz scene, but in several interviews he explained how he started feeling limited by expectations, which in turn made him resent the saxophone. The flute enables him to express himself freely again, without any pressure of having to be technically perfect. (For someone who’s only played for a few months, his control over the Shakuhachi comes quite close to perfection though.)

The job of an artist is not to fulfill fans’ expectations. Their job is to listen and stay true to their inner calling – and if it calls you to start playing a Japanese bamboo flute after decades of jazz saxophone, then that’s exactly what you should do. With this record, Shabaka surely disappointed some die-hard fans but I applaud him for not taking the easy route – to me, he’s a shining example of a true artist with integrity.

Stephan Kunze is commissioning editor for Everything Jazz. He’s a writer, consultant and book author based in Germany. He publishes zensounds, a newsletter on experimental music and culture.

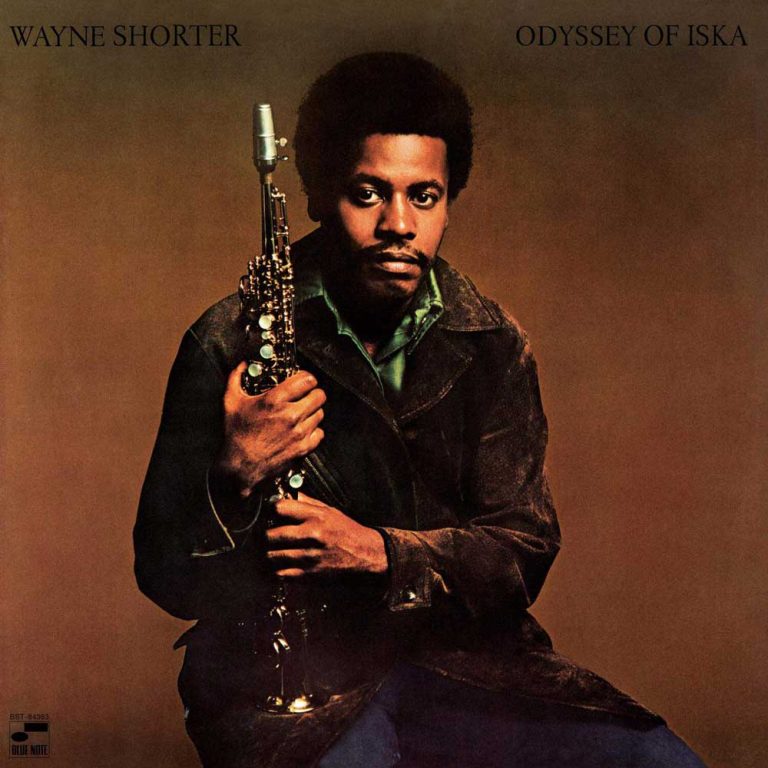

Andy Thomas: Wayne Shorter “Odyssey of Iska” (Blue Note)

Produced by Duke Pearson, recorded at A&R Studios, New York on August 26, 1970, and released the following year, “Odyssey of Iska” was the last album of Wayne Shorter’s early Blue Note period that had begun in 1964 with “Nightdreamer”.

The session took place soon after Shorter had left the Miles Davis Quintet who he had performed with and composed for since 1964 as well, and shorty before he joined Weather Report.

As such it can be listened to as a pivotal bridge album as the saxophonist sought to further his experimentations on “Super Nova” from 1969 alongside his other world jazz fusion album “Moto Grosso Feio” that resulted from the same session as “Odyssey of Iska”. I had the album on an old 1970s reissue but this year indulged myself with this beautiful 180 gram pressing as part of the Blue Note Tone Poet series.

With Shorter on tenor and soprano and a serious band that included Dave Friedman on vibes and marimba, Gene Bertoncini on guitar, Ron Carter and Cecil McBee on bass, and three drummers (Billy Hart, Alphonse Mouzon and Frank Cuomo), the album’s proto-fusion was hugely prescient. It sounds even more so now with this serious audiophile pressing, mastered from the original analogue tapes, highlighting every nuance of the incredible musicianship.

The album was recorded as a tribute to Shorter’s daughter Iska who had been born the year before with severe brain damage. The one-word titles “Wind,” “Storm,” “Calm,” “Joy,” both serve as perfect descriptions of the immersive sonic atmosphere within and point to Shorter’s spiritual path in Nichiren Buddhism.

As soon as you drop the needle on the brooding ambient jazz of the opening track “Wind”, you know this one’s going to hit hard. With Shorter’s exploratory horns navigating a deep maelstrom of marimba, bass, guitar and percussion, this was as advanced as anything on Blue Note as it entered the 1970s.

For many critics, the album’s stand out was the 12-minute version of Bobby Thomas’ “De Pois do Amor, o Vazio (After Love, Emptiness)”, illustrating Shorter’s growing interest in Brazilian music. But to my ears Shorter and his heavyweight band save the best for last on the cavernous abstract fusion of “Joy”. A sign of things to come that still sounds like the future today.

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings.

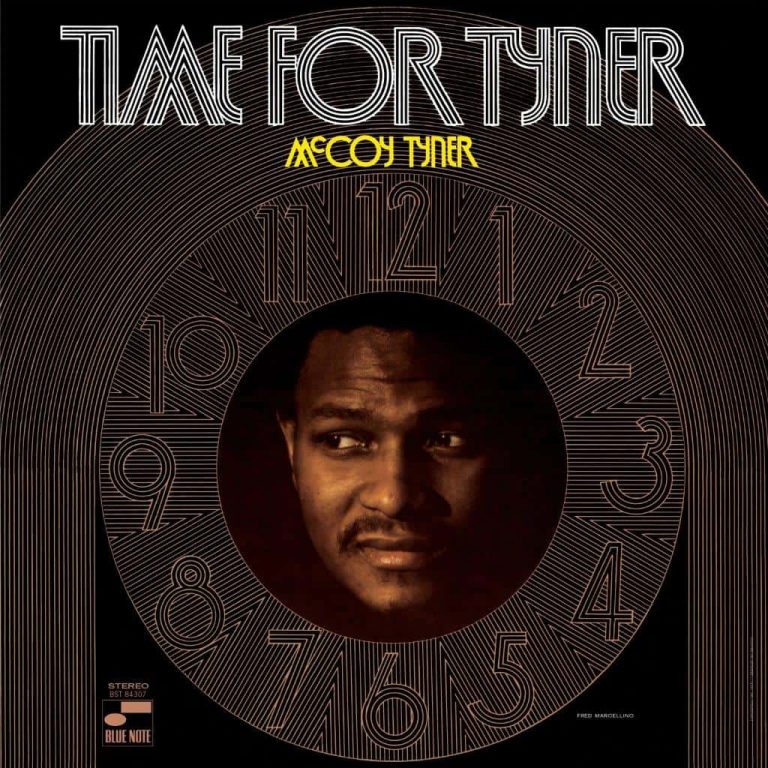

Shannon Ali: McCoy Tyner “Time For Tyner” (Blue Note)

The music I listen to the most these days is jazz from the late 1960s and early 1970s, like Charles Mingus, Herbie Hancock, Sun Ra, and McCoy Tyner. Notwithstanding the purity of their sound or the prowess of these players, you hear an overabundance of individuality, ideation, and, most importantly, freedom in every note they play. Sixty years later, we are again facing an unprecedented time when our rights as individuals are being stripped away one by one. With albums like “Time for Tyner”, these artists pushed boundaries musically and challenged our thoughts and perspectives, especially around Black identity, while America was undergoing perhaps its greatest seachange.

Rounding out John Coltrane’s quartet – alongside drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison – is no small feat, as it is arguably one of the most seminal groups in music. Tyner became an innovator of jazz piano, renowned for his intense left-hand style and vast melodic range. His gifts were boundless, one of which was his ability to create a sound that was equally melodic and percussive. I vividly recall one of his many performances at the Blue Note when I was close enough to hear his sound reverberate and feel gusts of wind each time he played.

Months shy of his 30th birthday, in spring 1968, Tyner was in search of new horizons. With his third Blue Note release (and ninth overall studio album), “Time for Tyner” features a quartet – bassist Herbie Lewis, drummer Freddie Waits, and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson – eager to take that intrepid voyage with him.

It kicks off with expansive original compositions like “African Village” and “Little Madimba” and then rounds out with standards like “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face.” “Time for Tyner” is one of the many definitive albums of this period, positioning the rhythm section front and center — sans horn or vocals. It not only showcases the immense talent of Tyner, Hutcherson, Waits, and Lewis as artists but also serves as a platform for them to collectively question, even reproach, the political climate through music.

Shannon Ali (Shannon J. Effinger) has been a freelance arts journalist and cultural critic for over a decade. Her writing on jazz and music regularly appears in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, W Magazine, NPR Music and Pitchfork, among others.