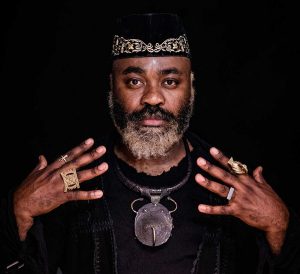

The first South African artist to be signed to Blue Note, pianist, composer and educator Nduduzo Makhathini draws on his Zulu heritage and the ancestral jazz traditions of his homeland to create healing music for a country he is deeply rooted to.

“A lot of my work speaks of cosmology, and when we think about cosmology, place is such an important factor in the way our constructs of being in the world is understood,” says Makhathini from his home in Durban. “The idea of the land is a hinge that connects the ancestors and the living, and all our rituals are observed in specific geographies…so the concept of recharging is also the concept of going back to the source.”

In the liner notes to “In The Spirit Of Ntu” his second outing for Blue Note in 2022 and 10th album since his debut for his Gundu Entertainment label in 2014 he wrote: “Our essence is ‘force’ what our ancestors called Ntu…Our ancestors understood the world as being a manifestation of this force.”

NDUDUZO MAKHATHINI In the Spirit of Ntu

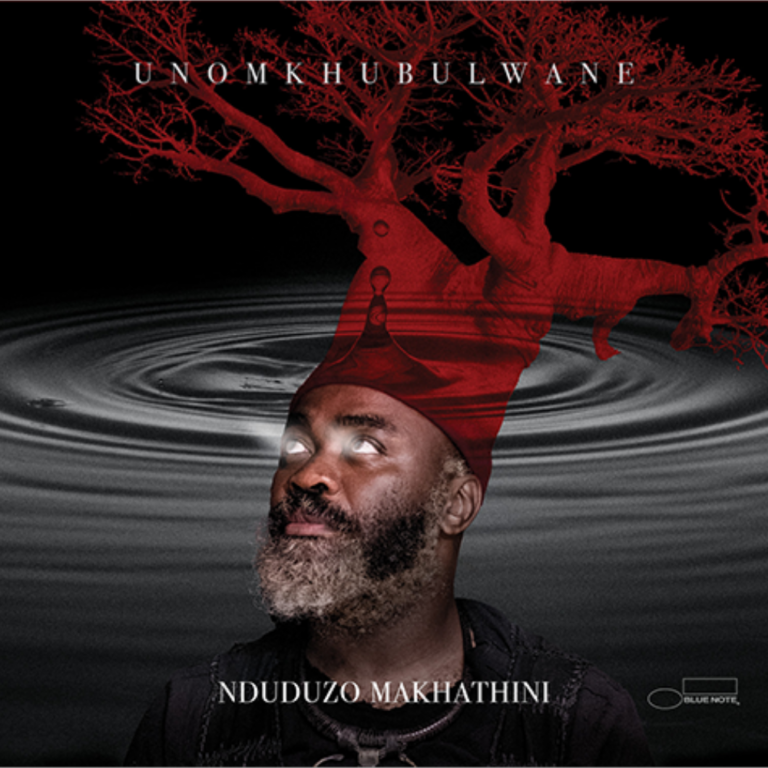

Available to purchase from our US store.This spiritual force now charges Nduduzo Makhathini’s third Blue Note album “uNomkhubulwane” recorded as a trio with bassist Zwelakhe-Duma Bell le Pere and drummer Francisco Mela. Like his previous albums, “uNomkhubulwane” is a transcendent work that speaks to an Africa disrupted by what the pianist calls “the catastrophes of the colonial time”.

Nduduzo Makhathini Unomkhubulwane

Available to purchase from our US store.Growing up in the rural hillside region of umGungundlovu (the site of the Zulu Dingane kingdom between 1828 and 1840) Makhathini first learned the art of traditional healing from his grandmother who was a Sangoma (Zulu healer). “From a very early age there was this very strong connection between song and some kind of healing potency and property inherent in the sound,” he says.

The son of musician parents (his father was a guitarist and his mother a pianist), Makhathini’s musical foundations were in the church where he sang in the choir. He only came to the piano at University but found a disconnect between what he was taught and what he had grown up around. “When I went to study music I felt it was important to question the way the music curriculum isolated sound from healing,” he says. “Healing is not a thing we are bringing to the music, it’s a holistic ecosystem that has always functioned in this way. So I was very much disorientated by that experience at University where there was no connection between spirituality and sound.”

A profound thinker, educator and researcher, Makhathini would go on to make it his goal to change systems from within, including him heading the music department at Fort Hare University in the Eastern Cape between 2015 and 2023. “We see more and more people in South Africa asking where are our stories in the syllables and curriculum,” he says. “So my coming into these institutions was kind of like a protest.”

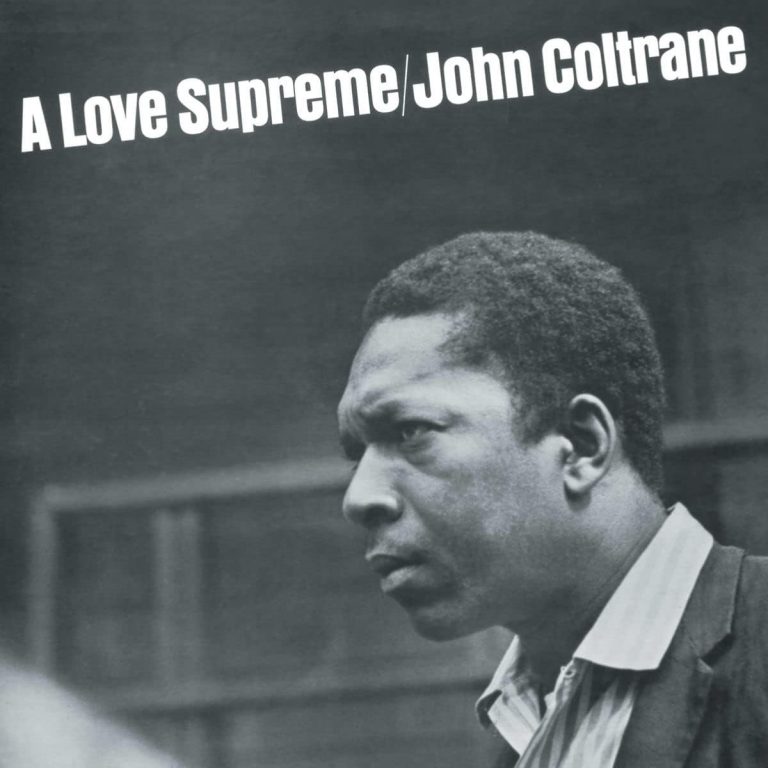

It was only when he heard John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” in a local library that he made his own connections between American jazz and spirituality. “It was like ‘this is what I’ve been looking for’, this connection between spirituality and enunciations of sound,” he says. “What really solidified this moment was reading the liner notes and hearing what Coltrane was thinking…this idea of a Supreme Being and a source where everything was drawn including the sound.”

JOHN COLTRANE A Love Supreme

Available to purchase from our US store.As he learned more about Coltrane, his music and message became even more profound. “Here was someone looking for interventions to navigate a very difficult time in the United States during the civil rights era, and of course there are parallels with what was happening in South Africa,” says Makhathini. “So for me it all comes together as a kind of collective memory.”

Shortly after his spiritual jazz epiphany, Makhathini was to meet his mentor and guide Bheki Mseleku. “My great teacher was thinking in similar ways [as Coltrane] about his spirituality and the way he was playing the music,” says Makhathini. “Also the way Bheki Mseleku plays is a way of thinking about transposing folk sounds and the indigenous music of the Zulu people into the practice of being a jazz pianist. And so the kind of music that influenced him was the same as my own.”

It was through Bheki Mseleku that Makhathini learned of the workings of John Coltrane’s classic Quartet. “What really occurred to me when I heard the piano of McCoy Tyner was that this has some connection to how my teacher Bheki Mseleku plays,” says Makhathini.

“There was this connection straight away. It was like ‘this is the way my people dance’…I think jazz comes from this echo of home. There is something very ancient about it for us. We often think of jazz as something modern that comes to us but I think it is a portal that has kept sacred practices.”

The route to his Blue Note debut of 2020 “Modes of Communication: Letters From the Underworlds”, were a series of albums recorded for his Gundu Entertainment label that took on Bheki Mseleku’s teachings. The deep spiritual jazz of Makhathini’s albums like “Mother Tongue” found their way to Shabaka Hutchings, who invited the pianist into his group The Ancestors after appearing on his 2016 album “Icilongo (The African Peace Suite)”. As well as playing on the Johannesburg recordings “Wisdom of the Elders” for Brownswood Recordings and “We Are Sent Here by History” for Impulse!, Makhathini produced fellow Ancestors drummer Tumi Mogorosi’s album “Project Elo”.

SHABAKA AND THE ANCESTORS We Are Sent Here by History

Available to purchase from our US store.Nduduzo Makhathini subsequently became a mentor to many of the new generation of South African jazz musicians such as saxophonist Linda Sikhakhane who appeared on “In The Spirit Of Ntu” and whose forthcoming Blue Note album “Inkehli” was produced by Makhathini. “The important thing for South African jazz right now is that we find a way to connect it to our indigenousness, in the same way that Philip Tabane and Bheki Mseleku and a lot of our greats did,” says Makhathini. “In post colonial times there is a tendency to leave behind this kind of rootedness. My hope is we create a kind of memory bank inside of our practice. So when people hear our music they can identify with the place and it’s not dislocated from the place in this confusion of modernity.”

For his third Blue Note album, Makhathini has chosen the trio format on a record that unleashes its spiritual power over three movements. “This will be my third trio album and I always return to this symbolism of the number 3,” he says, referring to Yoruba cosmology where 3 represents balance and harmony [characteristics of uNomkhubulwane]. “It’s also like a very democratic way of thinking about sonic spaces and figuring out a way of making decisions more quickly. It’s less easy to do that in say a quartet.”

The album takes its name from the goddess of fertility in Zulu cosmology and reveals its narrative over a conceptual suite of spiritual music and Makhathini’s Zulu vocal incantations. “The first movement “Libations” is thinking about the ways in which we appease our gods…The second movement “Water Spirits” is looking at the idea of water as abundance governed by uNomkhubulwane, and relating that to the cultural riches of Africa. Then the last movement “Inner Attainment” is thinking about using grace as a way to lift out from the gravity pulling everything down. So it’s a way to lift from all of these troubles and catastrophes as a way to heal the traumas.”

While he continues to address “the catastrophes of the colonial time” and the subsequent traumas, Makhathini’s spiritual jazz is created with an optimism for the future. “I really hope whenever people hear my music there it opens an invitation to imagine another world that is more kind,” he says. “What has been lost in society has been this ability to sense, what does it mean to feel… This is what the music is trying to activate.”

Read On…Ancestral Echoes: Nduduzo Makhathini’s In the Spirit of Ntu

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings.

Header image: Nduduzo Makhathini. Photo: Arthur Dlamini / Blue Note Records.