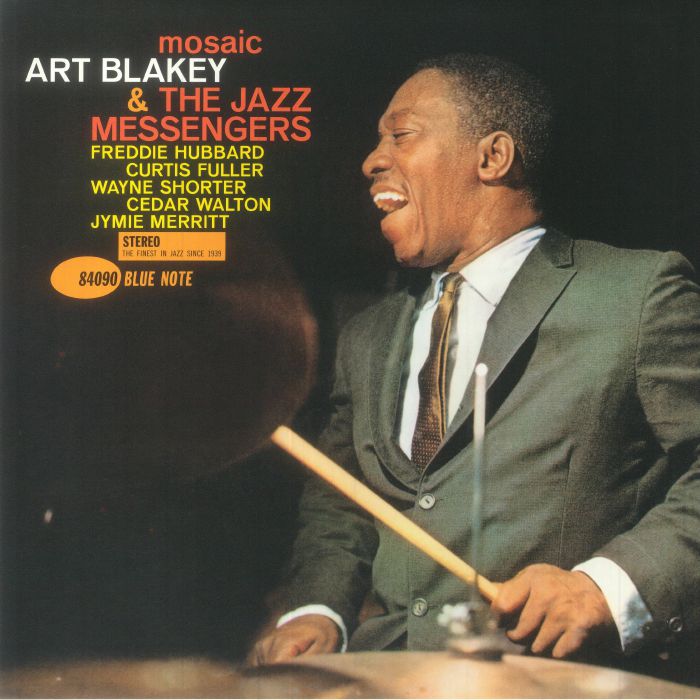

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, jazz was both high art and popular entertainment. In that brief period after the forbidding complexities of bebop faded and before the rise of amplified guitar rock, jazz – and specifically hard bop – was as much music for intellectuals to dissect and obsess over as it was the sound of a glitzy night out in a jumping club. No band captured that mix of quest and glamour better than the Jazz Messengers, led by drummer Art Blakey.

Blakey was both a canny showman and a hard driving bandleader who ran the Messengers like a cross between an academy and a boot-camp, with an ever-evolving line-up that made room for young firebrands eager to prove their worth. It meant that some of the finest and most progressive composers of mid-20th century jazz spent the early part of their careers contributing tunes to Messenger albums. “Mosaic,” recorded in October 1961 and released on Blue Note in 1962, is the perfect example.

After the previous year’s eponymous “Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers” on Impulse, “Mosaic” was the second album to feature what became the Messenger’s classic sextet formation, and included, alongside Blakey, a core backbone of players who had also been on that earlier date: bassist Jymie Merritt, trombonist Curtis Fuller and saxophonist Wayne Shorter. It also introduced two new faces, with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard replacing Lee Morgan and pianist Cedar Walton taking over from Bobby Timmons. All five tracks on the album are originals, contributed by Blakey’s young proteges.

Walton’s title track kicks it off with a show-biz fanfare, quickly making room for Blakey to lay down the kind of rich, tom-heavy, ride-cymbal-driven polyrhythms that propelled his landmark 1957 recording of Dizzy Gillespie’s “A Night In Tunisia” – and Walton’s prancing Latin chords give it a similar Hollywood-exotic feel. The tempo is typically blazing and every sideman but Merritt takes a compact solo bursting with ideas. As big-name leader, Blakey indulges in a longer solo spot, with huge rolls and crashes kept in time by his trademark unstoppable hi-hat pedal snit on the two and four of every bar.

“Down Under” is the first of two Hubbard compositions, a breezy, bluesy soul-jazz stroller with pristine arrangements making full use of the brass-heavy, three-horn front line. “Children Of The Night” is unmistakably Shorter’s tune, a tough hard bop burn that nevertheless seems to hint at some inscrutable mystery that only he can discern. As its name suggests, Fuller’s only contribution, “Arabia,” is a direct descendant of Duke Ellington’s “Caravan,” a deep, up-tempo blues groove with a dark, Saharan lilt. Introduced by a deeper-than-deep bass groove, Hubbard’s “Crisis” ends the album. It’s a masterful exercise in tension and release as a floating, descending figure repeatedly gives way to punchy bars of heavy swing, eliciting some thrilling solos, with Shorter even throwing in a cheeky, throwaway reference to “Camptown Races.”

Blakey knew he was on to a good thing with this ensemble of first-class improvisers and composers, and it would prove to be the basis of one of the most durable iterations of the Jazz Messengers. The following year, Merritt was replaced by bassist Reggie Workman (just out of John Coltrane’s group), consolidating a line-up that would stay together until 1964, recording a handful of classic Messengers albums featuring timeless compositions by Hubbard, Fuller, Shorter and Walton. They still stand as the epitome of hard bop. And they’re still glamorous as hell.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header photo: Art Blakey performs at Cafe Bohemia on January 4, 1956 in New York. Photo: PoPsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives via Getty.