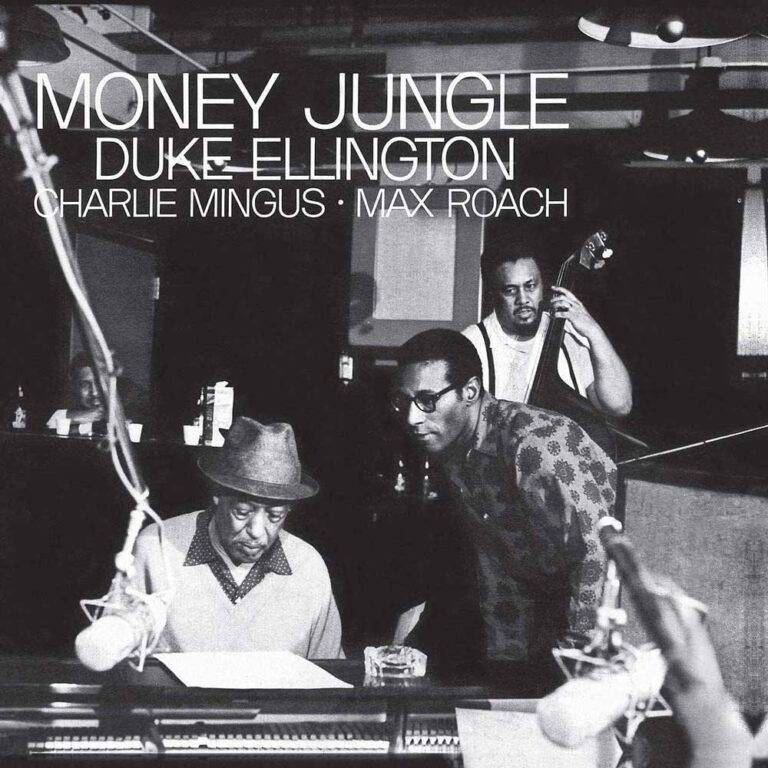

On 17 September 1962, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Max Roach gathered at New York’s Sound Makers Studio, where the Bill Evans Trio had just recorded, to make one of the greatest ever jazz trio albums.

While most successful collaborations in jazz are notable for the unity of the musicians, on this session it was friction between the three masters that drove the creativity of the resulting recording.

“How the revered and courtly maestro Ellington – who was 63 at the time – got together with two such mercurial jazz rebels as Mingus (40 at the time) and Roach (38) has remained something of a mystery all these years,” wrote Bill Milkowski in his feature for Downbeat magazine in June 2013, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the “Money Jungle” album.

In this carefully studied article, Milkowski reveals it was producer Alan Douglas who brought the musicians together. “I felt Mingus was the contemporary extension of the Ellington school,” Douglas recalled to Milkowski. “So I called Charlie and he disagreeably agreed, as usual, and he insisted that the only drummer for the session could be Max.”

With all musicians insisting that they didn’t want to rehearse together, tensions soon came to a head though. “Mingus started to complain about what Max was playing,” Douglas told Milkowski. “Mingus was getting louder and louder as the session went on… in the middle of it Max kind of looked up at Mingus and smiled and said something. And at that point, Mingus picked the bass up, put the cover on it and just stomped out of the studio.”

Eventually Duke convinced Mingus to return to the studio to record the abrasive session that resulted in “Money Jungle”. While it has gone down as one of the greatest piano trio albums of the 1960s, it was also quite unlike any other.

From the menacing attack of Mingus’s bass and uncharacteristic clanging and discordant piano of Ellington on the opening title track, the session resembled the big bands that both led rather than a paired-back trio album. As Bill Milkowski wrote, it felt as if Ellington was “duelling rather than dialoguing with Mingus as Roach cooks underneath with some hip interaction between snare, bass drum and ride cymbal.” It could also be heard as a challenge between father and son, or master and student – built out of both respect and rivalry.

Despite the disharmony, or perhaps even because of it, “Money Jungle” also includes one of the most beautiful tracks any of the three masters ever recorded. As Ellington later remembered of his instructions to Mingus and Roach for what became the jaw-dropping “Fleurette Africaine”: “Now we are in the center of a jungle, and for two hundred miles in any direction, no man has ever been. And right in the center of this jungle, put in the deep moss, there’s a tiny little flower growing, the most fragile thing that’s ever grown. It’s God-made and untouched and this is going to be ‘The Little African Flower.’”

While the album is noted for its tension and abrasion, there are other tender moments particularly on the trio’s interpretation of the jazz standard “Warm Valley” originally written by Ellington in 1940 and recorded by everyone from Art Farmer to Joe Henderson.

Lastly, the session also featured one of the most remarkable versions of Ellington and Juan Tizol’s jazz standard “Caravan” ever recorded, mining every bit of musical genius out of these three combative players.

This incredible album still has the power to move and surprise the listener, while being a constant inspiration to generations of young jazz musicians.

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings.

Header image: Duke Ellington. Photo: George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images.