Despite having just recovered from a painful throat operation which left him with that infamous rasp, autumn 1957 found Miles in peak musical and physical health. He had met his soon-to-be second wife Frances Taylor, signed with Columbia, recorded the epochal ”Miles Ahead” album and released “Cookin’” – his last collection for the Prestige label – to glowing reviews.

Miles celebrated by taking his quintet – featuring Cannonball Adderley, Tommy Flanagan, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones – on the Jazz For Moderns tour of the USA alongside George Shearing, Gerry Mulligan, Chico Hamilton and Helen Merrill. He then flew to Paris for a 30 November concert at the Olympia Theatre, which would be followed by a three-week residency at the Club St. Germain.

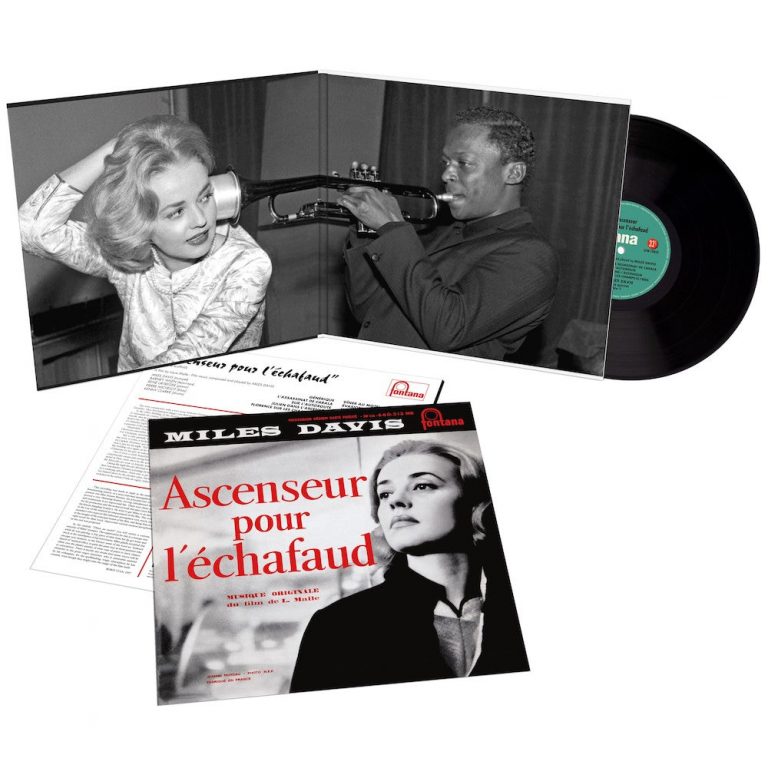

He was met at the airport by his old flame, the actress and singer Juliette Greco, and 24-year-old film director Louis Malle, a crucial figure in the burgeoning Nouvelle Vague movement. Malle had an intriguing proposition for Miles – the offer of a soundtrack for his debut film, “Ascenseur pour l’échafaud”, starring Jeanne Moreau and Maurice Ronet as a couple embarking on an illicit, murderous romance. Miles accepted the assignment, subject to viewing a rough cut.

The Olympia Theatre gig saw Miles guesting with the Barney Wilen Quartet: Wilen on tenor sax, Rene Urtreger on piano, Pierre Michelot on bass and American expat drummer and bebop pioneer Kenny Clarke. Clarke had been based in Paris since September 1956, and of course had recorded with Miles on some classic Prestige and Blue Note sides between 1952 and 1954. On 2 December, Miles attended a screening of “Ascenseur”, reportedly taking a few notes and getting some translated explanations from Malle. Two days later, he gathered Wilen, Urtreger, Michelot and Clarke to record the soundtrack at Le Poste Parisien (in his autobiography, Miles claims he chose the studio for its ‘gloomy, dark’ ambience).

According to Clarke, the actual session lasted little more than three hours, starting in the early hours of 5 December, with Moreau reportedly passing out drinks from a makeshift bar. Miles would occasionally write down a few chords for Urtreger and Michelot’s benefit, but generally arrangements were suggested on the spur of the moment, the whole band reacting spontaneously to scenes being shown on the studio’s big screen.

What emerged was an atmospheric, striking exploration of modes and scales, famously investigated further on the epochal “Kind Of Blue” album recorded just over a year later. Miles’ playing demonstrates his mastery of the Harmon mute, as well as some of his fastest, most nimble playing on record, accompanied by Clarke’s extraordinary brushwork. Miles’ trumpet was also often recorded via the studio’s echo chamber, giving the whole album a beguiling, ethereal ambience.

The soundtrack completed, Miles finished his Club St. Germain residency and returned to New York City on Friday 20 December 1957, immediately recalling John Coltrane on tenor saxophone and Red Garland on piano to the celebrated sextet which recorded the legendary “Milestones” album two months later.

“Ascenseur” was clearly the catalyst for one of Miles’s great periods. The terrific album – originally released in Europe on 10-inch disc and in America as the Grammy-nominated “Jazz Track” alongside Miles’s June 1958 sessions with French pianist/composer Michel Legrand – earned a five-star review from Ralph J. Gleason in Downbeat magazine. And it only seems to become more critically lauded as the years go by, emphasised by the fact that both recent major Miles documentaries – Mike Dibb’s “The Miles Davis Story” and Stanley Nelson’s “Birth Of The Cool” – explore the soundtrack at some length.

Matt Phillips is a London-based writer and musician whose work has appeared in Jazzwise, Classic Pop, Record Collector and The Oldie. He’s the author of “John McLaughlin: From Miles & Mahavishnu To The 4th Dimension”.

Header image: December 5, 1957. French actress Jeanne Moreau listening to an improvisation on the trumpet by Miles Davis for the film “Ascenseur pour L’échafaud” (Lift to the Scaffold) by Louis Malle. Photo: Keystone/Getty Images.