There is nothing quite like the magic of a ‘live’ album. It captures moments fleeting yet eternal: the intake of breath or hushed tones of audiences in auditoriums marvelling at artistry; the glee of an incredible solo; the exploding rapturous applause as one song fades; the collective joy at the beginning of a tune that the audience recognises. Those moments linger beyond living memory. They are sounds captured in aspic, ever fresh, ever new.

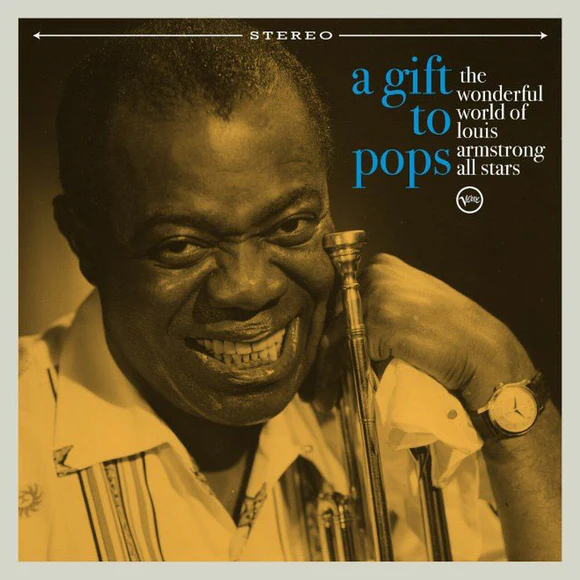

The forthcoming Louis Armstrong album, “Louis in London,” is such an album. Not only is it being released on vinyl and digital platforms, but it is also accompanied by the original video footage captured by the BBC. According to Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, it was one of Armstrong’s proudest achievements.

Ricky Riccardi is the ultimate griot on the work, life and times of Louis Armstrong – the author of three Armstrong biographies and a GRAMMY award winner for Best Album Notes. We sat for a chat down the line, and his incredible enthusiasm for all things Louis Armstrong bounced energetically through the screen. Ricky considers Louis Armstrong the most influential musician of the 20th century, revolutionising both instrumental and vocal music. He explained the history of how the album came about.

“In the summer of 1968, based on the popularity and success of “What a Wonderful World,” Louis booked a tour of England in the summer of 1968. The BBC hired him to do two TV shows on July 2nd with his All Stars band. Armstrong does the shows and goes back on tour, and then two months later, in September of 1968, he ends up in intensive care. And he has trouble with his heart, trouble with his kidneys. He goes home for a few weeks. Then, in Early 1969, he ends up back in intensive care. Then doctors tell him, ‘You need to retire.’ Armstrong had always loved making reel-to-reel tapes. So, his wife Lucille remodelled his den while he was in the hospital. And had new tape decks put in. She was trying to convince him to stay home and off the road. So Louis, as part of his recovery, starts making reel-to-reel tapes, and we at the museum have the tapes, his catalogue book in his handwriting. The BBC sent him an audio tape of the shows from July ‘68. And he takes one listen and falls in love with it. He realised that he and the band were in such great form.”

Ricky has written extensive liner notes to accompany the album’s release, 53 years after the passing of Armstrong, revealing the stories behind many of the songs. The tracklist is a delight for any collector, from the swinging ‘Hello, Dolly!’ to the nostalgic ‘Blueberry Hill’. There’s joy and pathos on the album, “In Armstrong,” says Ricky, “There’s the trumpet player, the vocalist, the showman, the MC. He does it all, but he’s also a gifted comedian. If you want to experience the total Louis Armstrong, this album has covered all bases.”

The tune “Rockin’ Chair,” a song Louis originally recorded with Hoagy Carmichael in December 1929, was the first interracial vocal duet in recording history and is a real example of Armstrong’s comedy chops. Ricky concurs, “By 1968, it’s 40 years since the original recording. He’s probably doing 300 nights a year and has done this routine thousands of times, but it still sounds fresh when you listen to it. It’s still so funny. Tyree Glenn, the trombonist, is his comic foil on that version. And it’s so warm. It’s so touching. You smile, and you can sense the love between the two of them.” “But then also,” he continues, “Don’t sleep on that opening trumpet solo because he comes in playing the melody up an octave. You would think it was the Armstrong of the 40s or the 30s because he sounds so strong, and when folks see the video, you’ll see the confidence in his face too because he knows, he’s like, ‘man, I’m on fire tonight’.”

The Louis Armstrong Museum in Corona, Queens, New York, where Ricky is based, is an astonishing tribute to Louis Armstrong’s life and legacy. It showcases his home and archival treasures. But it probably would not exist without the determination of Armstrong’s fourth wife, Lucille, says Ricky. “Armstrong married Lucille Wilson in 1942. and their honeymoon was six straight months of one-nighters, laughs Ricky. Eventually, Lucille said, ‘This is not what I signed up for.’ So Lucille, who had spent part of her childhood in Corona, Queens, found out a home was for sale. 34-56 107th Street and purchased the home without telling Louis, moving in with her mother. Eventually, when Louis was ending his tour, she said, ‘Surprise, I bought a house!’ He looked at it and fell in love with the house and the neighbourhood. And from 1943 until his passing in 1971, that was home in Corona, Queens.”

But how did the house become a museum? “After Armstrong’s passing, Lucille spent the next 12 years of her widowhood dedicated to Louis’ legacy. She saved his tapes, trumpets, and scrapbooks and had the house declared a national historic landmark. She also gave several interviews in which she talked about opening a memorial museum one day. Unfortunately, she passed away in 1983. But at that point, the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, Queens College, and the city of New York pitched in, and the house was preserved. It was opened up as a museum in 2003.”

And that’s not all, he continued enthusiastically, “Last year, 2023, we opened up the Louis Armstrong Center, a brand new museum right across the street from the house. It’s the new home of the archives, which I administer. There’s a 70-seat performance venue. There’s a gift shop. Jason Moran curates an exhibit. And so now people are coming to Corona. Our visitorship has doubled. People are coming to see the new museum, see the archival treasures, catch a show and then walk across the street and around Louis and Lucille Armstrong’s home, no one’s lived there for 40 years. So all the furniture is in place, and the paintings are on the wall. It’s like going into a time portal.”

Armstrong was an avid collector of his own memorabilia and a kind of Samuel Pepys documenter of his own life. What treasures does the museum have?

“If some unknown jazz musician, some sideman in the 50s, were making reel-to-reel tapes, scrapbooks, and photos, that would be a treasure.” reflected Ricky. “But this is Louis Armstrong. So the fact that jazz’s greatest genius, this pop icon, jazz icon, world icon, is recording reel-to-reel tapes, telling stories, arguing with his wife, complaining about racism, telling dirty jokes, putting his whole life out there? There really is nothing else like it in the world. And then,” he continued, “he’s designing collages. There’s Armstrong, the visual artist. He’s cutting out photographs, newspaper clippings, and scotch taping them to the outside of the boxes. He’s writing letters to fans. He’s making scrapbooks. We have over 80 scrapbooks. We have all these autobiographical manuscripts. For instance, Louis wrote things about the barbershops in Queens and the Jewish family that was important to him when he was growing up in New Orleans. He wanted to make sure that he would be remembered by history.”

Among the many treasures in the museum, according to Ricky, at the very entrance of the museum is a substantial photograph of Louis and Lucille in Egypt. Armstrong had a deep affinity for Africa and made several trips there, where he was much celebrated.

He played his first gig in May 1956 in Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast. “In the year before, it became the independent nation of Ghana; he spent three days there, and the whole country welcomed him like a hero. They met him at the airport. They sang ‘Sly Mongoose’, changing the lyrics to ‘All for You, Louis’. And he came off the aeroplane singing and playing with them.” He performed outside in front of 100,000 people. He played for Kwame Nkrumah, the first African-born Prime Minister of Ghana, and he told Lucille, ‘I told you we came from here because I told you we would. You didn’t believe me, but I proved it.’ And so that was just his first little trip, but he always wanted to go back.”

According to Ricky, he got the opportunity to do so because in October 1960, Pepsi opened a series of bottling plants in West Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria, and they thought it would be a great idea to have Louis Armstrong come to Africa to help promote it. “By this point,” said Ricky, “the US State Department had developed the Jazz Ambassadors program, sending jazz musicians overseas. So they got involved and said, ‘Hey, if you’re sending Louis Armstrong to West Africa, we’ll send them all over the continent’. And so Armstrong did this tour from October to November 1960. Then he took a month off to film Paris Blues, the Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier film. And then he went back in January 1961. And he pretty much covered the whole continent. He didn’t make it to South Africa but spent at least two weeks in Nigeria and Ghana. He went into Kinshasa (formerly Leopoldville) during the civil war! One of his favourite stories to tell was about how they called a truce because he, Louis Armstrong, had shown up, and for 24 hours, he said both sides sat next to each other at his concert. And as soon as his plane left, the war resumed.” Ricky chuckled.

But his tour of Africa didn’t end there, according to Ricky. “On his last day in Africa, he visited the great Sphinx of Giza in Cairo. And we have all the beautiful photos. When people visit the Louis Armstrong Center, our new museum, the first photo that hits you when you walk in is Louis Lucille and the Great Sphinx.”

Ricky is such a wonderful raconteur that our supposedly short interview turned into a much longer session than initially planned. We discussed the role of the strong and influential women in his life, including his mother, wives, and musical collaborators, and their impact on him. This led Ricky to reveal his next secret project. “Well, I’ll spoil this right now. My next book is dedicated to the women in Louis’ life. Because this was somebody who was not afraid of strong women.”

We discussed how Armstrong’s recordings and performances significantly impacted many jazz standards, such as ‘Mack the Knife’ and ‘When the Saints Go Marching In.’

And we discussed how Armstrong, being a civil rights pioneer, used his platform to speak out against racial injustice and break down barriers for his race. Armstrong was hurt that his own people did not recognise the civil rights work he often did behind the scenes. “A reporter once asked him,” mused Ricky, “ ‘We don’t see you out there marching.’ And he replied, ‘Listen, the best thing I can do for the cause is play my trumpet. If I was going to go out there and march, the first thing the police would do is hit me in the face, and I wouldn’t be able to play the trumpet anymore. And so the reporter goes, ‘You really think they would hit you, Louis Armstrong?’ And he said they would beat Jesus Christ if he was black and marched. And that was headline news all over the world. A lot of that was not well reported during his lifetime.”

Ricky is also quick to point out the value of the archival treasures at the museum to help debunk some of the stories about Armstrong and the civil rights movement. “Armstrong appears in over 30 films, and the amazing part is that he left behind a record. He made reel-to-reel tapes. He wrote down stories. He told stories, incidents of racism on film sets and what he had to go through. And you hear these tapes, and you read his writings, you’ve sensed the hurt, you sense the anger, you realise… what he had to go through every day, day in and day out and still go on stage and project joy and project love and warmth and how hard that was. And he did it till the end.”

Despite this being his life’s work, Ricky had never seen Louis Armstrong perform. I wondered what era he would have liked to have seen him in concert. “If I could go back to hear Armstrong live?” He paused, “Maybe with King Oliver in 1923 or his big band in 1938 or the all-stars, you know, in the mid-fifties. I could pick any era… to hear some of that trumpet magic in person. But I can dream. Can’t I?” He smiled.

Despite Louis’s much-celebrated life, he had hoped that when he died, he would receive a New Orleans traditional send-off from his peers known as the ‘Second Line’, but that was not to be according to Ricky. “That is actually one of the sadder stories because he had talked about it for years ahead of time. He said, ‘When I die, cats are going to come from all over the world. They’re going to love blowing over for me. They’re going to, it’s going to be great.’ And his wife, Lucille, like I said, I can’t praise her enough, but she was not from that culture, you know? And so she, she would hear him talk about it. But when he died, she wanted a very quiet, dignified ceremony. Al Hibbler and Peggy Lee sang the Lord’s Prayer. It was a very quiet occasion.”

He continued, “In New Orleans, though, that’s where the party happened. He wasn’t buried in New Orleans. The funeral didn’t happen in New Orleans, but there is footage of the whole city hall area, with thousands of people; every brass band came out, and they tried giving speeches. And at one point, I think the mayor said, you know, if you don’t quiet down, we will have to stop. And nobody quieted down. So they stopped the speeches, and everybody played and played. And it was beautiful. There’s a trumpet player in New Orleans, Teddy Riley. They gave him Louis Armstrong’s first cornet, which he first played when he was first in the Coloured Waif home, and Teddy Riley played taps on it. So New Orleans sent him out the right way, but up in Queens, it was a little different, quieter, dignified, and probably not what he would have wanted, but his hometown had him covered.

Is there still more to learn about Louis Armstrong? “There is,” says Ricky assertively. “It’s a lifetime study. I’ll say that. I’ve written two books on Armstrong because I figured a lot of people knew about his early kind of rags-to-riches story. But my first book, What a Wonderful World, was about the last 25 years of his life. My second book, Heart Full of Rhythm, was about his middle period, just the big band years. I figured those two eras were unknown. So, I wanted to share all my research and everything I had learned. But about four or five years ago, I started researching Armstrong’s early years and found new sources, interviews with his second wife, Lillian Hardin Armstrong. Unedited autobiographical manuscripts and oral histories of the musicians he played with in New Orleans surfaced.

And so I’m happy to announce I do have another book coming out. Stomp Off, Let’s Go, the Early Years of Louis Armstrong, coming out in February of 2025. And so that’ll be the end of my trilogy, but it will not be the end of my learning. I mean, just a week ago, a fan in Australia wrote to me. And sent over three letters Louis Armstrong wrote to a fan in 1938. And my jaw just hit the ground. They have Armstrong writing about the new bandleader in town, Count Basie. And how he’s listening to Duke Ellington, and I was just like, my goodness. So, whenever I think I’ve heard it all, something comes out of the blue. And I feel like for years to come, people are going to keep discovering letters. People are going to keep discovering photographs. There’ll be more concert recordings and films and stuff. So I’m in it for the long run. I’m all Armstrong all the time, and I’m just getting started.”

The Louis Armstrong House Museum is located at 34-56 107th Street, Queens, NY 11368 www.louisarmstronghouse.org

Jumoké Fashola is a journalist, broadcaster and vocalist who currently presents a range of Arts & Culture programmes on BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4 & BBC London.

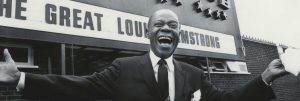

Header image: Louis Armstrong outside the Batley Variety Club in London, 1968. Photo: Louis Armstrong House Museum.