Leon Michels initially set out to become a great saxophonist. For about five years, jazz became his whole life, starting in the eighth grade and continuing into high school. “All I listened to, and all I played was jazz,” says the 42-year-old multi-instrumentalist. Michels soon realized, however, that he was not a bebop musician.

“The guys that I loved [were] like those like hard bebop guys, but I could never really play that music that well. I always liked the more lyrical guys, like Johnny Hodges and Lester Young. And that’s why I phased out of jazz because most of the stuff I liked in jazz was like pop music of the time, like Duke Ellington. I wanted to be like Sonny Rollins, but I knew that was never going to happen.”

When Michels first listened to Lou Donaldson, he soon found his lifelong path into soul music, notably The Meters and James Brown. “I met Gabe Roth and Philip Lehman at Desco, which became Daptone Records, and they signed my band to their label in high school. They would make us mixtapes, showing us more unknown soul stuff from that era.”

At 16, Michels became one of the founding members of the label’s Brooklyn-based house band, the Dap-Kings. The award-winning revivalist group was integral to Amy Winehouse’s final album, Back to Black. They also backed artists like Lee Fields and the late Sharon Jones and Charles Bradley, two astonishing vocalists whose stardom arrived later in life before their untimely deaths in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

“[Sharon] was just amazing. It kind of makes sense why it took so long for her to be famous. The thing about Sharon was she had this insane connection to the audience, like something I’ve never seen. Charles Bradley had it, too. Sharon was a wedding singer for like 30 years. I played weddings with her, and it was unbelievable how good she was. Part of Sharon’s success was the amount of touring she did, and if you saw her once, you were a fan forever. It’s not like she had hits, just this force of nature you had to experience.”

Michels continued to explore his musical influences when he formed the El Michels Affair ensemble in 2002. Seven years later, they released their second album, “Enter the 37th Chamber”, an instrumental cover of the seminal 1993 debut from hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan.

“Scion Cars had all this money to burn at one point, and they were marketing to young people because it was some affordable car. They did these concert events that would pair hip-hop artists with live bands. We were the first because I had a friend who was somehow associated with Scion, and they put us together with Raekwon.”

“We thought it would be cool to make a record of live interpolations of hip-hop, and at the time, that sort of hadn’t happened before. So we did a bunch of concerts that turned into bigger things with more Wu-Tang members and did that for maybe a year. I was always a Wu-Tang fan, but it was surprising how well these hip-hop songs held up as instrumentals when we were learning the music ahead of time. Hip-hop instrumentals can often be great, but it’s usually just a loop, right? The production is so layered and crazy that we’d be playing, and at times, it [would] sound like 1970s spiritual jazz.”

After co-founding Truth and Soul Records in 2004, Michels says his focus shifted towards production. In addition to Lee Fields, he worked with many artists of diverse genres, from Aloe Blacc’s hit “I Need a Dollar,” Beyonce & Jay-Z’s side project, The Carters, Lady Wray, and most recently, Norah Jones on her latest Blue Note release, “Visions”. Michels also serves as a musician and co-songwriter for several of the tracks. As “Staring At The Wall” begins, it evokes Phil Spector’s Wall of sound, only in the sense that you can hear Michel’s production hand of hollow vintage, lo-fi warmth from the very beginning.

“I met Norah probably somewhere around 2016 or 2017. She was working on a record and called Dave Guy and me to do horns for [it]. That’s how we met. She occasionally called us to do the horns whenever she needed them. Then she moved up to Hudson [Valley] during the pandemic, and I lived upstate. We just started talking at one point. It was the pandemic, so we hadn’t gotten to anybody then. When it loosened up, she came over, and we just jammed.”

“There wasn’t a concept. I think [the songs] came together like halfway through the record. When we started, we were just writing. Maybe Norah had a different idea, but in my head, I was like, ‘Oh, we’re just making these songwriting demos,’ so I would put one mic on the drums and haphazardly one mic on the piano, but a lot of those like, quote-unquote demos just became the recordings. We tried to recut them with different musicians, and the feeling never really got better — it actually got worse.”

“I think her songwriting was very open, and a lot of the songs came together really quickly. [Norah] would come over and have like these loose ideas. She would come over while the kids were at school, so from 10 am to 3 pm, and we would usually knock out a song within that timeframe.”

NORAH JONES Visions

Available to purchase from our US store.Shannon J. Effinger (Shannon Ali) is a freelance arts journalist in New York City. Her writing on all things music regularly appears in The New York Times, Washington Post, Pitchfork, Downbeat, and NPR Music.

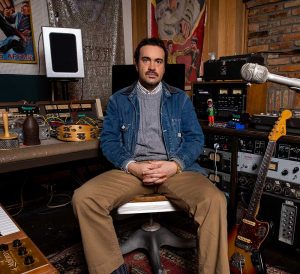

Header image: Leon Michels. Photo: Mike Lawrie. Courtesy of Big Crown Records.