Developed at ‘after hours’ jam sessions in clubs such as Minton’s in New York – though the fertile Kansas scene also played a part – bebop has proved to be one of the most enduring and influential schools in the whole history of jazz. The brilliant trumpeter and occasional vocalist, Dizzy Gillespie used the term bebop in his scat solos, but “Bebop” was also an instrumental song that defined the style as it emerged in the early 1940s, growing from swing, which had hit a commercial peak in the 1930s.

With its bitingly aggressive, if not confrontational intro, and choppy staccato theme, “Bebop” was the statement of serious intent of a new generation of players that also included saxophonist Charlie Parker, guitarist Charlie Christian and drummers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach. They led quartets or quintets, whose sparky, snappy complexity boldly broke from the vibrato-laden smoothness of big bands. Parker’s “Ornithology,” “Billie’s Bounce” and “Confirmation,” Gillespie’s “Dizzy Atmosphere,” and Tadd Dameron’s “Hothouse” are exhilarating bebop classics that have become a pivotal rite of passage for today’s jazz musicians.

Get to know the bebop sound with these classic albums which belong in every jazz lover’s collection

Alto saxophonist Parker remains one of the most iconic figures in all of jazz history as much for his preternatural talent as a turbulent life that led to a premature death. Collated from several 10” releases in the early 50s, this album is the perfect introduction to his genius. His excellent quartet comprises either Hank Jones or Al Haig on piano and Percy Heath or Teddy Kotick on double bass, but drummer Max Roach is the common denominator on all sessions, and his relationship with the saxophonist is crucial. Both have the same rhythmic dynamism and daring, and ability to raise the intensity of the music at opportune moments. While the darting, whirling theme of “Confirmation” is a highlight the bluesy drawl of “Cosmic Rays” is beautiful.

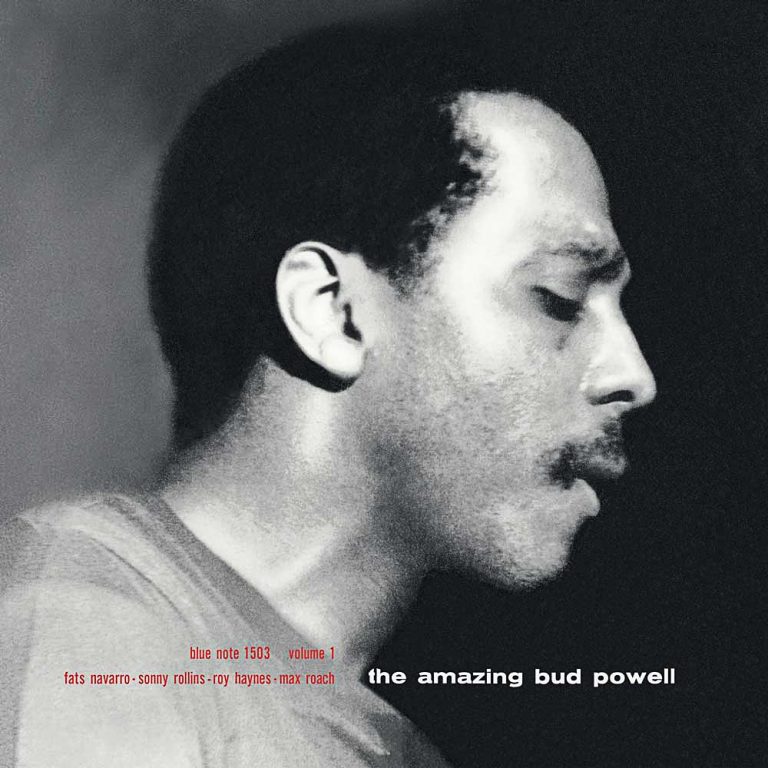

To a large extent Powell was to the piano what Parker was to the saxophone. He had advanced rhythmic ingenuity and great harmonic imagination that enabled him to make music that had a strong, sometimes pummelling beat and a range of tonal colour that could be dazzling.

Although Powell could rightly lay claim to being the premier pianist of the bebop movement, his contribution to the vocabulary of the piano trio in particular was crucial. “The Amazing Bud Powell,” compiled from several 10” releases shows the superb chemistry he had with drummer Max Roach and double bassist Curly Russell. Songs such as “Un Poco Loco,” with its upbeat, energetic Latin flavour convey the vibrant, if not mischievous character of bebop as well as its artistry.

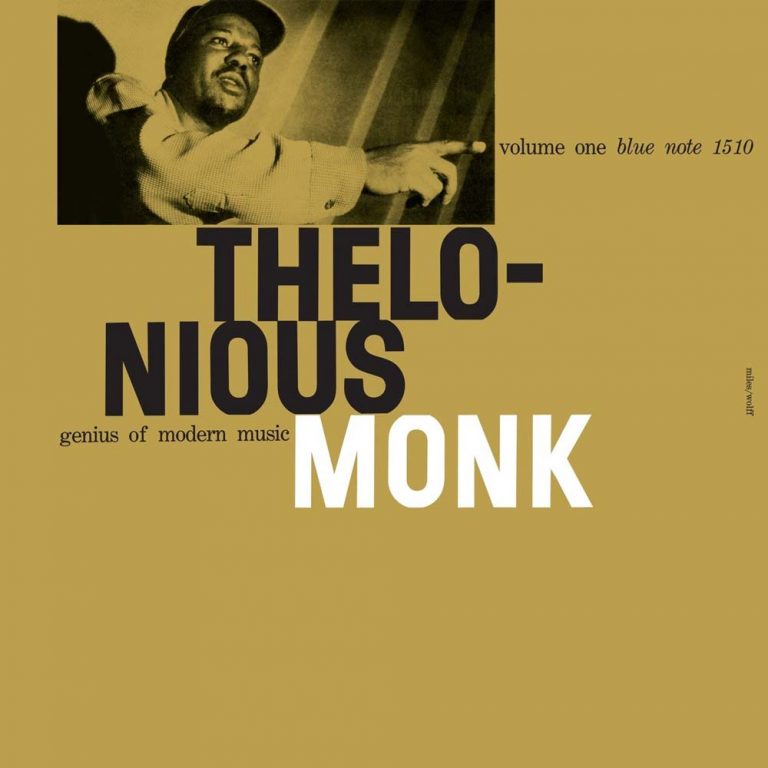

Although dubbed the ‘High priest of bebop’ Thelonious Monk wrote such unique songs that it is difficult to shoehorn him into any genre. “Genius Of Modern Music” is indeed the most appropriate term for his body of work and this 1956 compilation of tracks recorded between 1947 and 1948 captures the pianist in a purple patch of his career.

It is almost as if Monk were somehow making the blues bracingly futuristic and playfully wry, as the jaunty themes and skippy rhythms of classics such as “Well, You Needn’t,” “Epistrophy” and “In Walked Bud,” a joyous tribute to fellow pianist Bud Powell, stick in the mind as soon as they are heard. Monk’s excellent bands feature the likes of saxophonist Sahib Shihab and drummer Art Blakey. The spiky humour of the music they made is undeniable, but so too is its profound solemnity, as epitomised by the timeless standard “Round Midnight.”

Read On…Ancestral Echoes – Nduduzo Makhathini’s “In the Spirit of Ntu”

Kevin Le Gendre is a journalist and broadcaster with a special interest in black music. He contributes to Jazzwise, The Guardian and BBC Radio 3. His latest book is “Hear My Train A Comin’: The Songs Of JImi Hendrix”.

Header image: Portrait of Thelonious Monk, Minton’s Playhouse, New York, N.Y., ca. Sept. 1947. Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress.