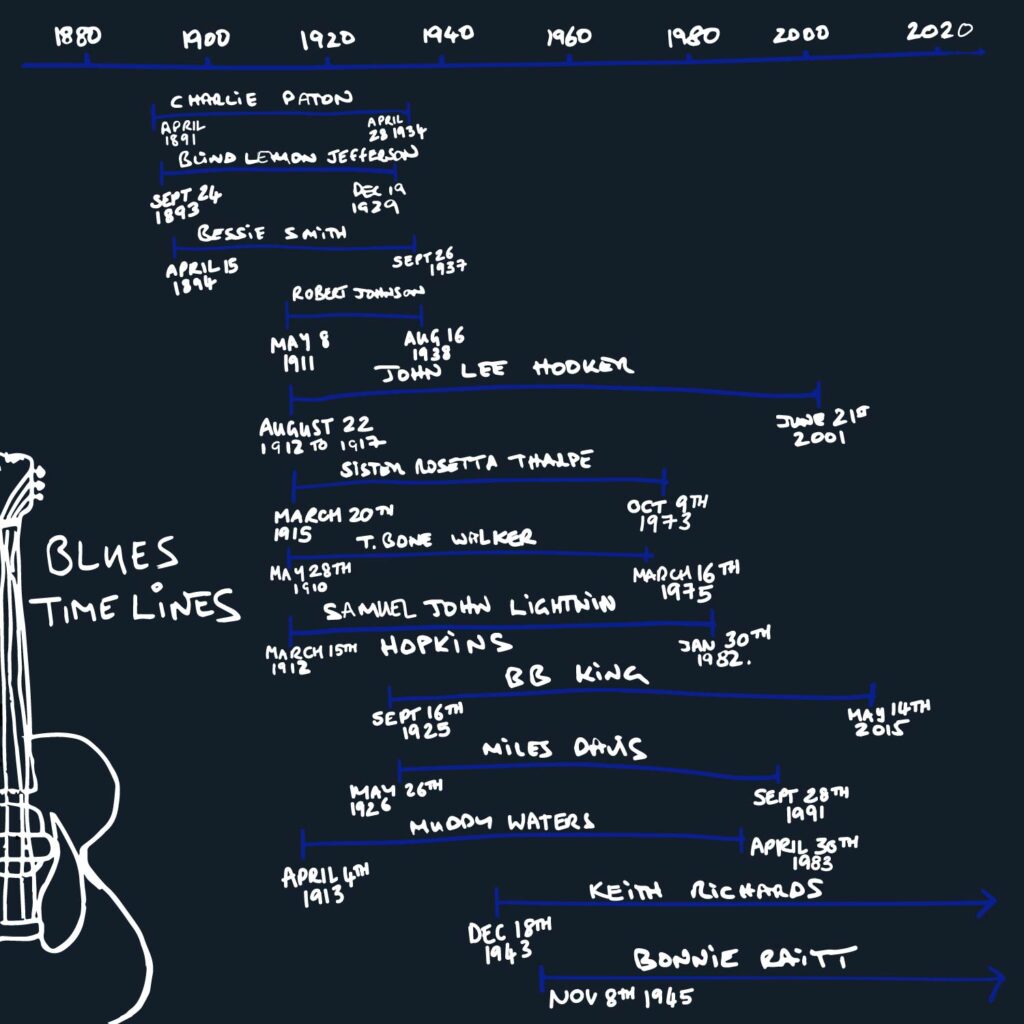

By the mid 1960s it had been almost twenty years since Sam ‘Lightnin’ Hopkins had his first hit with “Short Haired Woman” in 1947 or John Lee Hooker’s “Boogie Chillin” had been released in 1948. Then the blues was seen as ‘race music’ marketed only to black audiences. The release of these albums at the time aimed to bring these artists to the attention of a white mainstream audience.

There are many parallels in the lives of these two bluesmen. They were born out of the southern rural wellspring of African American music, albeit in two distinct parts of the blues map. In both of their music is the brooding threat of violence, pain and hurt but also the promise of freedom, sexual love and the pleasures of Saturday night.

Sam Hopkins was born in Centerville, Texas on March 15, 1912. He met blues legend Blind Lemon Jefferson at a church picnic in Buffalo, Texas. He told filmmaker Les Blank in 1967: “You know The Blues is hard to get acquainted with like death… the Blues will dwell with you every day and everywhere.” The proximity to white mob violence was all too real to Hopkins. In front of the courthouse in Centerville was a hanging tree, or ‘tree of justice’ used to lynch African Americans until 1919.

The year and place of John Lee Hooker’s birth is mysterious and disputed but it is agreed that his birthday is August 22 – although the year is thought to be between 1912 to 1917. It is recorded that he was born in Tutwiler, in Tallahatchie County, in the Mississippi Delta, although others say his birthplace was near Clarksdale, in Coahoma County. He left there as a teenager, but he carried the accent of the delta with him forever.

Sam ‘Lightnin’ Hopkins got his name in Houston through working with a barrelhouse piano player, Wilson Smith, who used the name “Thunder.” Hopkins’s fast single-note guitar fills earned him the name “Lightnin’.” While the sixties Verve album presents him with a jazz backing, the elements of Hopkins’s music are the interplay between guitar and voice. Blues storytelling is there on in tunes like ‘Cotton’ which tells of the life of a field hand, and ‘Hurricane Betsy’ which devastated Florida and Louisiana in September 1965. His fingerpicking guitar style combined driving droning notes played with a thumb pick and fast melodic lines voiced simultaneously with his fingers and influenced guitarists that followed from Jimi Hendrix to Stevie Ray Vaughan.

The guitar and voice are the heart of John Lee Hooker’s blues style too. Rolling Stone Keith Richards stressed “he was the last of the great solo guitar players, a throwback even in his own time. He was a guy more in line with Charley Patton or Robert Johnson, a one-man band, totally his own man.” The strutting shuffle ‘Shake it Baby’ on this album is a good example of his boogie style. It builds emphatically as John Lee calls out to his love interest to shake it ‘one more and one more time.’

Miles Davis, who collaborated with Hooker on the soundtrack for the movie The Hot Spot described him as “the funkiest man alive”. That trace is here in these recordings in the tales of drifting country boys, prodigal sons and sweat-stained southern night. Singer Bonnie Raitt said of him: “he had that cry in his voice that would just break your heart. Sometimes when he was playing, it was like he’d never left Mississippi, and there had never been any civil rights or any money for him or anything. He could authentically tap into all the pain he’d ever felt.”

These albums present acoustic blues in the context of a jazz band. At the time of the recordings both artists had reached their forties. “Lightnin’ Strikes” which was released on the Verve Folkways label, and recorded in Los Angeles with a rhythm section of Jimmy Bond on double bass and Earl Palmer on drums. Bond had performed with Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk as well as Chet Baker and was a member of the Wrecking Crew elite session players. Earl Palmer, born in New Orleans, played on thousands of hit recordings from Little Richard to Frank Sinatra. They provide solid but pedestrian grooves, while Don Crawford’s blues harmonica on “Mojo Hand” and ‘Woke Up This Morning’ is more in keeping with a blues feel.

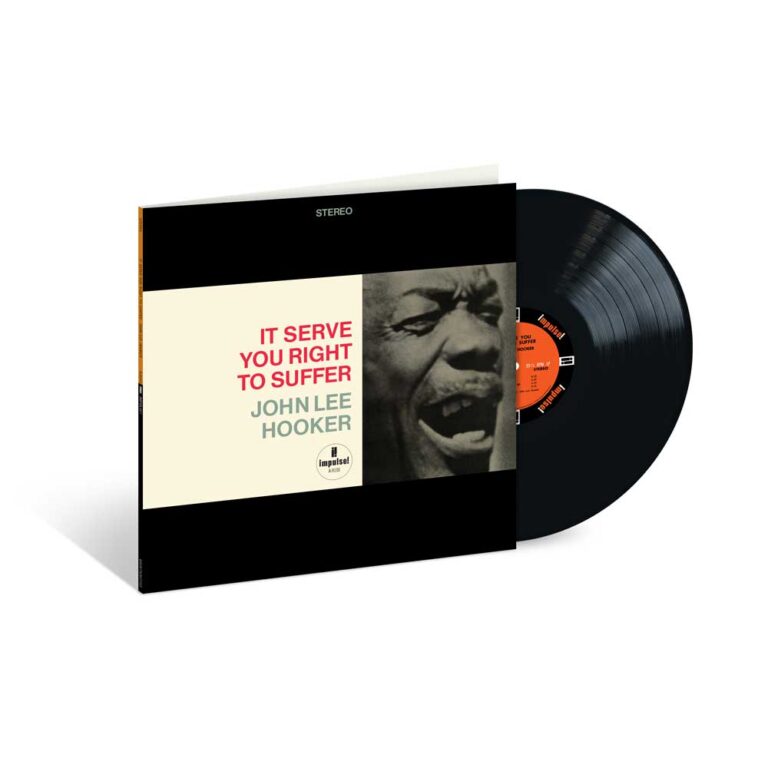

“It Serves You Right to Suffer” is the only album Hooker made for the Impulse! Label head Bob Thiele took personal control of the session which took place on 23rd November 1965 and assembled crack session musicians from the New York jazz world. This included fellow Mississippian Milt Hinton on double bass. Hinton was a member of the Cab Calloway orchestra in the 1940s and was a seasoned New York session bassist recording with Billie Holiday and Sam Cooke amongst many others. David ‘Panama’ Francis was on drums; another New York session man whose credits included hits like Bobby Darin’s ‘Splish Splash’ and ‘Reet Petite’ for Jackie Wilson. Jazz guitarist Barry Galbraith provided a second guitar which is sensitive, providing delicate supportive texture to John Lee Hooker’s expressive style.

The album contained a mix of new compositions and re-working of previously recorded ones including a cover of the Barrett Strong 1959 Motown hit “Money (That’s What I Want)” featuring William Wells on Trombone. The album is a more successful blend of country blues and jazz like the strutting boogie of ‘You’re Wrong’ or the simmering slow blues of the title track ‘It Serves you Right to Suffer.’

The albums sold modestly, and while they garnered critical praise, it didn’t mean a significant expansion of the blues releases at Verve Folkways. Impulse remained, first and foremost, a jazz label, but these albums serve as a compelling reminder that there is no jazz without the blues.

Les Back is a sociologist at the University of Glasgow. He has authored books on music, racism, football and culture, and is a guitarist.

Header image: John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hawkins. Photo: Michael Ochs Archives.