Paris in the 1960s. Jazz was in the air. Pianist Bud Powell was newly resident, having left New York in 1959 to join a community of expat musicians feted by Gauloises-puffing cool cats in black turtlenecks. Drummer Kenny Clarke, Powell’s fellow bebopper, was already based in the French capital, perhaps taking his cue from trumpeter Donald Byrd, who spent several months there in 1958, enjoying stints with his quintet at Le chat qui pêche (The cat who fishes), a club in a cellar in the Latin Quarter. He’d return on and off to Paris for decades. “I have found an audience of connoisseurs who come especially to hear us,” he said. “I’m convinced this has made us play much better.”

For Parisians, jazz was not merely entertainment. It was seen as an art form ranking alongside literature and visual art, linking directly to modern movements championing social justice and civil rights. France’s love affair with jazz might have begun in the 1920s with Joséphine Baker, the US-born singer, dancer and star of the musical “La Revue nègre” at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Baker, whom the French adopted as a national treasure, would go on to live in a chateau in the Dordogne. Visiting the United States in the 1930s, she was refused a hotel room because she was Black.

Jazz generated meeting places along the Rive Gauche, the part of Paris south of the river Seine, for authors, artists and socialites, outliers, insurrectionists and people with ideas. The Harlem Renaissance, that cultural revival of African-American arts and culture, was mirrored in 1920s and 1930s Paris by jazz; Langston Hughes allegedly invented jazz poetry while working as a waiter and dishwasher at Le Grand Duc on rue Pigalle.

Cole Porter came through Paris, as did a young New Orleans clarinetist named Sidney Bechet, eventually so beloved by the French that even after he shot a Frenchwoman while aiming at a musician who’d insulted him, which got him jailed then deported, he was still jubilantly welcomed back post-war to settle in Paris permanently.

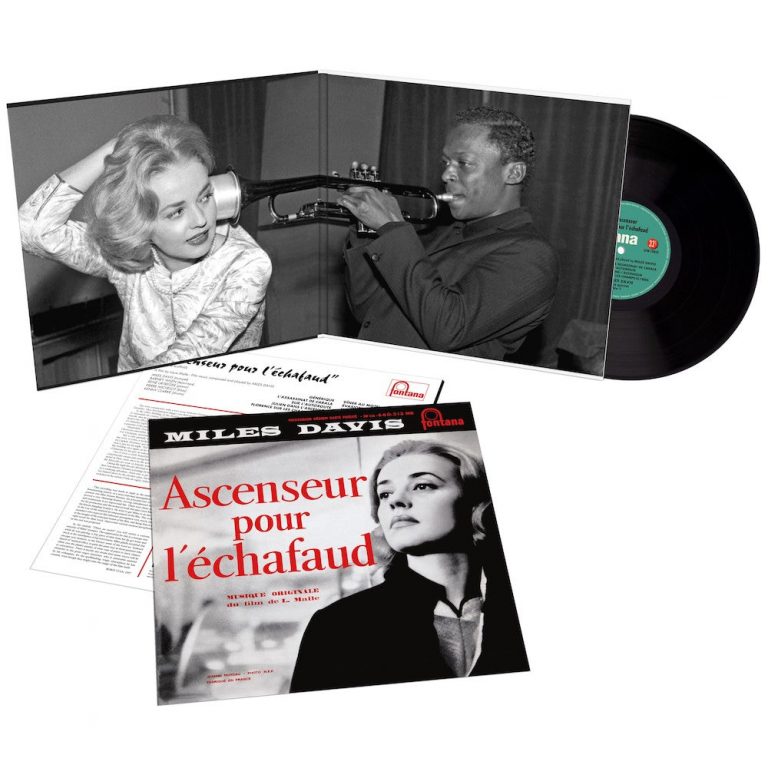

Jazz thrived in the newly liberated French capital. Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker played the inaugural 1948 Festival International de Jazz. A 22-year-old Miles Davis, there with the Tadd Dameron Group, was on the bill in 1949, the year he fell for singer and actress Juliette Gréco, a love affair that continued, intermittently, until the 1960s. Indeed, of all the countries outside the US, it was France that Miles visited the most, recording the soundtrack to, or at least the musical cues for Louis Malle’s 1958 film “Ascenseur pour l’échafaud” (“Elevator to the Gallows”), the year before the oh-so-modal best-seller “Kind of Blue”.

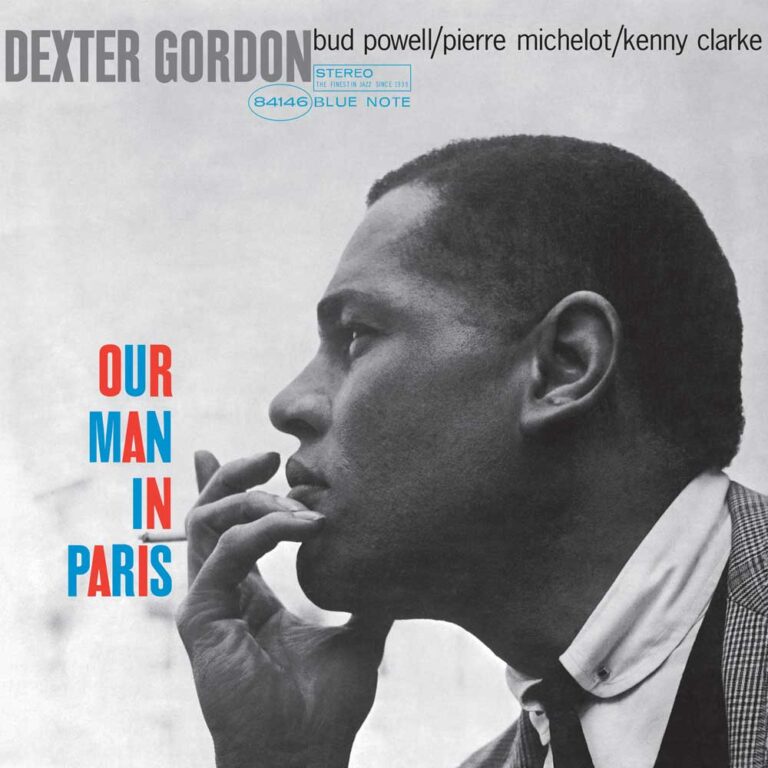

Trumpeter Chet Baker landed in Paris in the mid-1950s, and the capital’s jazz fans stayed loyal to the troubled genius for decades, right into his tender late 1970s musings (check out “Broken Wing (Universal)”, a sung album he cut in Paris in late December 1978). Coleman Hawkins visited multiple times, and made a Paris-themed album – in New York City. Then there was “Long Tall” Dexter Gordon, the rangy tenor player whose substance-battered reputation was transformed after signing to Blue Note in 1960. Of Gordon’s nine studio sessions for the label, 1963’s “Our Man in Paris” (titled after the 1958 Graham Greene spy novel “Our Man in Havana”), is considered his masterpiece.

Gordon, then 40, was living in Copenhagen, and had come over for a day-long session at Paris’s CBS Studios at the invitation of his friend Alfred Lion, Blue Note’s co-founder. Paris locals Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke were there, alongside native Parisian, bassist Pierre Michelot, all of them ready to bebop. Lion’s business partner, Francis Wolff, overseeing, decided standards were the go: Charlie Parker’s “Scrapple from the Apple” – fast, complex, swinging. Ann Ronell’s bluesy “Willow Weep for Me”. A robust take on the Count Basie-linked “Broadway”. A lyrical-as-you-like “Stairway to the Stairs”. A scorching reimagining of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Night In Tunisia”, the closer that clinched the album’s all-time classic status.

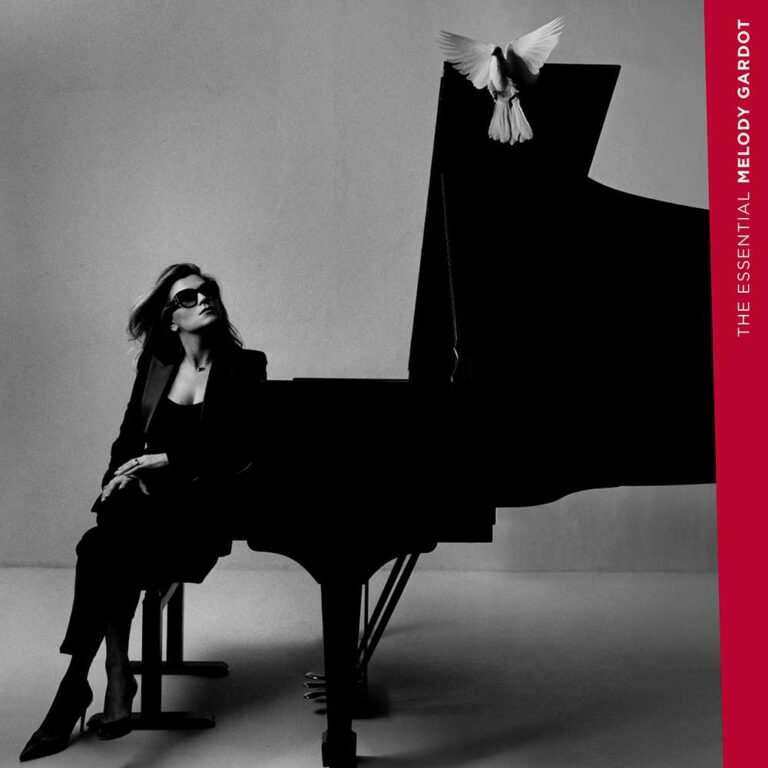

Many an American jazz name has since made their home in Paris. Triple Grammy winner Dee Dee Bridgewater was resident from 1986 to 2010, becoming a French national icon in the process. Singer-songwriter Melody Gardot has lived in Paris for several years now and was awarded the title of chevalier (“knight”) in the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, the country’s top cultural nod, to coincide with the release of her 2022 duet album “Entre eux deux” (“Between Us Two”) with French composer-pianist Philippe Powell. Among the 25 tracks on her current career-spanning “The Essential” are the French-language likes of “C’est magnifique” and “La vie en rose”.

Dexter Gordon happened to receive an officier in the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1986, the year of Bertrand Tavernier’s film “Round Midnight”, in which he stars, magnificently, as a New York saxophonist who moves to Paris in 1959. Dream-like, narratively loose, it is a paean to jazz, to the possibilities offered by this leftfield musical form. It is also, in art as in life, a snapshot of a time when Paris provided a haven for African-American jazz musicians.

Jane Cornwell is an Australian-born, London-based writer on arts, travel and music for publications and platforms in the UK and Australia, including Songlines and Jazzwise. She’s the former jazz critic of the London Evening Standard.

Header image: Paris, France. Alexander Spatari.