With a shared emphasis on improvisation, it was probably inevitable that jazz would be influenced by Indian classical music. After sitar master Ravi Shankar almost single-handedly popularised North Indian classical music in the West – with his debut American concert in 1957, and his first US tour four years later – it wasn’t long before questing jazz musicians began to incorporate elements of Indian music and thought in their own work. Here, we look at some of the jazz-related artists who have contributed to this fertile inter-cultural connection.

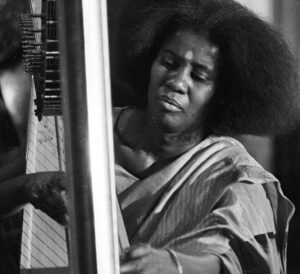

Alice Coltrane

After John Coltrane’s death in 1967, his widow, Alice Coltrane, took his search even further. She became a follower of Indian guru Swami Satchidananda and released a string of albums celebrating her religious devotion, while putting the influence of Indian music front and centre. By the end of the 1970s, she had changed her name to Turiyasangitananda (The Transcendental Lord’s Highest Song of Bliss) and become spiritual director of Shanti Anantam Ashram northwest of Los Angeles.

Throughout the 80s, she concentrated on arranging versions of traditional Vedic chants – or kirtans –which were released as private cassettes, available only to members of the ashram. 1982’s “Turiya Sings” was her deepest cut, with her vocals swathed in Wurlitzer organ and lush synth and strings. “Kirtan: Turiya Sings,” released in 2004, presents a stripped-down mix with synth and strings removed, revealing fragile, transporting hymns of devotion infused with blues and gospel.

ALICE COLTRANE Kirtan: Turiya Sings

Available to purchase from our US store.John Coltrane

The growing popularity of Indian music in the US coincided perfectly with the first stirrings of John Coltrane’s search for both spiritual meaning and a universal musical language that could heal humankind. Indian music and philosophy quickly found a place deep in his heart and, by the beginning of the 1960s, hints of Hindustani music could be heard in his work.

It’s stunningly apparent on the piece “India,” recorded in 1961. With an introductory melody said to be based on a chant Coltrane heard on an album of Indian religious music, it settles into a serene, modal groove with a low rumble reminiscent of the static drone that underpins Indian raga. A version included on “The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings” makes the influence even more explicit, with bassist and oud player Ahmed Abdul-Malik heard at the beginning strumming an Indian tambura before being overwhelmed by drummer Elvin Jones’s muscular polyrhythms.

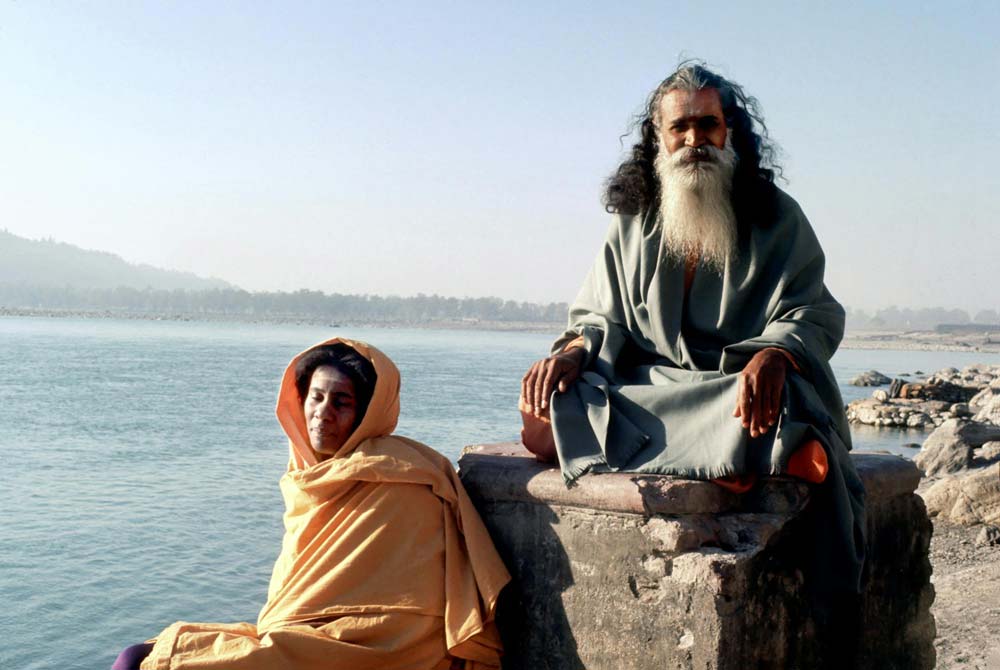

Charles Lloyd Quartet

Saxophonist Charles Lloyd has been a devotee of Indian music and philosophy since seeing Ravi Shankar perform in his student days. By the end of the 60s, he was the counterculture’s jazzman of choice, sharing the hippie fascination with all things Indian. His 1972 album, “Waves,” includes “TM,” a paean to Transcendental Meditation as taught by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and Geeta, from the same year, is a fiery mix of electric fusion and Indian modalities featuring percussionists Aashish and Planish Khan, sons of legendary sarod player, Ali Akbar Khan.

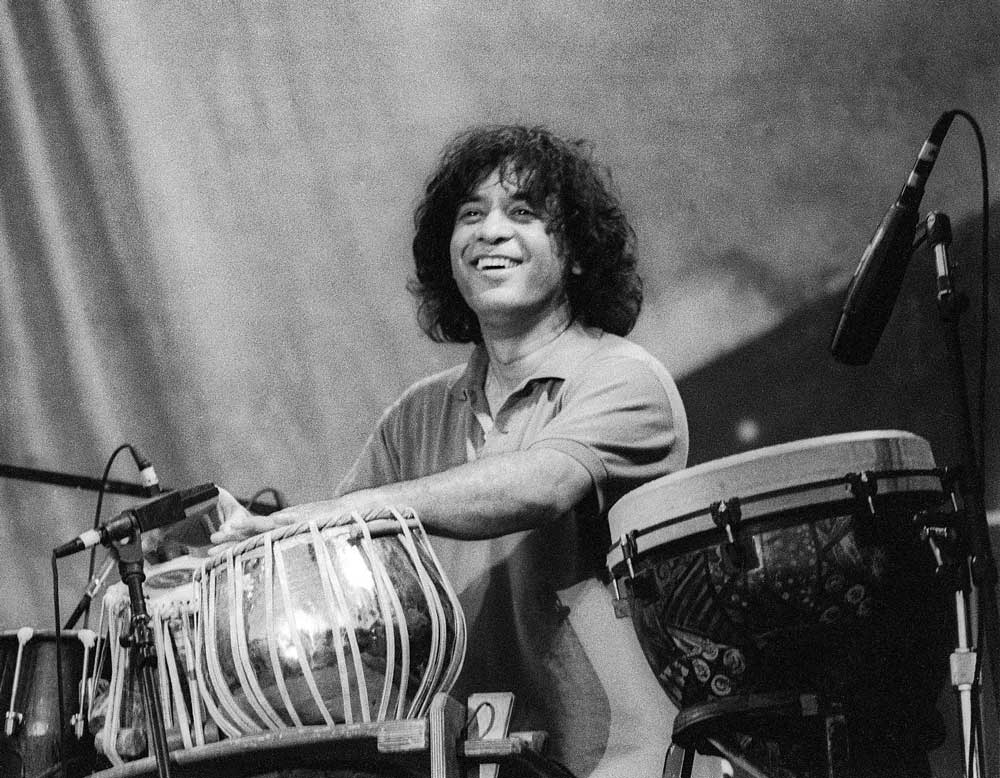

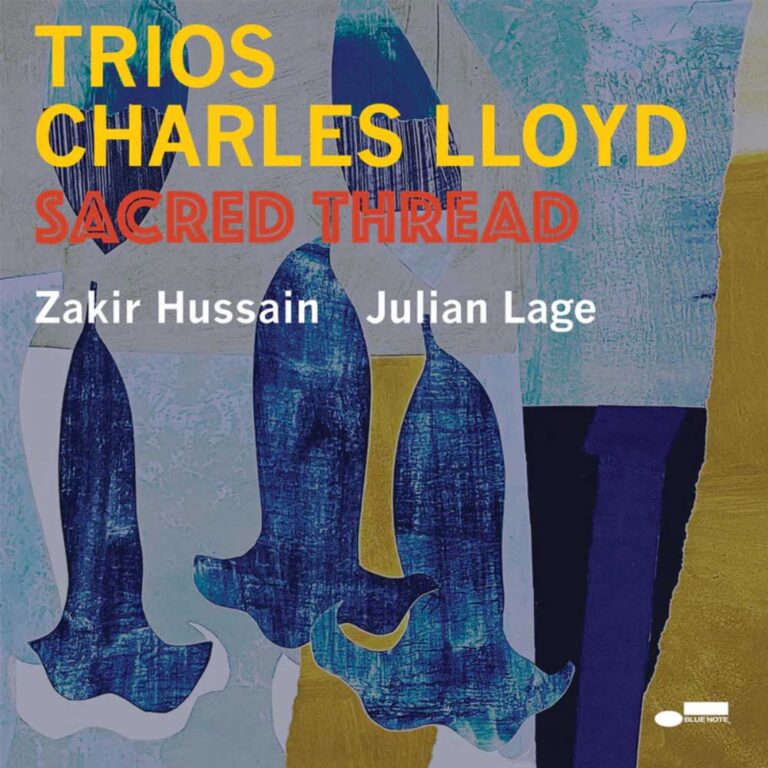

In the 21st century, the Indian influence has remained a vital presence. He’s recorded with tabla maestro Zakir Hussain, on 2006’s “Sangam” and more recently on 2022’s “Trios: Sacred Thread.” On his 2009 album, “Mirror,” he gives full voice to his spiritual beliefs, with the track “Tagi” including a meditative spoken recitation from the sacred Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita.

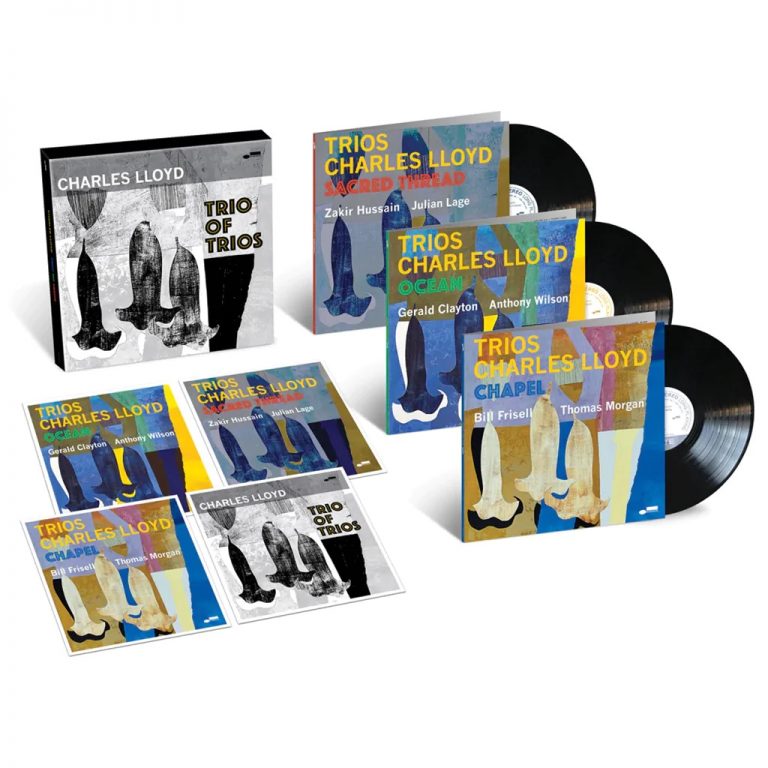

CHARLES LLOYD Trio of Trios

Available to purchase from our US store.

CHARLES LLOYD Sacred Thread

Available to purchase from our US store.Gabor Szabo

Hungarian guitarist Gabor Szabo got his big break playing alongside Charles Lloyd in drummer Chico Hamilton’s quintet from 1961. Like Lloyd, he went on to forge a style that drew on music from outside the conventional jazz canon, arranging well-known tunes and spinning spellbinding solos that incorporated elements of rock, pop, Hungarian folk and Indian classical music.

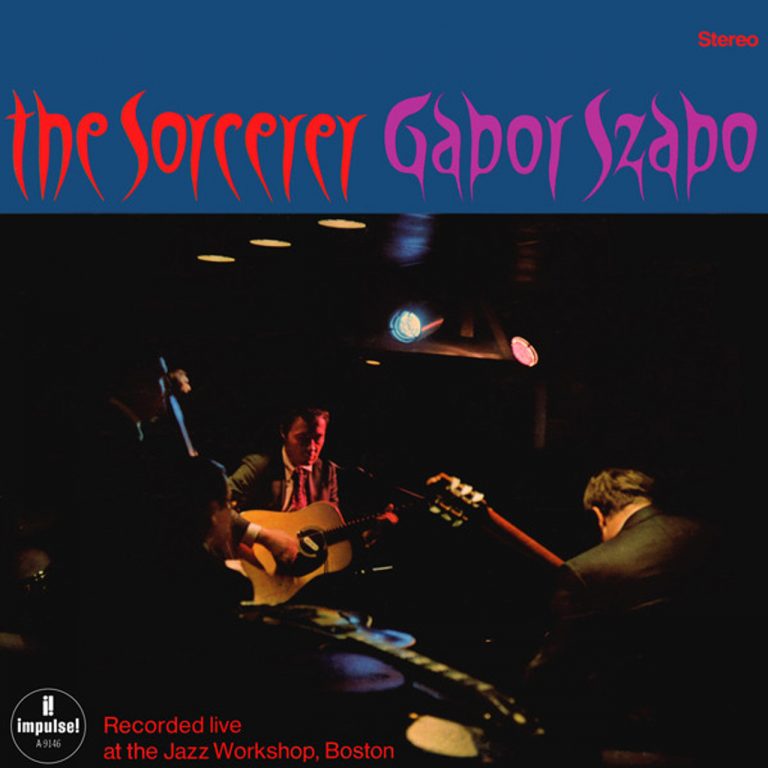

His fascination with Indian sounds abounds on his 1967 album “Jazz Raga” on which numbers like the soul-jazz boogaloo of “Krishna” feature an electric guitar played with a clipped attack resembling a sitar, and tracks like “Ravi” and “Search For Nirvana” have him adding extra colour with an actual sitar. His follow-up album, “The Sorcerer,” released the same year, leans even closer to the east with the track “Space,” which unfolds like a leisurely raga as Szabo and second guitarist Jimmy Stewart trade licks clearly informed by Ali Akbar Khan’s deep sarod meditations.

GABOR SZABO The Sorcerer

Available to purchase from our US store.Arooj Aftab

Born to Pakistani parents and growing up in Lahore, capital of the Punjab province, vocalist Arooj Aftab was influenced as much by Begum Akhtar, iconic singer of Hindustani classical music, as she was by Billie Holiday. After moving to the United States in 2005 at the age of 19, she developed an aesthetic that drew on jazz, minimalism and various styles of Indian and Pakistani music, and scored a major critical hit with her third album, 2021’s “Vulture Prince.”

AROOJ AFTAB Night Reign

Available to purchase from our US store.

Her 2024 release, “Night Reign,” saw her consolidating this approach with a beguiling suite of songs including originals, a version of jazz standard “Autumn Leaves,” and Urdu-language adaptations of poems by 18th century Indian poet Mah Laqa Bai Chanda. Delicate and dreamy, her work brings fresh insight to the enduring and ever-deepening relationship between jazz and Indian music.

Read on…Alice Coltrane – The Artist in Ascension

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Alice Coltrane. Photo: Michael Ochs Archives / Getty.