Ideally, when listening to “Blues Blood”, the new third album by alto-saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, you’ll be cooking. Chopping, stirring and seasoning; slowly turning up the heat. Back in 2021, at the live premiere – online, from a pandemic-struck New York – of this astounding long-form jazz suite, Wilkins and his quartet and a clutch of guest vocalists had a chef working onstage with them. As the music’s meditational tonalities unfurled, the smell of food began to fill the performance space.

“About halfway through I was transported into a totally different place, which is something I’d never experienced before,” says Wilkins, 27, speaking to me from a café in New York City, where he moved in 2015 from Philadelphia to study at Juilliard. “The smell of meals being prepared spoke to an ancestral memory, to the alchemical properties in the music. With this album, I wanted it to feel like you were listening in on an activity, like your mother sharing family recipes with you in the kitchen, or people getting together to feed the pot.”

Billed by Brooklyn arts venue Roulette Intermedium, the project’s commissioners, as “a work that navigates the spiritual and cultural landscape of Black America through long meditations, vamps and multiple modalities”, “Blues Blood” is Wilkins’ most ambitious album yet. Unlike his 2020 debut “Omega” and its acclaimed 2022 follow-up “The 7th Hand”, both largely composed in advance, this recording embraces surrender and unknowability.

IMMANUEL WILKINS Blues Blood

Available to purchase from our US store.Across 14 tracks – including five brief interludes included by Wilkins after encouragement by album producer Meshell Ndegeocello (“she helped me see them as thematic material which married pieces together and served as snatches of memory”) – on-the-fly creation was a given.

Compositionally speaking, Wilkins felt at his most vulnerable. “It was a dangerous space for me. I’m used to having a clear idea of what things are going to sound like when I bring it to the band.” Wilkins has been gigging with pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Rick Rosato and drummer Kweku Sumbry for several years, “but here I left so much open that it almost felt incomplete when we started playing.”

“It did help invite a certain agency among us,” he adds. “So as a jazz composer, it was the right place to be. A dangerous space, with a real surrender to the other musicians onstage.”

The project’s starting point was a quote by Daniel Hamm, one of the Harlem Six, the group of young African American and Hispanic men who were falsely accused of murder in 1964. “I had to open the bruise up and let some of the blues [bruise] blood come out to show them,” stated Hamm, who’d been beaten by prison guards while awaiting trial, and needed to repeatedly request medical attention.

This brutal historic episode previously informed Max Roach’s and Abby Lincoln’s blistering 1960 opus “Freedom Now”, as well as “Come Out”, the famous 1966 piece by Steve Reich. The latter’s use of repetition and layers finds parallels in “Blues Blood”, evolving into something transformational, soothing, often beautiful. It’s an aesthetic in keeping with his penchant for juxtaposition, for finding gold in the margins, for expressing the in-between – all of which, he has said, is at the core of Black existence. And indeed, of jazz music.

“I was thinking about what the blues might mean to jazz and to black music in 2024,” says Wilkins, who was mentored at Juilliard by pianist Jason Moran and trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and has worked as a sideman with musicians from Wynton Marsalis to young vibes star Joel Ross.

“The blues as a feeling has served as a symbol of pleasure in pain for Black folk dating back to work on the plantation. Now it manifests in more elusive ways, and I wanted to write music that made space for people to jam out and make radically different music with the source material.”

Fittingly, each of the four vocalists on “Blues Blood” work across disciplines: Chicago’s Yaw Agyeman. Tamil Nadu-raised, New York-born vocalist Ganavya, her raga-inspired stylings leaping and declaiming. Multi-Grammy-winning Cécile McLorin Salvant, singing “Dark Eyes Smile”, a tune about loved ones becoming ancestors, all soft keys and late-blooming sax lines (“I made so much space for the singers I needed to use the time I had to deliver a profound message”), before joining otherworldly singer-songwriter June McDoom on “Afterlife Residence Time”, the album’s hypnotic lead single.

“On that track I was inspired by Buddhist chanting after doing a retreat in Houston,” he says. “Kweke and Ganavya were there, and people like Shabaka Hutchings and Esperanza Spalding, and every morning Ganavya and Esperanza would chant ‘nam-myoho-renge-kyo’ in a living room which had palpable intensity. The speed and rhythmic commitment to the material got me intrigued.”

The title references a term used in marine biology – that is, how long an element exists in water – as a way of speaking about the transatlantic slave trade. “Salt has a residence time in water of 260 million years. Human blood is salty, so the ancestors who fell or were maybe thrown overboard actually still exist in the Atlantic.”

The body as a vessel is a recurring theme in Wilkins’ work, as it is in the work of multihyphenate Chicagoan and frequent Wilkins collaborator Theaster Gates, who penned the haiku-like lyrics of album opener “Matte Glaze”, which might be about a pot or a body.

“I think about the body as this thing that holds memory, and archives that memory through DNA it then passes it on to our bloodline,” says Wilkins. “In future years I’m always going to be re-investigating the same sort of material from different standpoints.”

Wilkins frequently uses visual art, photography, dance and film to enhance his explorations. Taste and smell are more such aspects, part of his cross-art form arsenal.

“I’m fascinated with the manipulation of thematic material, in confronting painful moments in our history to see what comes out,” he says. “I want to mine its power and emotional energy. To discover if there, in the in-between, in the blues, is the potential to soothe and heal.”

IMMANUEL WILKINS Blues Blood

Available to purchase from our US store.Jane Cornwell is an Australian-born, London-based writer on arts, travel and music for publications and platforms in the UK and Australia, including Songlines and Jazzwise. She’s the former jazz critic of the London Evening Standard.

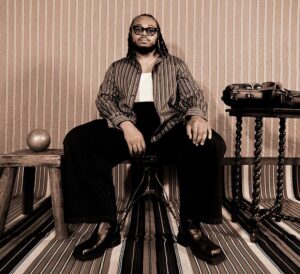

Header image: Immanuel Wilkins. Photo: Joshua Woods (Courtesy of Blue Note Records).