For its first thirty years, Blue Note thrived under the leadership of co-founders Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff alongside legendary engineer Rudy van Gelder. The label had evolved in tandem with its stable of musicians on the cutting edge of jazz – from the hard bop of the late 1950s to the avant-garde abstractions of the mid 1960s.

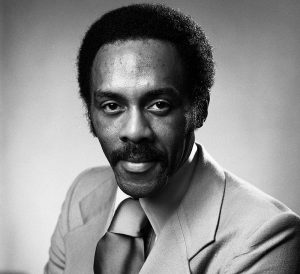

By the start of the 1970s, Blue Note was already navigating new waters, with early jazz fusion excursions such as Donald Byrd’s “Electric Byrd” and Bobby Hutcherson’s “San Francisco.” Both albums were produced by Duke Pearson, but it was the arrival of the six foot tall and debonair George Butler that would transform the sound of Blue Note.

With the passing of Francis Wolff, Butler – who had earned his spurs as a producer for soul and gospel musicians at United Artists Records – was given free rein to release the music he considered relevant for the times. That included albums like Donald Byrd’s “Ethiopian Knights,” a milestone release for the new era of Blue Note. Recorded at Los Angeles’ A&M Studios over two days in August 1971, and featuring a heavyweight group of label stalwarts, the Butler produced session confirmed Byrd’s full transition from hard bop trumpeter to jazz funk pioneer.

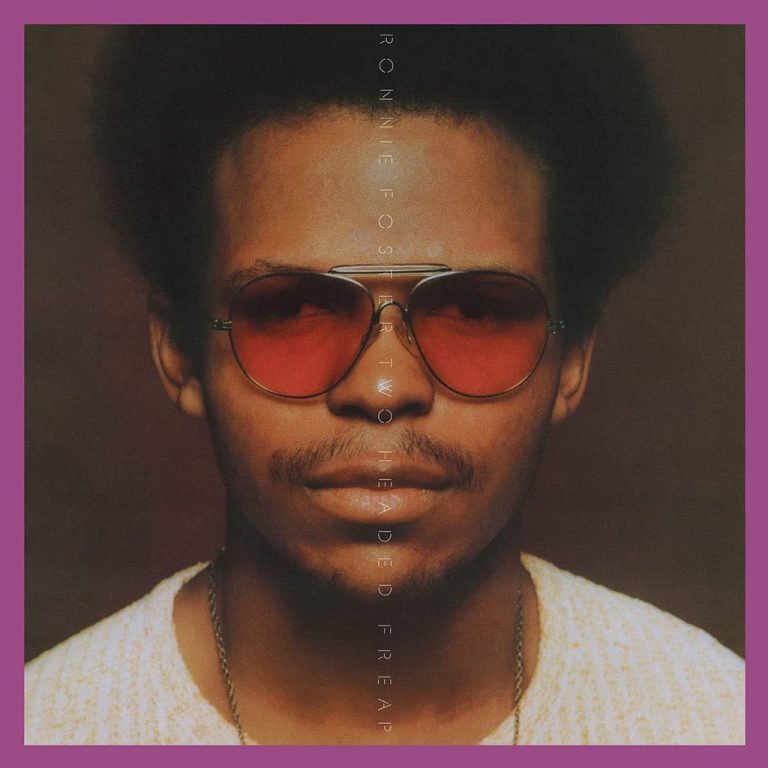

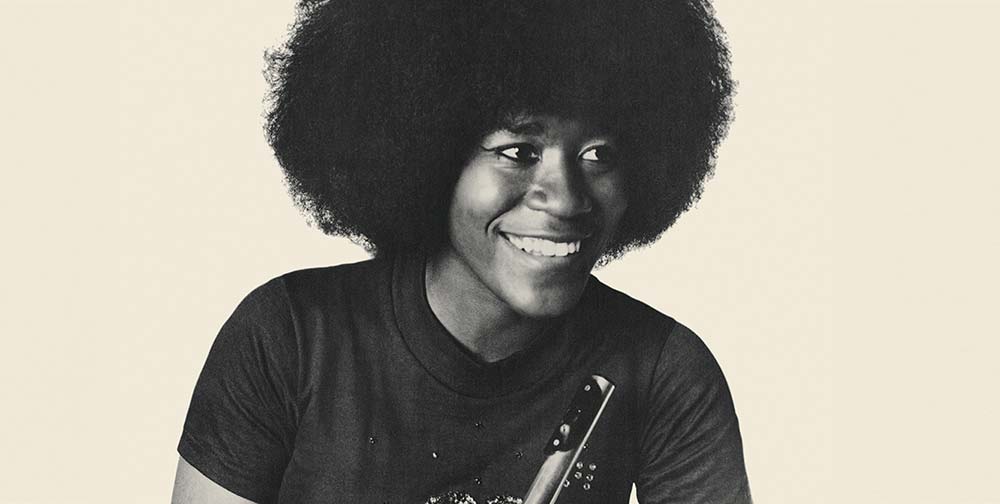

It was quickly followed by Ronnie Foster’s groundbreaking album “Two Headed Freap.” The organist from Buffalo, New York, had previously added a heavy dose of funk to guitarist Grant Green’s soul jazz album “Alive!” from 1970. Foster’s jazz funk classic for Blue Note reached new ears when “Mystic Brew” was sampled by A Tribe Called Quest on their 1993 hip-hop track “Electric Relaxation.”

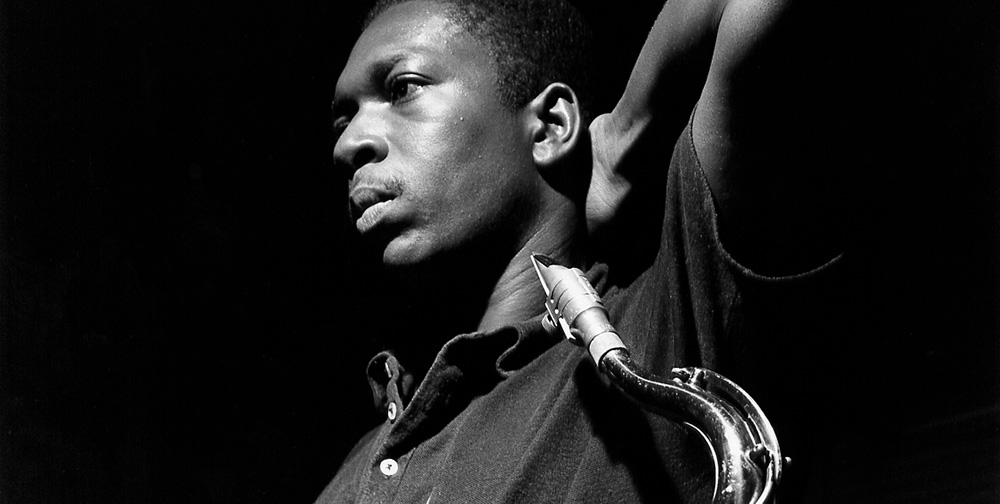

Despite Blue Note continuing to release hard bop by label stalwarts like Elvin Jones, its future was being mapped out by the jazz funk and fusion spearheaded by Donald Byrd. The trumpeter’s recordings for George Butler at Blue Note will forever be associated with the names Larry and Alphonso “Fonce” Mizell.

Fonce Mizell made his name as one of the Motown writing and production team The Corporation, renowned for their work with The Jackson 5; but he left when Berry Gordy’s promises of an album with the brothers never materialised. After buying an ARP Pro-Soloist synthesiser, Fonce and Larry began to create their own demo material which they took to Blue Note under the name Sky High Productions.

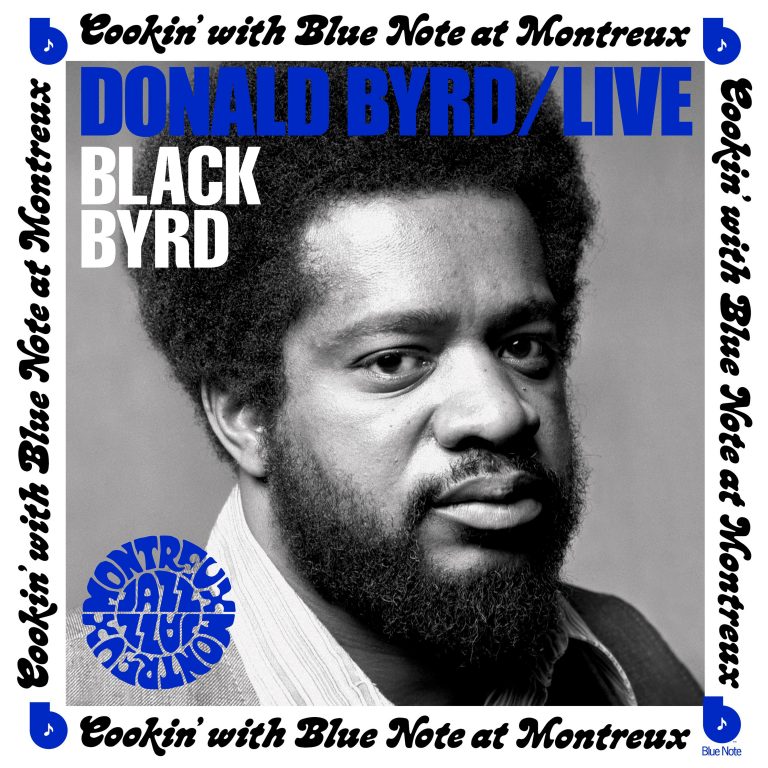

With George Butler moving to the role of Executive Producer for all future releases, the richly layered and spacey Sky High sound came to fruition with Donald Byrd’s jazz funk masterpieces “Black Byrd” and “Street Lady.” They were the first of five scene defining albums the Mizell Brothers wrote, produced, arranged and played on for Byrd at Blue Note between 1973 and 1976.

As well as complex musical arrangements, the Mizell Brothers’ vocal harmonies became an important part of their Sky High sound, which reached its zenith on Donald Byrd’s 1975 album “Places and Spaces.” Veering between heavy space funk and ethereal jazz fusion, the album included Byrd’s biggest hits, the much sampled “Dominoes”, “Change (Makes You Wanna Hustle)” and “Wind Parade.”

The other Blue Note artist most associated with the Mizell Brothers was Texan flautist Bobbi Humphrey. Recorded in the week before Donald Byrd’s “Street Lady” session at Hollywood’s The Sound Factory studio, “Blacks and Blues” moved from soaring soul jazz to electrified funk. The album is best known for the much sampled “Harlem River Drive”, one of the Mizell Brothers most elegant productions.

The following August Humphrey returned to The Sound Factory for the three day session that would become her fifth and final album for Blue Note and the third with the Mizell Brothers. As the title suggests, “Fancy Dancer” was aimed at the feet as much as the head. The album closed with “Please Set Me At Ease” sampled and versioned by Madlib on his 2003 Blue Note album “Shades of Blue,” further proof of the continuing influence of the George Butler era.

While the Mizell Brothers brought a refined studio finesse to Blue Note, George Butler never lost his love of live jazz. In July 1973, he took several of Blue Note’s stars to the Montreux Jazz Festival for a famous label showcase. All of the concerts were recorded as part of the “Cookin’ With Blue Note at Montreux” series. However, the Donald Byrd concert recording languished in the Blue Note vaults until 2022. Stripped of the Mizell production polish, the 10 piece band (including Larry and Fonce Mizell) presented classics like “Black Byrd” in their rawer, funk driven form.

For someone so connected with the jazz funk era it’s perhaps ironic that George Butler would become best known for steering the career of resolutely be-bop purist Wynton Marsalis in the early 1980s while at Columbia (after leaving Blue Note in 1978). In the process Butler helped change the course of jazz yet again as he had done at Blue Note more than a decade before.

Andy Thomas is a London based writer who has contributed regularly to Straight No Chaser, Wax Poetics, We Jazz, Red Bull Music Academy, and Bandcamp Daily. He has also written liner notes for Strut, Soul Jazz and Brownswood Recordings as well as storyboards for short films at RBMA.

Header photo: Don Hunstein/Sony Music Entertainment