In 1964, tenor saxophonist Stan Getz was riding his second great wave of hip insouciance. A decade earlier, during the mid-to-late 1950s, he’d been a key figure in the West Coast cool jazz scene, along with the likes of Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker, offering a laid-back, sun-kissed alternative to the urban muscularity of hard bop. Then, in the early 1960s, he was instrumental in spearheading the runaway success of bossa nova in the US, bringing the mellifluous chime of this relaxed Brazilian samba style to American audiences hungry for novelty.

Getz’s first foray into bossa nova was 1962’s “Jazz Samba”, recorded with guitarist Charlie Byrd, which featured a cover of “Desafinado” by leading Brazilian composer and arranger Antonio Carlos Jobim. After this became a million-selling hit, Getz quickly recorded a handful of other bossa nova titles. He was onto something.

His most notable date in this vein was “Getz/Gilberto”, recorded in 1963 with a crack squad of Brazilian musicians including Jobim on piano and, taking equal billing, the guitarist, singer and composer João Gilberto – known as the father of bossa nova – who had pioneered the music back home in Brazil in the late 1950s. It was during this recording session that fate stepped in. Gilberto’s 22-year-old wife, Astrud, happened to be in the control room and, though not a professional singer, she was encouraged to provide the vocals for a recording of a song written by Jobim and lyricist Vinicius de Moraes. The tune was “The Girl from Ipanema” and Astrud Gilberto’s shy, innocent and sweetly unaffected vocals struck a resonant chord with audiences, turning the recording into a huge international hit when it was released in May 1964 and fully catapulting the bossa nova craze into the public consciousness.

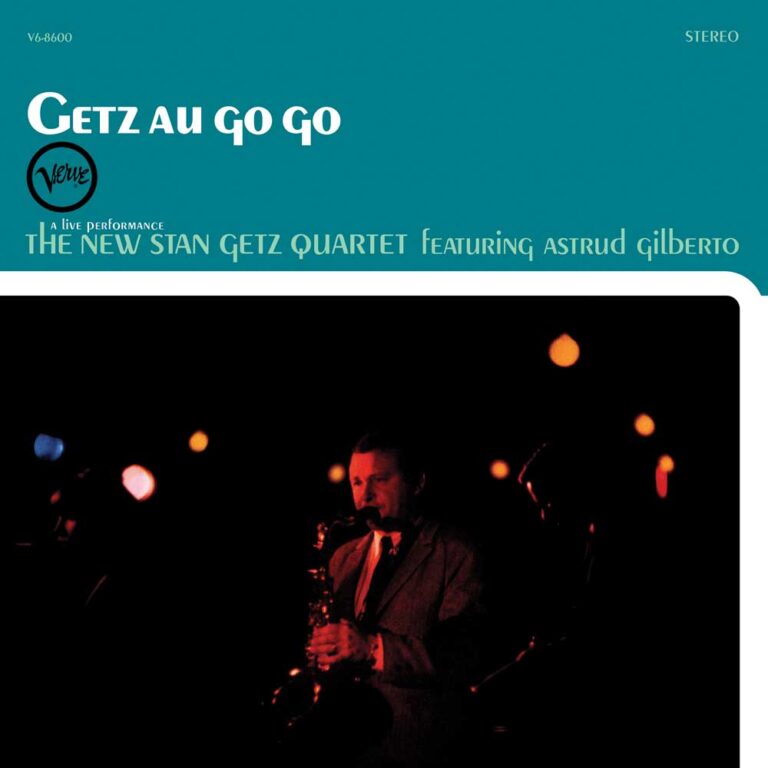

Recorded just a few months later, “Getz Au Go Go” finds Getz teamed once again with Astrud Gilberto, with the young singer at the height of her new-found fame. Six of its 10 tracks were recorded live at the fashionable Greenwich Village club Café Au Go Go in August 1964, the remainder two months later in the far grander surroundings of Carnegie Hall. Getz and Gilberto are backed by a band working under the name the New Stan Getz Quartet with the young Gary Burton – just 21 years of age – on vibraphone, Kenny Burrell on guitar, bass duties split between Gene Cherico and Chuck Israels (then a key member of Bill Evans’ trio), and drums shared by jazzer Joe Hunt and Brazilian bossa nova drummer Helcio Milito. There’s a crackling energy about the whole deal, the sound of artists entirely capturing the moment.

Gallery Photos: PoPsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Of course, there are plenty of bossa nova tracks, capitalising on the exotic zeitgeist. Jobim’s “Corcovado (Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars)” has Gilberto crooning gently in both English and Portuguese while Getz embellishes with a deeply warm and luxuriant tenor. “Eu e Vocé ” is a nippy jaunt with Gilberto negotiating tongue-twister vocals and Kenny Burrell adding authentically Brazilian acoustic guitar stylings. And Jobim’s “One Note Samba” is bossa at its smoothest, propelled by Joe Hunt’s clicking rim shots. Other compositions are given a bossa treatment, such as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic from the Great American Songbook, “It Might as Well be Spring,” which features Gilberto at her most wide-eyed and little-girl-lost, contrasting neatly with Getz’s gorgeously poised and assured soloing. It’s an inspired meeting of innocence and experience.

On the instrumental numbers where Gilberto sits out, the New Stan Getz Quartet lean closer into jazz, revealing a sprightly yet authoritative ensemble. The standard “Here’s That Rainy Day” is given a dreamy reading with Burton’s vibes swelling like a thick eiderdown, cushioning Getz’s sleepy lyricism while the rhythm section gently rocks. Gershwin’s “Summertime” is stretched out to a sultry eight minutes over a louche chordal bass figure, unobtrusively swinging drums, the vibes shimmering like a thick heat haze and Getz lazy and cool like the Mississippi in August. Elsewhere, Burton steps up as a quirky and original composer. His tune “The Singing Song” is a glistening curio – both cool and weird like a highly polished jewel – with clip-clop percussion, sneaky midnight vibes and Getz blowing with surprising heft in lugubrious lower registers.

In the years that followed, Gilberto would go on to enjoy a long career and much adoration as the definitive voice of bossa nova. Burton would emerge as an innovative vibraphone stylist and a pioneer of jazz fusion. Getz had just one more recording to make in his bossa period – the live album “Getz/Gilberto Vol. 2” (recorded in 1964 and released two years later), which reunited hm with João Gilberto – before moving on to deeper jazz and even exploring fusion with Chick Corea, Stanley Clarke and Tony Williams. But, for those with ears to hear, “Getz Au Go Go” stands as the perfect snapshot of a pristine and beguiling musical moment.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a biography of saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Vibraphonist Gary Burton, jazz singer Astrud Gilberto, bassist Gene Cherico and saxophonist Stan Getz perform onstage at Birdland on the day they recorded the live album Getz Au Go Go on August 19, 1964 in New York. Photo: PoPsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.