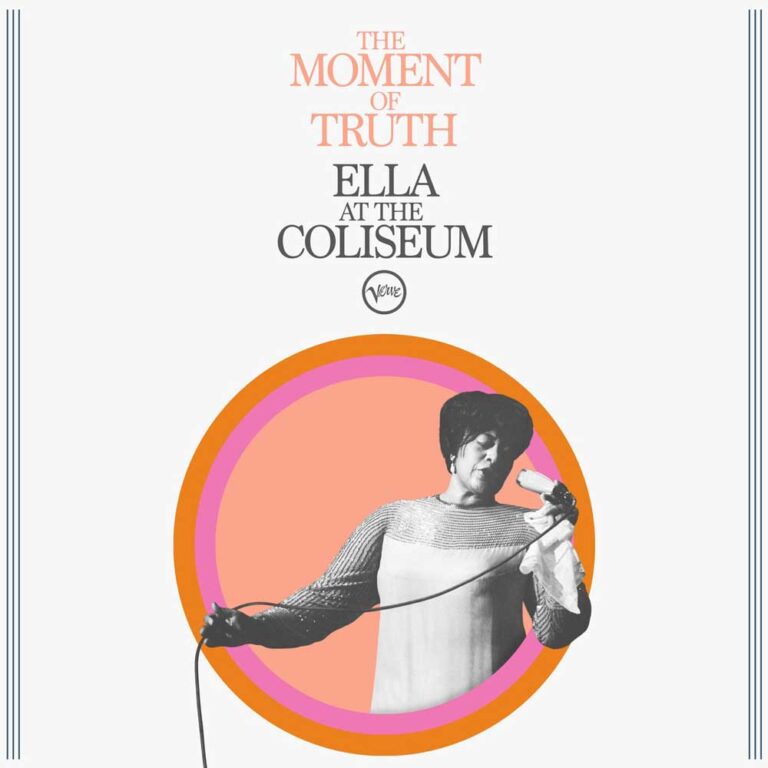

This piece is from the liner notes from the never before released “The Moment of Truth: Ella at the Coliseum.”

With thanks to Verve Records

Ella Fitzgerald virtually invented the live album and, appropriately, there are more concert recordings of her that have been both officially and unofficially released than practically any other artist, ever—major or minor, male or female, jazz or whatever. And with good reason: every time a new Ella concert tape is unearthed, she never disappoints. There was never a moment when she was not doing her absolute best work and she never seems to have experienced what other performers would consider “an off night.” In a sense, for Ella Fitzgerald, every night was The Moment of Truth.

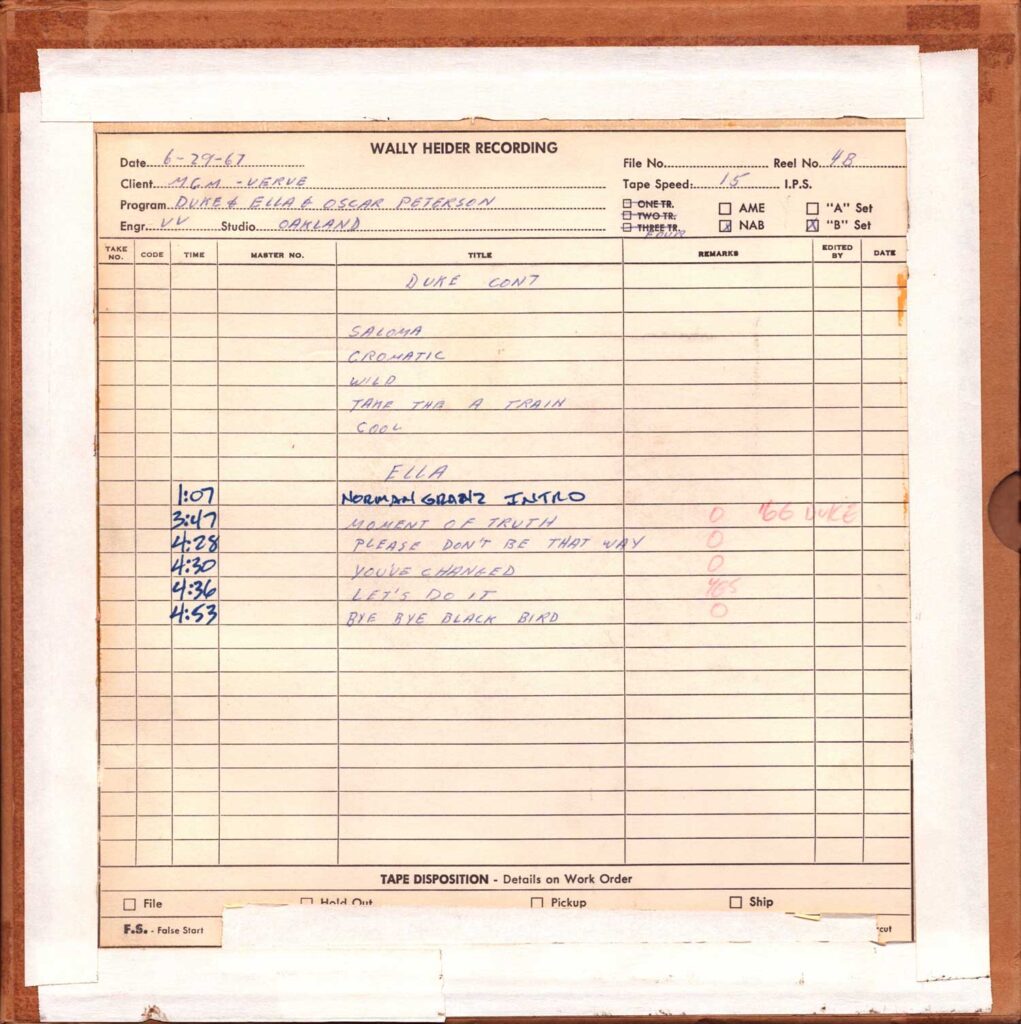

This previously unknown concert from the summer of 1967 finds Ella Fitzgerald in a particularly interesting place. A year earlier, she had concluded her ten-year relationship with Verve Records, the label essentially created expressly for her. At the same time, she was in the middle of an especially rewarding collaboration with Duke Ellington that would run fairly consistently from 1965 to 1968. And while she was nowhere near the end of her partnership with personal manager and producer Norman Granz, the two were at a unique crossroads together.

In July 1966, Fitzgerald would make “Whisper Not”, her final studio album for Verve. And although Granz continued to manage her tours and concert appearances, they would not make a new album together for over five years, until 1972.

Ella and Ellington had spent much of 1966 touring together, starting the year in Europe, as documented by the famous Stockholm concert (released by Pablo Records in 1984) from February. Over the summer, they would give us an even more tangible document of their collaboration at the Antibes Jazz Festival at the end of July 1966, as captured in the epic eight-CD package “The Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington Côte d’Azur Concerts on Verve”, released in 1998.

There are concerts recorded at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles, Fitzgerald’s longtime city of residence, from September, and then in January 1967 they made yet another tour of Europe. Back in the states, the Ella–Ellington combination was at the center of a series of concerts taped at Carnegie Hall (March) and the Hollywood Bowl (June and July) that were released after Duke’s death, in 1974, as “The Greatest Jazz Concert in the World.”

This Oakland concert occurs in between two dates at the big Bowl in L.A. Granz was never stingy with talent—this was a typically spectacular and generous offering, one that could easily fill an entire arena—a set by the Oscar Peterson Trio, followed by one from Duke Ellington and his Orchestra and, lastly, Ella Fitzgerald both with her own trio and with the full Ellington orchestra. There also, apparently was an all-star combo featuring Coleman Hawkins, Zoot Sims, Benny Carter and Clark Terry, presumably playing with Peterson’s trio.

Although Tommy Flanagan served as Ella’s pianist and musical director for most of the 1960s and ’70s, during the years of the Ellington tours (1965–1968), her customary accompanist was Jimmy Jones, who’d already worked extensively with Sarah Vaughan, among many others. Her bassist that year was the remarkable and young Bob Cranshaw, who’d already proven his worth with Sonny Rollins as well as on dozens of classic hard bop sessions. Ellington’s longtime drummer, the formidable Sam Woodyard, doubled in that capacity with Fitzgerald on these concerts.

If there’s a disappointment in this performance, it’s that Ellington himself doesn’t play at all; on most of their other personal appearances together, he generally joins her for a few tunes, usually on at least one of his own. But if there’s a compensating virtue, this concert is full of contemporaneous pop songs that were only briefly in Ella’s concert book and that she never officially recorded—and that she sings spectacularly well. (As far as we can tell, all the arrangements for these were by Jones.)

She starts with one of these “new things” as she puts it, “The Moment of Truth,” an excellent opener if ever there was one. She learned the song, by the lesser-known composer Frank Scott with the arranger and trombonist Tex Satterwhite, from Tony Bennett, who’d first recorded it in 1963 and since then had sung it on many a TV variety show; Ella herself sang it on The Danny Kaye Show in October 1966. You can feel the crowd’s enthusiasm even before Fitzgerald starts singing, even as we hear Woodyard’s cymbals setting up her entrance. “The Moment of Truth” is ‘Sinatra-for-Swingin’-Lovers’ opus of the kind that Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen famously wrote for Frank, in the same vein as “The Tender Trap” and “Ring-a-Ding-Ding.”

She slows down—the tempo and Jones’s slinky vamp prompt her to declare, “You thought I was going to do a striptease!” She then addresses a latecomer in the house, “You missed the first song!” The 1934 hit “Don’t Be That Way,” takes her back to her Chick Webb days, when arranger-composer Edgar Sampson was writing for the orchestras of both Webb and Benny Goodman, who introduced his version at the epochal 1938 Carnegie Hall concert. Fitzgerald herself first sang Mitchell Parish’s lyric in 1957 in her first album with Louis Armstrong; her reading here is slower and bluesier than most of the big band performances, but irresistibly swinging.

She gets slower still with a very sad ballad, the 1941 “You’ve Changed” by Carl Fischer—later better known as Frankie Laine’s musical director—which remains the only major standard by lyricist Bill Carey. Fitzgerald makes the most of the song’s descending lines, famously recorded by Billie Holiday on “Lady in Satin”, and her reading is no less devastatingly moving.

Fitzgerald gets much more sensual and playful on “Let’s Do It,” the all-time Cole Porter classic, from the 1928 Broadway show Paris. She first sang this on her beloved 1956 “Cole Porter Songbook,” and it was frequently in her book during the Ellington tours. She starts with the verse, which has melodic parallels to the 1923 pop song “My Sweetie Went Away,” famously recorded by Bessie Smith, as well as to Lester Young’s famous solo on “Sometimes I’m Happy.” Fitzgerald stretches Porter’s tune out gloriously, from that verse to multiple choruses of one of one of his quintessential list lyrics; she extends it not only with a funky original melody line but self-penned references aplenty to pop culture figures like “The Beatles, The Animals, Sonny and Cher” as well as “Richard and Elizabeth” (Burton and Taylor) as well as “James Bond 007.” Porter, who’d died in 1964, was in no position to object, but I can’t imagine that he wouldn’t have loved it.

“Bye Bye Blackbird” begins with, apparently, someone in the audience offering her a drink; she responds by saying, “I don’t dare drink, somebody might think that I’m Dean Martin’s sister!” Some possibly obvious context: Fitzgerald was indeed a frequent guest on The Dean Martin Show during this period. A few seconds later, we hear an off-mic male voice (probably Jones) saying something. She then giggles as she continues, “Something new has been added to the act. That’s what you get for working with Dean!”

“Blackbird” is the kind of venerable 1926 standard that jazz singers like Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan routinely included in their sets, but many just kind of ran through it and essentially threw it away as a quick “chaser.” Fitzgerald, conversely, lingers on “Blackbird” and sings it like she means it; as much as she loves being on the road and singing in glorious venues like the Coliseum, she values being home with her loved ones, especially her son Ray Brown Jr. She emphasizes the first note of every eight-bar section, “Packed up all my cares and woes…” “Where somebody waits for me…”; the second chorus has her getting yet more spontaneous, omitting sections and changing words at her discretion, “so bird, get lost!” The third chorus is mostly scat, and encompasses an even more expansive rewriting of the melody, stretched out for dramatic purposes. She exclaims, “Hey, baby, I found me a good one!”

Alas, Fitzgerald sang only a few songs by one of the major hit-making teams of the era, Burt Bacharach and Hal David; there are wondrous concert recordings of “Wives and Lovers” (Stockholm, 1966) and “A House Is Not a Home” (Montreux, 1969) among others. This is the only documented recording of Fitzgerald performing what might be Hal and Burt’s greatest love song, and it was worth waiting for: “Alfie” is one of her most stunning, heartfelt ballad readings ever, further establishing that as a singer of love songs and torch songs, Ella was in the same class as her contemporaries Holiday and Sinatra whenever she wanted to be. If only Granz had seen fit to produce Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Bacharach–David Songbook — which would also have been far superior to any of the non-Norman albums she was making in this period for Capitol Records. She starts this exceptional track by saying quietly to the house tech guy, “Sexy lights, dear.”

“Alfie” is the first of several songs here which includes a famous Fitzgerald device — one she employed more and more as the ’60s led into the ’70s — a detour in the coda, in which she takes a left turn through another song before arriving at the conclusion. Here it’s “You’re Nobody ’til Somebody Loves You.” As she hits the final notes, some enthusiastic fan in the house shouts his approval vociferously: “If you love this, clap!” We can’t help but agree with him — I find myself clapping all alone in my uptown apartment in 2024 — and it causes Fitzgerald to chuckle as she offers her thank yous.

“In a Mellow Tone” is the Ellington jam session standard with lyrics by her longtime producer and friend Milt Gabler. There’s the expected scat solo in the second chorus, and here more than elsewhere, it illustrates Fitzgerald’s love for dancing. Her improvisations here are nothing if not verbal terpsichore, she scats with more pure feeling and sheer energy than most singers put into actual words. Let it be known that Ella Fitzgerald takes nothing for granted, not even nonsense.

As with “Alfie,” this is thus far the only known instance of Fitzgerald performing the 1966 Bob Crewe hit “Music to Watch Girls By”— a song that most of us assume is by either Bacharach, Herb Alpert or both, but is actually the work of the lesser-known Sid Ramin. Andy Williams popularized the lyrics by Tony Velona, but, with no disrespect to the latter, no one sang it with more energy and even passion than Fitzgerald. It’s one of many examples of Fitzgerald from the 1930s to the 1990s taking a piece of music and making it into something more than it was. And there’s a particularly joyful detour here, through Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “Happy Talk,” which she had recorded in full back in 1949 when South Pacific was new.

She concludes the concert with “Mack the Knife.” After giving her all for the whole show thus far, you would think Fitzgerald would be exhausted, but she’s still fresh as a daisy as she launches into the highest energy number yet. When Fitzgerald gave us her iconic performance of that 1928 Berlin theater song live in Berlin in 1960, some listening to the live recording assumed that she’d only pretended to forget the lyrics so she could make a show out of improvising new ones. Well, the mistake was, as far as we can determine, completely genuine, and the remarkable stagecraft no less so; at least there’s no evidence of any other concert where she forgets the words. By 1967, she was singing the song with full-on big band accompaniment; Fitzgerald’s version doesn’t include the relentless modulations of Bobby Darin’s blockbuster single, but there’s no shortage of excitement, including affectionate references to Darin and her loving homage to Louis Armstrong.

At the end of the concert, it’s Norman Granz, in his closing announcement, who sounds tired, not Fitzgerald. Ella was probably grateful that because she was part of this huge all-star package in a stadium, she wouldn’t have to do a second set, as she would have been expected to do in a club. Actually, she sounds like she’s rarin’ to go, as if she could have easily gone on singing another 15 songs over another hour or more — and it would have been just as great.

Like we said, this was the moment of truth for Ella Fitzgerald, but, then again, every night was.

Will Friedwald is the author of nine books, including A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers; Stardust Melodies: The Biography of Twelve of America’s Most Popular Songs; Jazz Singing: America’s Great Voices from Bessie Smith to Bebop and Beyond; Sinatra! The Song Is You; and Tony Bennett: The Good Life (with Tony Bennett).

Header image: Ella Fitzgerald. Photo: Photopress Archiv / Keystone / Bridgeman Images.