Jackie McLean’s “Demon’s Dance” is the culmination of one of the most astonishing creative streaks in the history of jazz. Recorded in 1967 (though not released until 1970), it was the last of more than a dozen albums the alto saxophonist recorded for Blue Note as a leader after signing to the label in 1959. Yet this extraordinary run of albums might never have existed if it hadn’t been for a stroke of bad luck. By 1957, McLean had been using heroin for nearly a decade, during which time he’d been arrested several times and even briefly jailed for possession. As a result, his cabaret card was revoked, making it illegal for him to perform in New York City clubs. Robbed of the chance to earn a living playing live, he turned to the studio, cutting a dizzying number of dates, first for Prestige and then for Blue Note.

McLean’s intensive output during the 1960s allowed him to evolve rapidly as an artist. At the beginning of the decade, he was still firmly rooted in the hard bop school, with a strong stylistic debt to the bebop of Charlie Parker. By 1962’s “Let Freedom Ring,” however, he’d already begun to incorporate ideas from modal and free jazz. Fast forward to 1967 and his “New and Old Gospel” featured Ornette Coleman on wildly unschooled trumpet, while “‘Bout Soul,” cut the same year, was a daringly avant-garde offering, featuring drummer Rashied Ali, fresh out of John Coltrane’s fiery final band, supplying omnidirectional polyrhythms.

Given that trajectory, “Demon’s Dance” represented something of a step back from the precipice, turning again to a driving hard bop aesthetic. For the date, McLean called on the talents of pianist LaMont Johnson and bassist Scotty Holt, frequent collaborators who had both played on “New and Old Gospel,” and drummer Jack DeJohnette who’d made a name for himself with saxophonist Charles Lloyd. The quintet was rounded out by young hard bop trumpeter Woody Shaw who’d already made classic Blue Note dates with Horace Silver and Larry Young but had yet to release a session as a leader.

The album’s undoubted highlight is its opening title track, a McLean original. After a peremptory horn fanfare, a grinding 6/8 bassline and restlessly crashing drums set a tone of dark menace. Yet, from its very first notes, McLean’s solo instantly switches the mood to one of joyous exultation, as he crests in repeated waves of yearning beauty, backed by DeJohnette’s huge, Elvin Jones-like rolls and swells. It’s an utterly intoxicating performance and a pinnacle moment in McLean’s discography. It’s followed by trumpeter Cal Massey’s wistful ballad, “Toyland,” in which McLean’s playing is both grounded in tradition and given to sudden, unexpected spurts and flurries. Johnson shines here too, with a gorgeously delicate solo for the ages.

From there, the album strikes out purposefully into hard bop territory, beginning with two muscular Shaw compositions: the up-tempo romp of “Boo Ann’s Grand” and the breezy bossa nova of “Sweet Love Of Mine.” On both of these, McLean luxuriates masterfully in the language he’d developed over the previous decade – unmistakably piquant, detailed and urgent. Shaw also shows his considerable chops, with solos tuneful and precise, full of rich buzzes and growls, proposing a neat balance of abandon and control. The final two tracks turn the heat up even more. McLean’s “Floogeh” is crazily fast be-bop with an intricate head and McLean nodding reverently to his hero Charlie Parker with a furious, scalpel-sharp solo. To conclude, another tune by Cal Massey – “Message From Trane” – pays tribute to the recently departed John Coltrane, with a big-hearted heavy-swinger providing DeJohnette with the opportunity to take a satisfactorily boisterous solo.

It’s only right that “Demon’s Dance” feels like a summation of everything McLean had achieved up till then. It marked the end of both his exceptionally fertile time at Blue Note and his youthful prime. Turning instead to touring and beginning a long career as a respected educator, he would not record again for another five years. But he’d already done enough to secure his place in the eternal pantheon of true jazz greats.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

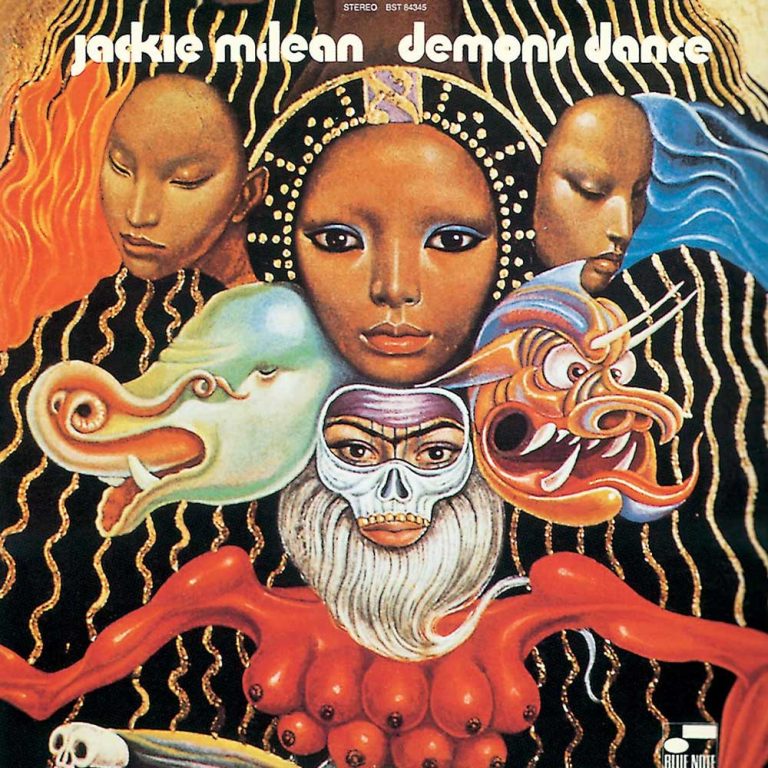

Header image: Jackie McLean. Photo: Francis Wolff/Blue Note Records.