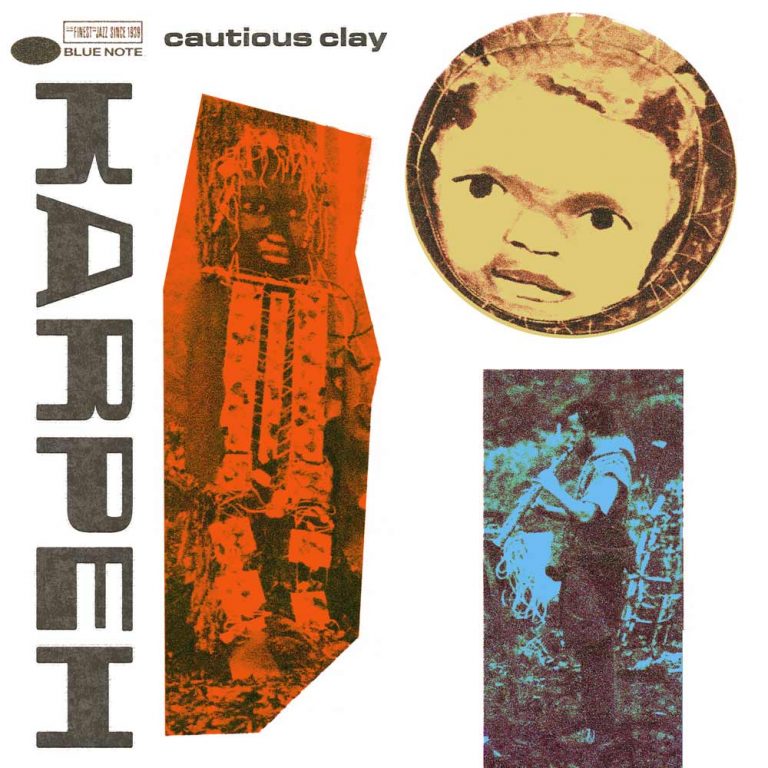

Here’s the thing about Cautious Clay’s new album “Karpeh”: though it’s out on Blue Note Records, and you’re reading about it on a site called Everything Jazz, it’s not really a jazz album. There are elements, sure, but “Karpeh” synthesises funk and soul for a sound that’s neither exclusively. With its big drums and deep groove, it’s better suited for a drive along the PCH than a small supper club in Greenwich Village. That was done on purpose. Clay, a multi-instrumentalist born Joshua Karpeh whose previous album scanned as R&B, wanted a nuanced portrayal of his family history.

Cautious Clay Karpeh

Available to purchase from our US store.“I wanted to call it a jazz album, but I also just wanted it to be an experimental album, a little bit more of a concept album,” Clay says on a video call from New York. “I’m very aware that it’s not jazz in the jazz tradition. There’s a lot of experimental stuff on this album that I felt I needed to contextualise, because the process was very different for me.”

Artists like Clay seek to redefine what the genre can entail. While “Karpeh” largely eschews the traditional aspects of jazz, the genre itself was never meant to stay in one place for long. The best example of its evolution can be heard in the music of Miles Davis, who shifted the course of jazz at least twice – from hard bop to broader improvisation on “Kind of Blue;” to an ambitious blend of funk and psych-rock on “Bitches Brew”.

In the 2000s, the pianist Robert Glasper and the trumpeter Roy Hargrove blended jazz, rap and neo-soul, which ushered a new wave of musicians who didn’t just sample the old stuff; they created their own source material. Clay is in the lineage of these players – expectations don’t apply to this work. “I wanted to be able to say, ‘Look, this is a little bit more,’” he says of “Karpeh”. “I want to be able to preface this in a way where people don’t have a limited scope.”

“Karpeh” details Clay’s family history and his last name in an efficient 42-minute set unfolding in three acts. “The name had a lot of significance from the fact that it’s my mother’s maiden name, but it’s also an African name that stems from my grandfather,” a member of the Kru tribe in Liberia, he says. “I felt that played into what I wanted to portray symbolically with the album, of both sides of my family being immigrants, but then also both sides of them being African-American in some contexts.

“So it’s really unpacking three generations of experiences from both sides of my grandparents, down to my parents and then down to me,” he added, “and how I translate conceptions of intimacy and the importance of solitude as well.”

Through songs like “Fishtown,” “Ohio” and “The Tide Is My Witness,” the first section depicts his upbringing in Cleveland and his desire to live abundantly. In the second act, on tracks like “Another Half” and “Glass Face,” he details his experience with psychedelic drugs and how they helped him self-reflect and foster deeper connections with others. By the time the third act, and songs like “Yesterday’s Price” roll around, Clay revels in solitude as a form of self-care. “Unfinished House,” in particular, is about the house his paternal grandfather started building in Washington that never got finished. It doubles as a metaphor for the complicated relationship he had with his wife and seven children. “There was an element of narrative going on around this house, the relationship that my grandparents had in that house, and how that relationship affected the current state of the house,” Clay says. “So that’s the narrative I’m telling on that side of the family, whereas the Karpeh side is very much grounded in the name and the cultural identity of the name.”

Ultimately, “Karpeh” isn’t just a personal record, it’s a nuanced portrayal of family dynamics to which everyone can relate. It’s real life unfiltered.

“I want it to represent a piece of American history,” he says broadly. “I wanted to be specific on this album to demonstrate the historical significance of my family and my experiences. It’s a way for me to encourage people to look within themselves, to do some internal work to demonstrate what we can all overcome or apply differently in our own lives.”

Cautious Clay Karpeh

Available to purchase from our US store.Marcus J. Moore is a music journalist who co-leads the jazz series “5 Minutes That Will Make You Love…” at The New York Times. His coverage can be found at NPR, Pitchfork, Time, Entertainment Weekly, GQ, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, and The Atlantic.

Header photo: Blue Note Records