Created during a time when photography was still striving to be seen as ‘art’, Wolff’s use of stark contrast and abstract framing echoes other 20th century artists such as Man Ray, and Horst P Horst.

Walking this line between art, documentary and marketing, Wolff produced an exquisite body of work for Blue Note Records. While the primary function was promotional, the images live on as a major documentation of this key period in history.

Who was Francis Wolff?

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of Francis Wolff (1907-1971) as both a photographer and key figure in the history of jazz. But Wolff’s story could have turned out very differently. A Jewish, jazz loving photographer in Berlin, he managed to escape Nazi-controlled Germany on the last boat bound for America in late 1939.

On his arrival in New York, he connected with his childhood friend Alfred Lion who had just established a jazz label – Blue Note Records. Wolff quickly became involved with the business and over his long career, he photographed the biggest names in jazz. His archive contains over 20,000 images captured over more than 3 decades and provides an invaluable record of the development of jazz. Thanks to the dedicated work of the late producer Michael Cuscuna, Wolff’s work lives and continues to inspire the visual aesthetic of Blue Note records.

How did he work?

The success of Wolff’s photographs for Blue Note is rooted in the trust and friendship he fostered with the musicians he captured.

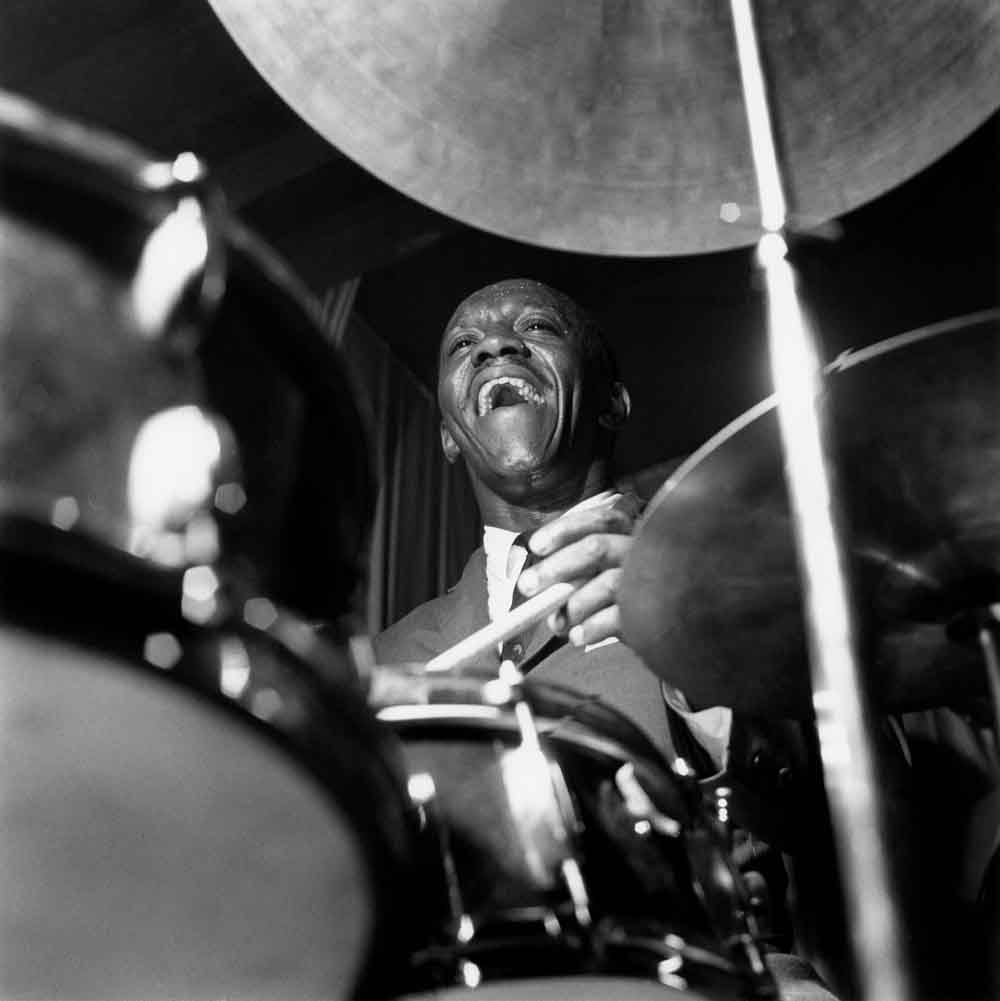

A key executive at Blue Note, Wolff was a familiar presence at rehearsals and recording sessions, which gave him opportunities to capture exceptional musicians deep in the zone of playing. His signature move to shoot close, from below, depicts his subjects as iconic and worthy of our admiration. It’s worth noting that many of these close up shots were possible because Blue Note took the unusual decision to pay musicians for rehearsal time. A snapping camera certainly wouldn’t have been as welcome had the tape been rolling.

How would you describe his style?

There are two camps to Wolff’s photography: energy and intimacy. His use of stark flash freezes the moment: fingers rap the piano, sweat builds, smoke from a cigarette rises, artists close their eyes and bite their lip as they feel the music. The images are unposed and alive.

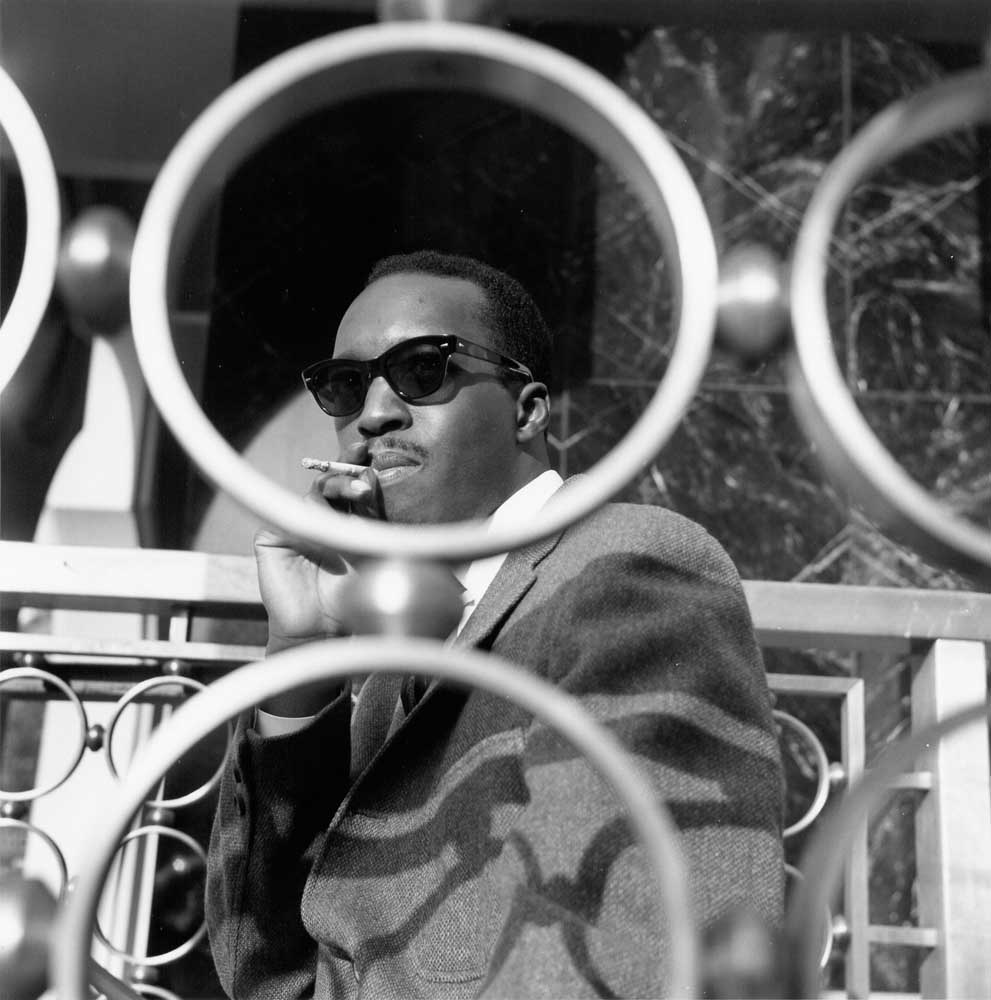

The latter are quiet, meditative moments from often spiritual musicians, deeply committed to their craft and with a calling to create music. Wolff provides a secret glimpse into the downtime of what would become iconic sessions.

The consistency of visual style throughout Wolff’s work is impressive, even as he later adopted colour by using the film Ektachrome, a slide or colour positive film known for capturing rich colours and contrast.

Wolff’s work could have easily been lost or overpowered during the album cover design process, but the partnership with designer Reid Miles saw Wolff’s stark and graphic style married perfectly as Miles explored the duotone covers, bold fonts and block shapes that are synonymous with Blue Note today.

Talk us through some of your favourite photographs?

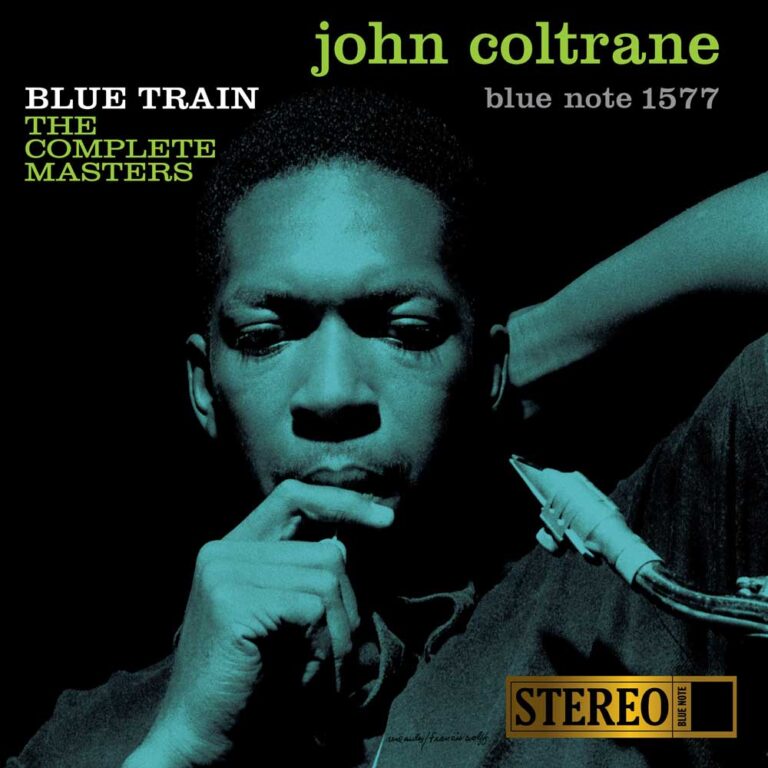

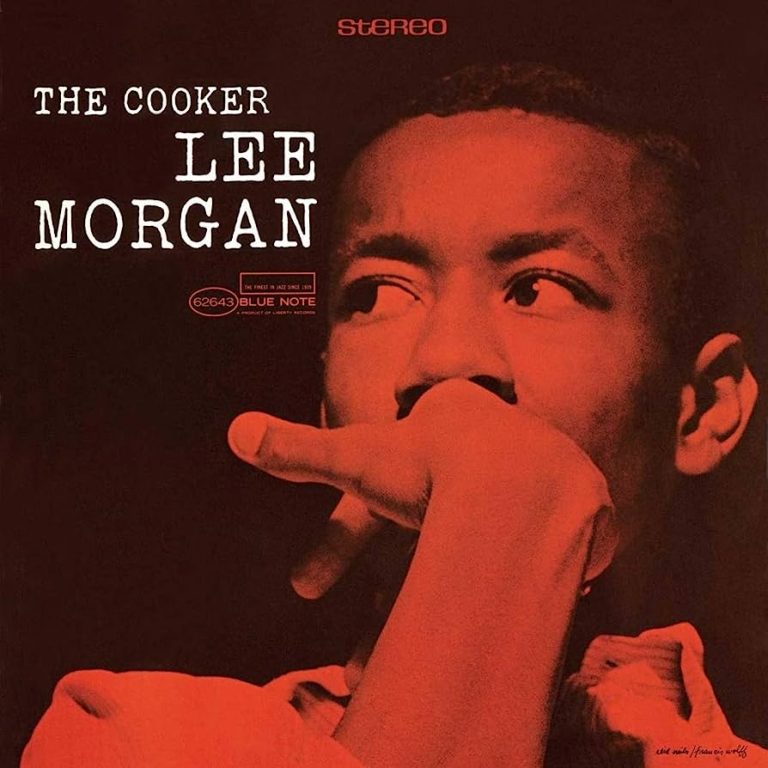

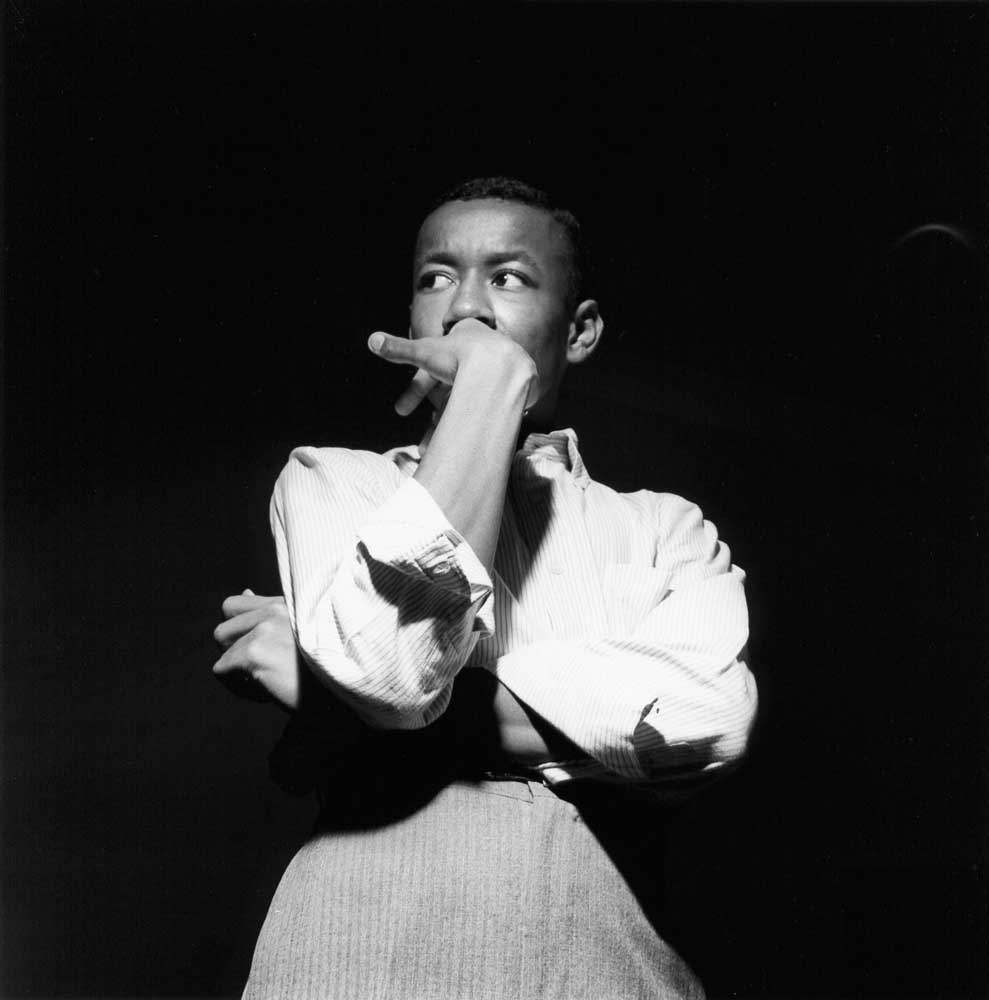

Lee Morgan – The Cooker (1958) & John Coltrane – Blue Train (1958)

On 15 September 1957, John Coltrane recorded Blue Train. Sideman Lee Morgan was photographed at the session and the photograph became the cover for Morgan’s own album “The Cooker”, recorded two weeks later.

They are both really similar shots. I don’t know if something was in the air that day but there’s a pensive vibe. The other images in the contact sheet are also very quiet, each shot of the 12 frames feels like the space between something happening. In another shot Kenny Drew is sitting on the ground also in thought. In the cover photos both artists have their hands to their face. They could almost be the same cover: one red, one blue.

I read that people thought John was holding a reed in the shot but actually it’s a lollipop.

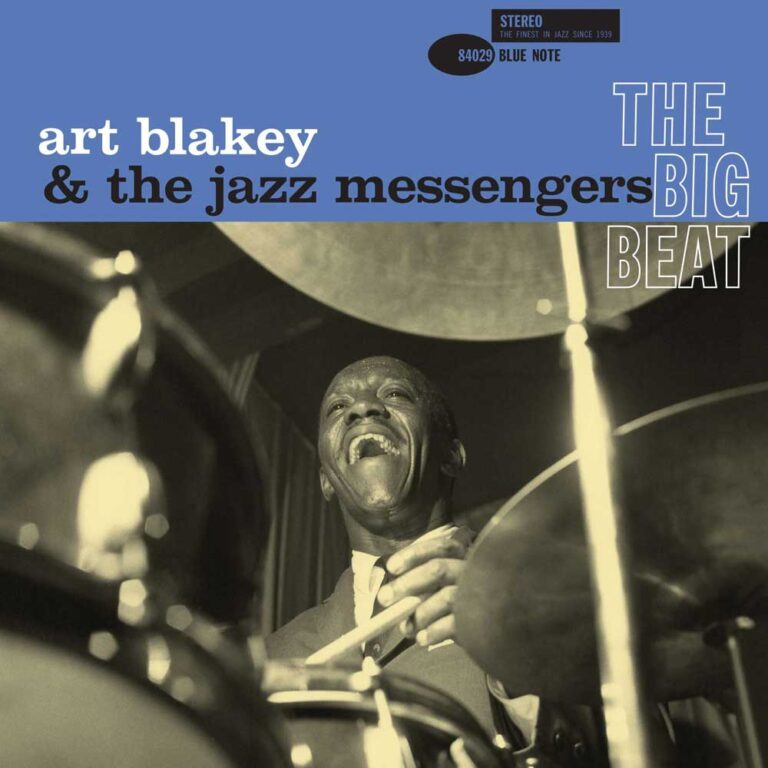

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers – The Big Beat (1960)

Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers were playing at Cork ‘N’ Bib in Rosalyn, Long Island while recording “Moanin’” in October 1958. Francis Wolff went out to shoot the band live and came up with this joyous shot that became the cover of Blakey’s “The Big Beat”. You can’t help but smile as you see the glint in his eyes.

Look at the image and think about where Wolff is actually placed while shooting it. He is right under there, almost inside the drum kit! Recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder was known for closely micing the musicians, and Wolff does the exact same thing with his photographs.

Ornette Coleman – At the Golden Circle Stockholm (1966)

In December 1965, Francis Wolff flew to Stockholm to capture the Ornette Coleman Trio at the Golden Circle which produced two volumes of classic live albums for Blue Note. Francis persuaded Colman, double bassist David Izenson and drummer Charles Moffett out in the freezing winter to Humlegården Park for a photo session. It was the 11th of 12 frames shot by Wolff that became the cover, and you can see from the contact sheet that it was snowing. It must have been uncomfortable for the trio who weren’t warmly dressed for a Scandinavian winter!

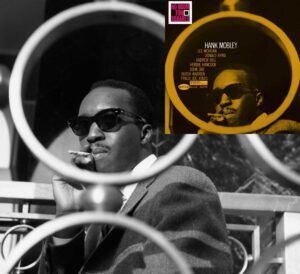

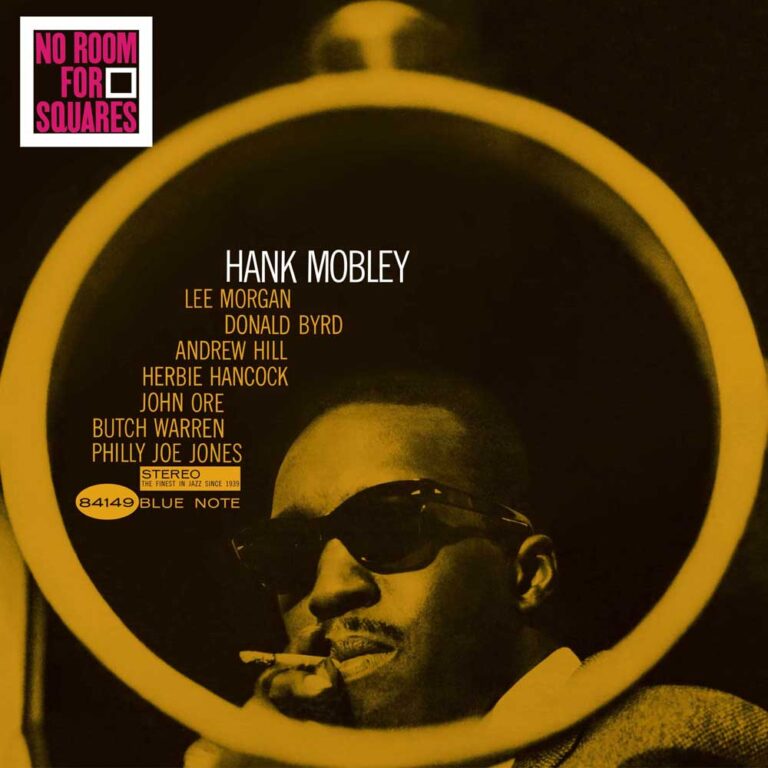

Hank Mobley – No Room for Squares (1964)

Francis Wolff was a man who obviously paid attention to his surroundings. In October 1963 he took saxophonist Hank Mobley onto the streets of New York City to shoot the cover image for “No Room For Squares.” His clever use of the circular railings at the subway station outside the Huntington Hartford building on the south end of Columbus Circle was a gift for his artistic partner, the graphic designer Reid Miles, who created an iconic cover. The circular motif was really on trend for the 1960s but is also a playful nod to the album title.

Verity Roberts is the Picture Editor for Everything Jazz. She manages visual content for brands including Universal Music, BBC and Magnum Photos.

All photographs: Francis Wolff / Blue Note Records.