Miles Davis’s “Bitches Brew” and Herbie Hancock’s “Head Hunters” – two seismic albums in the history of jazz in the 20th century, and neither would have been quite the same without the presence of the individual, distinctive multi-reedist Bennie Maupin. On bass clarinet, possibly only the tragically short-lived Eric Dolphy rivals Maupin in bringing the instrument to the fore in jazz. Maupin’s bass clarinet is one of the vital ingredients of the brew on Davis’s pivotal 1969 album, helping paint this new tapestry of sound that sent shock waves through the jazz scene. On Hancock’s groundbreaking 1973 “Head Hunters”, Maupin’s bass clarinet is heard to beautiful effect on the hypnotic closing track “Vein Melter” – while elsewhere on the album his arsenal of winds encompasses tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone, saxello and alto flute.

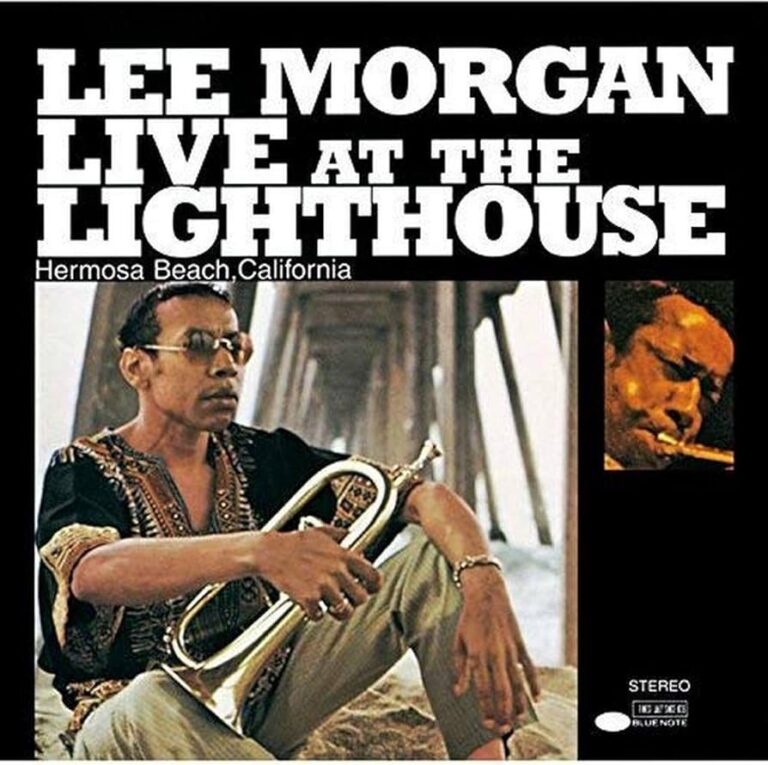

Recording only sporadically as a leader over the decades, Maupin’s main legacy is perhaps as a sideman of the highest calibre. Anyone wanting to hear Maupin in blistering form on tenor saxophone should head straight to Lee Morgan’s incredible 1970 “Live at the Lighthouse” on Blue Note – a significant document of high energy post-bop acoustic jazz reaching its artistic, if not commercial, zenith at a time when the world was turning its back on the genre.

As sideman, Maupin’s most significant association was with Herbie Hancock, with whom he was a crucial element of Hancock’s music right through the 1970s – including co-composing two of the key tracks of this era, “Chameleon” and “Butterfly”.

Maupin first joined Hancock as part of his groundbreaking Mwandishi group at the very start of the decade. He was the only member to be kept on when the group disbanded and Hancock made the dramatic stylistic shift from the searching sonic experimentation of the Mwandishi group to the earthy funk of “Head Hunters”. To both contexts, Maupin brought a breadth and beauty of texture with his multiple woodwinds, along with an advanced harmonic language and individuality of tone that places him in the lineage of tenor saxophone peers such as Wayne Shorter and Joe Henderson.

Maupin’s debut as leader was in 1974, with the singular, beautiful, predominantly acoustic “The Jewel In The Lotus” – his one album for the iconic ECM label. Recorded with a line-up primarily of fellow band-members of the Mwandishi group, it is also Herbie Hancock’s one and only appearance on ECM.

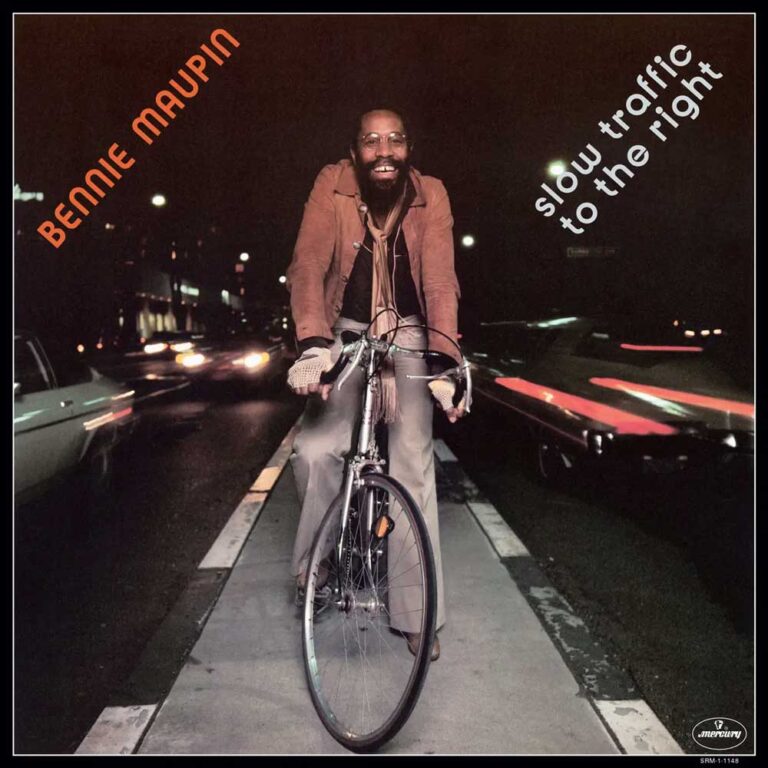

Maupin’s second album, “Slow Traffic To The Right” from 1977, is infused with the jazz funk of the Head Hunters. Although not featuring Herbie Hancock, the music is closely aligned with Hancock’s musical developments at this time, in particular the album “Secrets”, which was recorded at around the same time.

A range of Hancock sidemen from his different 1970s bands are present – bassist Paul Jackson, drummer James Levi, guitarist Blackbyrd McKnight, trumpeter Eddie Henderson – and the album is produced by synthesiser pioneer, and former Mwandishi band member, Patrick Gleason, who was the man who first introduced Herbie Hancock to the possibilities of synthesisers. The keyboard role is taken by the wonderful Patrice Rushen.

Opening track “It Remains To Be Seen”, composed by Maupin, is a highlight of the album. Jackson (a unique player who was crucial to the sound of much of Hancock’s 1970s music) and Levi provide the grooving rhythmic foundation, along with the distinctively funky rhythm guitarist Blackbyrd McKnight (who appeared on Hancock’s “Flood” and “Man-Child” albums, and worked with Maupin, sans Hancock, in offshoot band The Headhunters), giving a solid grounding for Maupin’s distinctive soprano to soar. Rushen also contributes a standout piano solo. In some ways the track feels like a lost track from “Secrets”, and although the composition never appeared on any official Herbie Hancock release, it does appear on a Hancock bootleg live recording from this period (with star bassist Jaco Pastorius subbing for Paul Jackson).

Maupin’s playing and compositions here show just how significant a part of Hancock’s 1970s music he was, while also shining as his own man. The short, pared-down bass clarinet and piano duet “Lament” showcases his individuality on the instrument. Elsewhere, two Maupin compositions, “Water Torture” and “Quasar”, are given radically different treatments to when they both appeared on Hancock’s Mwandishi group album “Crossings” (1972).

Now aged 84, very sadly Bennie Maupin’s home burned down in the recent Los Angeles fires, losing his possessions, including instruments and music, but thankfully not his life. Having had the privilege of witnessing Maupin perform live just last year with Herbie Hancock – for a one-off celebration of 50 years since the “Head Hunters” album, at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles – I very much hope that this unique musician will recover from this and continue to gift the world with his music. For fans of 1970s jazz funk, “Slow Traffic To The Right” is a hidden gem. Maupin has been a crucial contributor to other artists’ music, but on the rare occasions when he has recorded as leader it is always worth taking notice.

Jon Opstad is a London-based composer working across film & television, contemporary dance, concert music and album projects. His scores include the Netflix hits Bodies and Black Mirror, and Elisabeth Moss thriller The Veil, co-composed with Max Richter. An avid record collector, he has a particular affinity for the music of ECM.

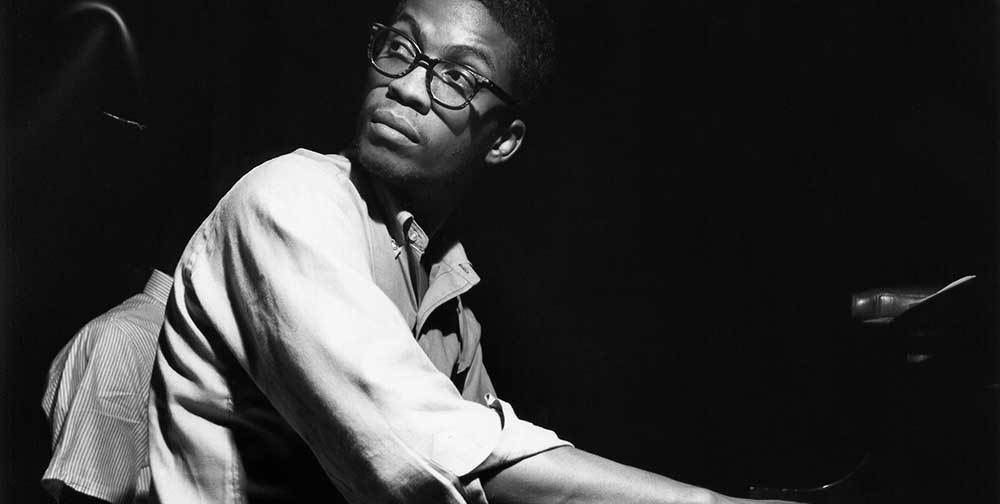

Header image: Benny Maupin performing in Berkeley, California. Circa 1978. Photo: Tom Copi/Michael Ochs Archives.