“After The Last Sky”, the title of Anouar Brahem’s most recent album, is a reference to a poem by Palestinian writer Mahmoud Darwish. It’s not the first time that Darwish gets mentioned in Brahem’s work over his four-decade career. 2009’s “The Astounding Eyes of Rita”, a mystical record drawing from Scandinavian jazz and Arab classical music, was dedicated to the late poet as well.

In fact, Brahem never shied away from political statements. In 2006, the Tunisian musician and composer directed and co-produced a documentary film set in Lebanon, “Mots d’après la Guerre”, focusing on the war between Israel and Hezbollah. During the early days of the Arab Spring, Brahem wrote dramatic pieces of orchestral music that would turn into the base layer of his 2014 double album “Souvenance” – a personal response to the upheaval in his homeland.

Born in 1957 in Tunis, Anouar Brahem started playing oud at the age of 10, attending the National Conservatory of Music. Talented and gifted, he was mentored by Ali Sriti, a venerable master of Arab classical music. His hometown had a huge influence on the young musician – in the Tunisian capital, Arab-Muslim roots have been mixing with cultural influences from Africa and the Mediterranean for centuries.

Soon the young oudist discovered his true vocation – he didn’t aim to accompany vocalists, perform at weddings or in orchestras, but wanted to develop his very own, distinctive compositions that fused all of his various influences, effectively turning the oud into a sophisticated solo concert instrument.

Spending the 1980s between Tunis and Paris, Brahem worked mainly on ballet, film and theatre music. Already then one of the most influential Arab musicians of his generation, he experimented a lot in this time and explored his new surroundings, collaborating with select French jazz musicians.

In 1990 he met ECM producer Manfred Eicher – their mutual admiration turned into a decade-long collaboration, which is still ongoing. “After The Last Sky” was recorded in May 2024 in Lugano and produced by Eicher. In the 34 years between, Brahem has released 11 full-length records on the German label, all critically acclaimed and winning him a loyal fan base around the globe.

The ECM connection opened certain doors to new personnel: On his next albums, Brahem would play with Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek and Pakistani tabla master Shaukat Hussain (“Madar”, 1994), or British improvised music innovators John Surman and Dave Holland (“Thimar”, 1998). The contemplative, ambient-jazz-leaning “Thimar” became one of his biggest commercial successes so far, winning several awards and garnering general acclaim.

“Le Pas du Chat Noir”, a trio recording from 2002 with pianist François Couturier and accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier, fused Brahem’s Arab and Mediterranean roots with French impressionist composition. The writer Adam Shatz – who also penned the liner notes for “After The Last Sky” – wrote in the New York Times that this music “evokes a kind of 21st century Andalusia, where Arab and European sensibilities will have fused together so intimately that no frontier can any longer exist between them. All that might seem Utopian, but the beauty of this project is indisputable.”

“Blue Maqams”, Brahem’s 2017 album dedicated to jazz improvisation within the modes of Arab classical music, turned into one of his most beloved records as well. The personnel on that record included Dave Holland, Django Bates on piano and Jack DeJohnette on drums, who’d once been Tony Williams’ successor in Miles Davis’ band.

The most recent entry in Brahem’s rich discography, “After The Last Sky”, is a deeply meditative quartet album, again with Dave Holland and Django Bates in the line-up, but also including cellist Anja Lechner, who brilliantly infuses Brahem’s poetic chamber music with melancholic, post-romantic string melodies.

Brahem wrote the material for this album witnessing the ongoing horrors of the Gaza war. He’d occupied himself with the Palestinian question since his 1980s days among students, intellectuals and artists in Paris and Tunis. Still, in his eloquent liner note essay, the aforementioned writer and scholar Adam Shatz insists that “After The Last Sky” shouldn’t be framed as protest music, as that would severely weaken its effect.

Anouar Brahem knows that music and art have the power to transcend matters of politics and history. In Shatz’ essay, he is quoted saying that “instrumental music is by nature an abstract language that does not convey specific ideas. It is aimed more at emotions, sensations, and how it’s perceived varies from one person to another. (…) I invite listeners to project their own emotions, memories or imaginations, without trying to ‘direct’ them.”

In other words: “After The Last Sky” bears no message, because it doesn’t need to. Its mere existence is a reflection of its profound humanity, creating a de-facto antithesis to the darkness and despair around us, possibly lending us a slight glimmer of hope, empathy and compassion – which might be more than any outspoken protest music could achieve.

Stephan Kunze is a writer, book author and a commissioning editor for Everything Jazz. He writes the zensounds newsletter on experimental music and culture.

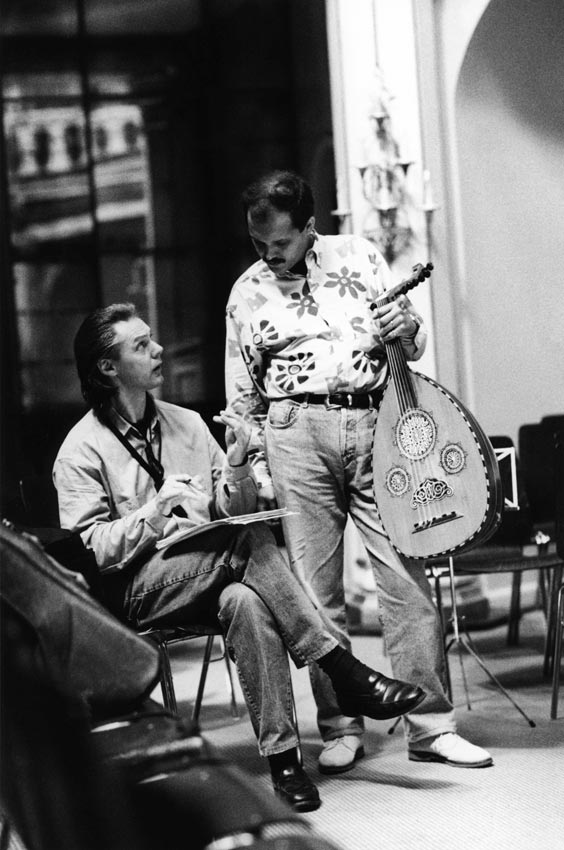

Header image: Anouar Brahem. Photo: Sam Harfouche.