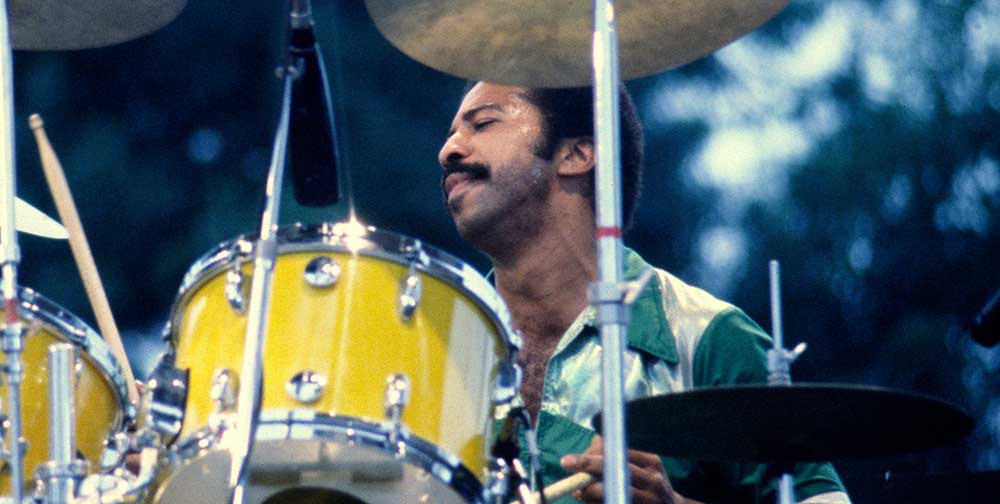

Tony Williams will always be best remembered for his world-shaking tenure as drummer for Miles Davis, starting in 1963 when he was just 17 years old. Through the years of Miles’s Second Great Quintet, from 1964 to 1968, alongside the youthful cohort of tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock and bassist Ron Carter, Williams helped to redefine the role of the drummer – and time itself – moving away from the shackles of strict metre toward a much more fluid approach that was every bit as radical as the contemporaneous free jazz explosion.

But, during this period, he was also a key player on several epochal Blue Note dates that were at the vanguard of progressive post-bop, contributing both impetuous urgency and timbral grace to Eric Dolphy’s “Out To Lunch!” (1964) and Andrew Hill’s “Point Of Departure” (1965). At the same time, his first two albums as a leader – both recorded for Blue Note – revealed a serious conceptualist committed to stretching beyond the tradition. “Life Time” (recorded in 1964, released the following year), and “Spring” (recorded 1965, released 1966) both drew on the talents of his colleagues from Miles’s Quintet, plus outliers including bassist Gary Peacock who was then fresh from breaking down walls with free jazz pioneer Albert Ayler’s trio.

It would be another two decades before Williams recorded for Blue Note again. After spending the late 1960s and 1970s spearheading the jazz-rock fusion movement – with Tony Williams Lifetime and Trio of Doom – in the mid-1980s, Williams caught hold of the back-to-bop zeitgeist of the so-called Young Lions and made a return to acoustic jazz. In truth, it was something he had never really left behind: even while pushing the fusion agenda, he’d still found time to perform with erstwhile Miles Quintet alumni, Shorter, Carter and Hancock in the V.S.O.P band, with Blue Note stalwart Freddie Hubbard taking over trumpet duties from an out-of-action Miles.

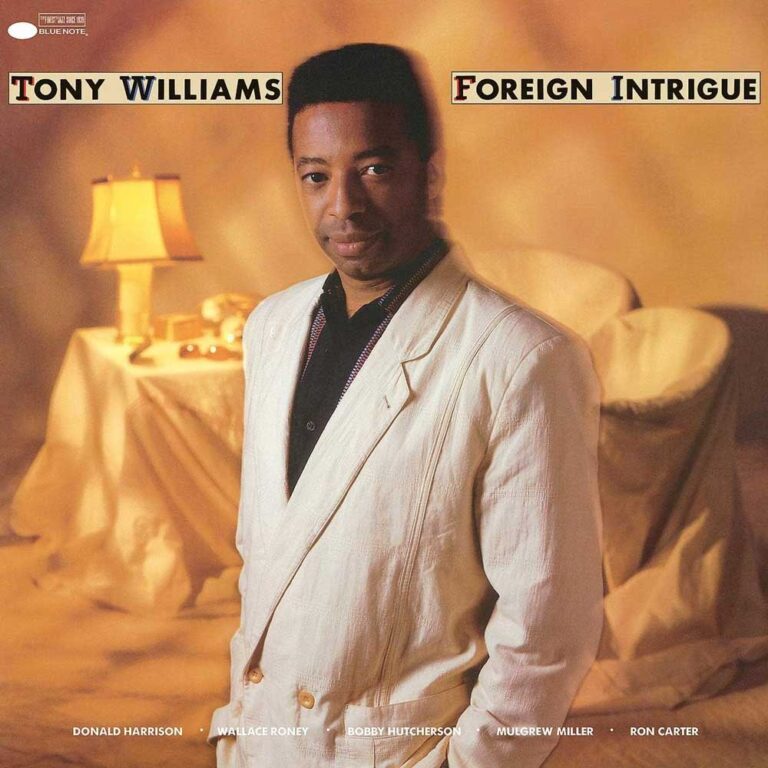

Williams’ overdue return to Blue Note came in 1985 with his critically lauded album “Foreign Intrigue“, for which he assembled a multi-generational band featuring old buddies Carter and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, alongside a handful of Young Lions – trumpeter Wallace Roney, alto saxophonist Donald Harrison and pianist Mulgrew Miller. Williams’ seven original compositions proved that, for all his electric explorations, he’d never lost touch with the deepest source of jazz tradition.

It was a direction Williams enthusiastically pursued the following year with the release of “Civilisation”, the debut album by his new hard bop quintet which retained Miller and Roney, adding another up-and-coming player, bassist Charnett Moffett, and the more experienced saxophonist Bill Pierce. With its eight tracks again all composed by Williams, it signalled an even deeper dive into acoustic jazz than its predecessor. Where “Foreign Intrigue” had included electronic augmentations, on “Civilisation” the electronics are limited to subtle additional drum machine rhythms, giving the album a more evergreen feel. At the same time, Williams seems to relish bringing the power and grand scale of his fusion experiments back into a hard-swinging context with crashing snare and voluminous toms summoning a great muscular urgency that never obscures his deep sense of swing.

Williams’ exuberance also pushes his sidemen to sink their teeth into the material with gusto. Uptempo hard-bop jams like “Warrior” and “Mutants On The Beach” roil and swell, eliciting powerful solo statements from all. “Soweto Nights” is a deeply satisfying modal groove hung on a loping bassline, which – at about the half-way mark – morphs briefly into a double-time sprint that revisits the daring temporal innovations Williams had pioneered with Miles twenty years earlier.

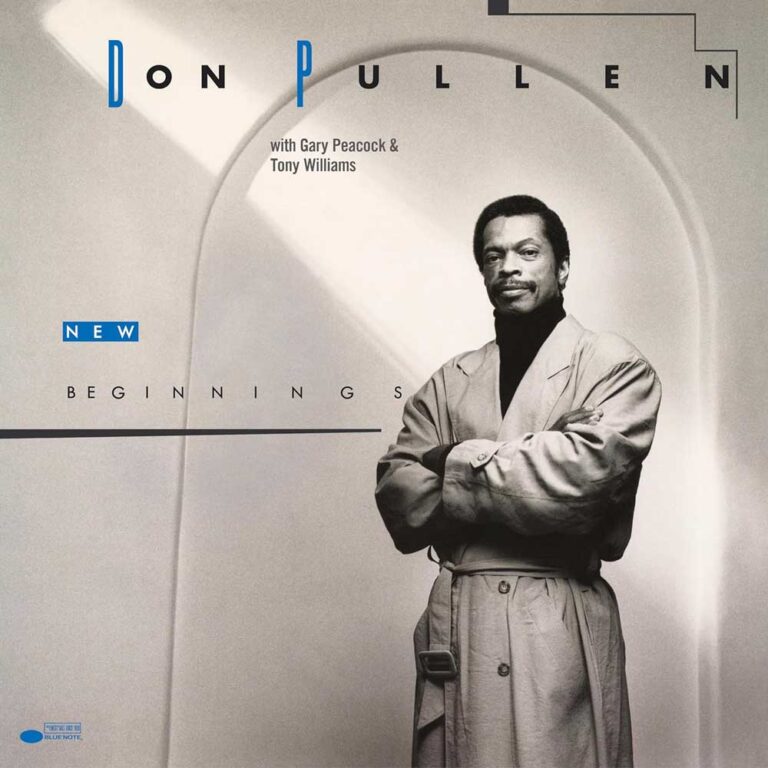

While the dense and boisterous arrangements on “Civilization” sometimes feel like Williams is fighting for air, he has plenty more room to breathe on another late-1980s Blue Note date led by pianist Don Pullen. Initially coming to prominence playing with Charles Mingus in the 1970s, Pullen had become part of the Blue Note stable with two albums recorded with a quartet co-led with saxophonist/flautist George Adams – “Breakthrough” (1986) and “Song Everlasting” (1987). In 1988, he began a fresh phase with the aptly named “New Beginnings”, a date for his new trio featuring Williams, reunited with the brilliant bassist Gary Peacock.

Here, again, Williams is a big presence, pushing the tunes ahead with a punchy attack, but he also has enough sensitivity to pull back and let Pullen lead. Pullen is a mischievous and quixotic presence throughout, gleefully upending the expectations set by his deceptively conventional compositions. “Jana’s Delight” is a carefree groove with just a hint of Vince Guaraldi’s sunshiney vamps; “Once Upon a Time” is a sprightly waltz with Williams straining at the leash; “Warriors” is an urgent Latin prance.

Throughout all of these, Pullen derails proceedings with sudden spurts, scurries and karate chops, injecting rogue doses of avant-garde energy, brewing an unhinged feeling of controlled chaos, as though the tunes are only just managing to cling on to form. It all comes together with thrilling immediacy on “Reap the Whirlwind,” which leans more heavily into the avant-garde, Pullen crashing around manically on the keyboard, Peacock galloping off on super-charged lines and Williams rattling and thundering like an imperious god of percussion.

As these two overlooked gems from the 1980s Blue Note catalogue make clear, if ever there was a musician who had a knack for being in the most exciting place at the right time, it was Tony Williams.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a biography of saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

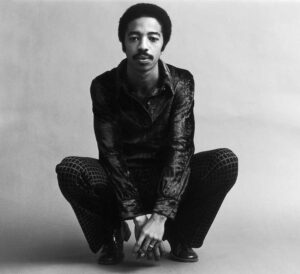

Header image: Tony Williams. 23rd September 1969. Photo: Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.