Back in 1958, few had heard the likes: the scatting. The audacious reworkings. The husky tones that turned on a dime, changing tempo here, altering dynamics there, recalling a trumpet, a trombone, the golden slaloms of a tenor sax. There was the way she felt, like really felt, every goddamn word she sang.

“What did I do to you?” she demanded, magnificently unhinged, on Walter Donaldson’s “You’re Driving Me Crazy”, the opening track on “Out There”, her bebop-tastic debut.

Her name was Betty Carter, and she was 28 years old. ‘Betty Be-Bop’ she’d been nicknamed by Grace Hampton, wife of vibraphonist and big bandleader Lionel, in whose group she’d got her break from 1948–50. Her bandmates included bassist Charlie Mingus, rising star guitarist Wes Montgomery and several players with links to Dizzy Gillespie. It was Dizzy who’d heard the Detroit-raised Carter, the daughter of a church musical director, at an amateur night and waxed lyrical about her prowess.

Resolutely independent, preternaturally confident – as a young teen she’d sneak out to audition for amateur shows, flashing her forged birth certificate to get in. Carter never compromised, either on the beauty of her medium or the singularity of her style.

She set out her stall on her self-penned “I Can’t Help It”, the only original among “Out There”‘s 12 tracks: “Have you considered what it does to your soul? You sell it when you play someone else’s role,” she sang, underscoring her authenticity while pushing the edges of melody and harmony.

Charlie Parker, another architect of the bebop style, also rated the teenage Carter. She’d worked with his band, with its burgeoning luminaries Miles Davis, Tommy Potter and Max Roach, unfazed and fabulously free-bopping. Maybe unsurprisingly, whenever Hamp asked her to swing, she would so begrudgingly; he’d gone on to fire ‘The Kid’ – his nickname for Carter – several times over. It is largely thanks to Hampton that Carter is feted as one of the last big band jazz-era singers. But by 1951 she was in New York City, singing at the Apollo, owning the spotlight.

And in the same way that planets orbit the sun, so did a who’s who of stellar sidemen front up to feature on “Out There”: Ray Copeland is there on trumpet. Melba Liston, the jazz trombonist, arranger and Randy Weston collaborator (Weston’s song “Babe’s Blues”, co-written with Jon Hendricks, is here). The now mythical Gigi Gryce is here, too, leading the ensemble on alto sax, taking a break from leading the Jazz Lab Quintet (1955–58) with Donald Byrd, helping to maintain the dynamism through tunes including Jimmy Van Heusen’s “But Beautiful” and Rogers & Hammerstein’s “Something Wonderful” – each song given the Carter twist.

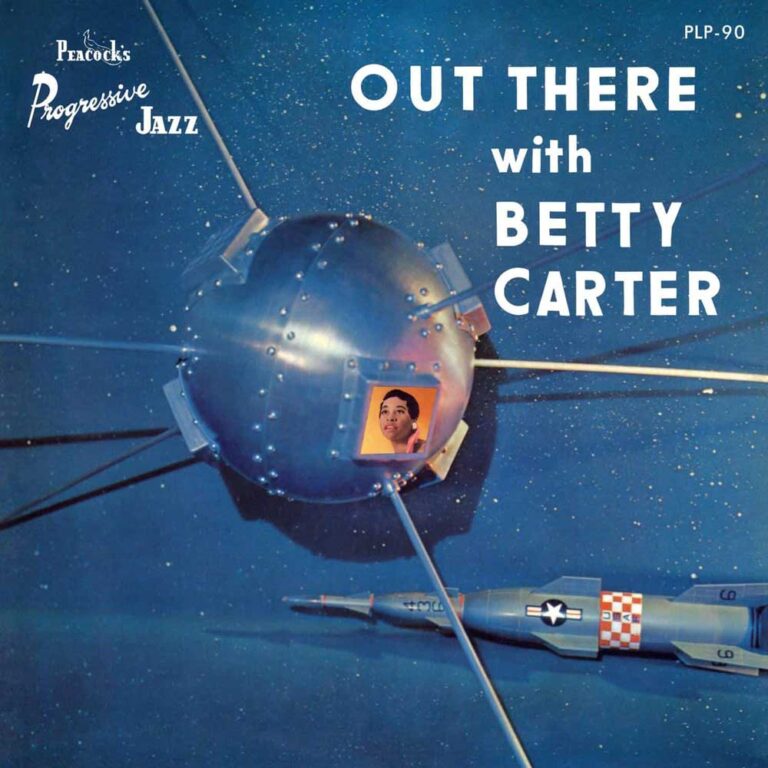

To listen to “Out There” is to marvel at the way a girl from Detroit, a mecca for Black American music, harnessed her remarkable tenacity and talent to be-bop her way into the public domain and beyond. That the album’s cover depicts a sputnik with Carter’s face peering out into a starry galaxy, three years before the first moon landing, is further proof that here was a jazz singer going where few dared to go.

In the 1960s, Carter would record with Ray Charles, tour with Sonny Rollins and create on her own Bet-Car record label. Her epic 1980 double LP “An Audience With Betty Carter” would rank as one of the best jazz albums of all time. But “Out There” is where it all began, the blast-off into the jazz stratosphere.

Jane Cornwell is an Australian-born, London-based writer on arts, travel and music for publications and platforms in the UK and Australia, including Songlines and Jazzwise. She’s the former jazz critic of the London Evening Standard.

Header image: Betty Carter. Photo: Frans Schellekens/Redferns.