When “A Love Supreme” was recorded on December 9, 1964, it was the midpoint of a decade that was about to catch fire. Global shifts in politics, culture, and spirituality — in society in general — were right around the corner. In its sound and spirit, John Coltrane’s most enduringly popular album was the right sound and the right idea at the right time.

For the members of Coltrane’s classic quartet — pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, drummer Elvin Jones — and recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder in whose studio A Love Supreme was recorded, it was another day at work, another session in Englewood cliffs, New Jersey. But for Coltrane, it represented something more personally relevant and profound: a chance to present a musical statement that carried a deeply held spiritual vision of universality, in which “all paths lead to God,” and to share this philosophy with a growing audience.

JOHN COLTRANE A Love Supreme

Available to purchase from our US store.“I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music,” Coltrane would write on A Love Supreme, describing his plea to a universal, divine force. “I feel this has been granted through his grace.”

By all measures, Coltrane’s prayer was granted, and is still being fulfilled. The world took to “A Love Supreme” with widespread applause upon its release. It proved a bestseller, earning a gold record distinction for 50,000 units sold, and two Grammy award nods. It helped raise Coltrane’s popularity to its highest point during his lifetime. Down Beat saw the album as a marker to what it called “the year of Coltrane”, placing the saxophonist on its cover the month it published its annual readers’ poll, heralding his top position in three categories and his induction into the magazine’s Hall of Fame.

The general embrace of “A Love Supreme” was as immediate as it was unlikely. When consumers first placed the needle on that record, most were unprepared for the music. It was unusual in structure, sound, and especially in its avowed purpose: on the album’s inside cover, Coltrane had provided a poem and a letter to the listener declaring the album “a humble offering” to god. If this was a first-time experience with Coltrane’s music, it required patience and focus. Even longtime fans and musicians were challenged.

To many whose ears were attuned to black American music, “A Love Supreme” resonated like church and tracked with the cadence and intensity of a gospel service: a warm call to worship (“acknowledgement”), that balanced a familiar hymn-like chant with Sunday-morning energy; congregational orders of business followed with moments of group and individual statement interspersed with preacher-like messages and finally a sermon (“resolution”, “pursuance’) closing with a hushed, personal testimonial (“psalm) and a sober benediction to all. On closer listen, it sounded more ecumenical: blues flavours abounded, as did Latin rhythmic accents and hints of eastern folk sources.

One did not need to pull the vinyl from the sleeve to know that this was music of deep, spiritual intent. Coltrane’s words on the cover spoke of God and music and earthly struggles and spiritual salvation. It was the first and last time he would pen his own album notes. And his voice chanting the album’s title on the opening track — the first time he added his voice to a recording — all deemed “A Love Supreme” a deep and disarmingly personal testament.

Today, in music and message, “A Love Supreme” continues to cast a shadow of influence wide, across lines of generation and genre. Hip-hop producers and emcees quote from it. Rolling stone and other pop/rock list-keepers consistently place it among the top 50 (or 25 or 10) albums of all time — one of the very few jazz recordings to maintain that ranking. In the jazz world its stature is unquestioned, serving as a touchstone by which any project weaving together musical and spiritual intention is measured.

“A Love Supreme” stands as Coltrane’s universal testament, his non-denominational sermon of devotion, his namaste. Exactly sixty years since its arrival, voices that speak of divine connection and supreme love are once again having trouble being heard. The lines that would divide one people from another seem unbending and are running deep. In a world at odds with itself, Coltrane’s magnum opus remains more relevant than ever.

Read On…John Coltrane’s Criminally Underrated Record

Ashley Kahn is a Grammy-winning American music historian, author, professor and producer. He teaches at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute for Recorded Music, co-wrote Carlos Santana’s award-winning autobiography The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light (Little, Brown, 2014), and is a producer of Carlos (2023), the documentary on Carlos Santana (Imagine Documentaries/Sony Pictures Classics.

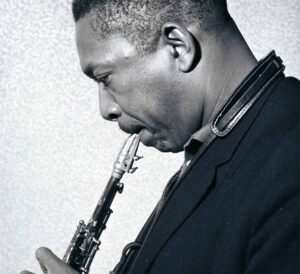

Header image: John Coltrane. Photo: Bill Wagg/Redferns.