While still in his early 20s, Max Roach was an early pioneer of bebop and played on Charlie Parker’s epochal Savoy sessions in November 1945, which announced the arrival of this daring new sound to the world. Together with Kenny Clarke, Roach devised a whole new approach to drumming, freeing it from its slavish timekeeping role and creating space for subtlety and surprise – a revolutionary breakthrough that set the template for modern jazz drums. As well as Parker, Roach accompanied a pantheon of bebop originators including Dizzy Gillespie, and pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell.

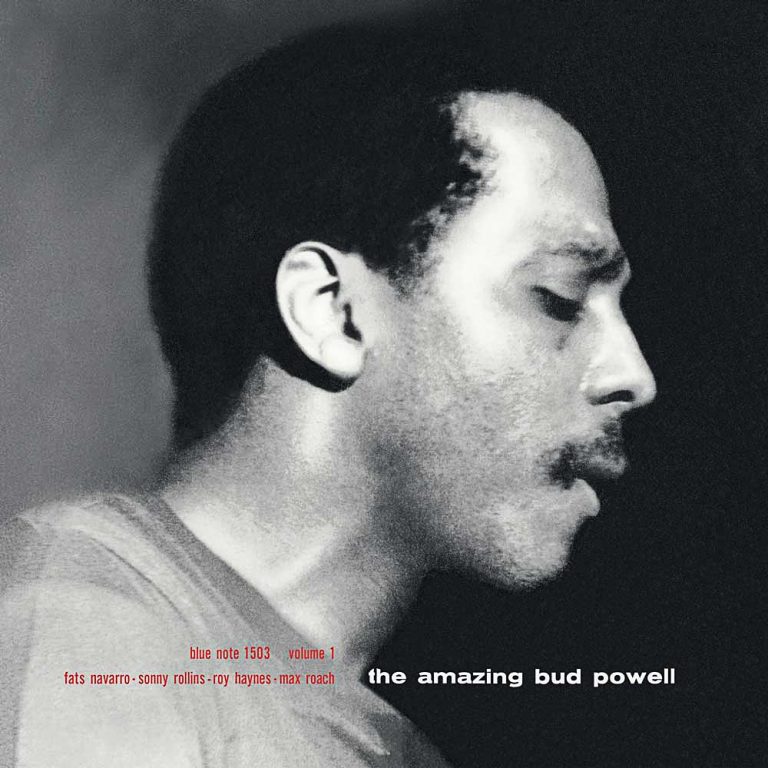

Along with bassist Curly Russell, he was part of the Bud Powell Trio that recorded a 1951 session released on Blue Note as one half of “The Amazing Bud Powell Vol. 1” in 1952. Roach’s quicksilver imagination illuminates this landmark recording – from his fiendishly syncopated ride cymbal and toms on the jaunty ‘Un Poco Loco’ to his crisply snapping brushes on ‘A Night In Tunisia.’

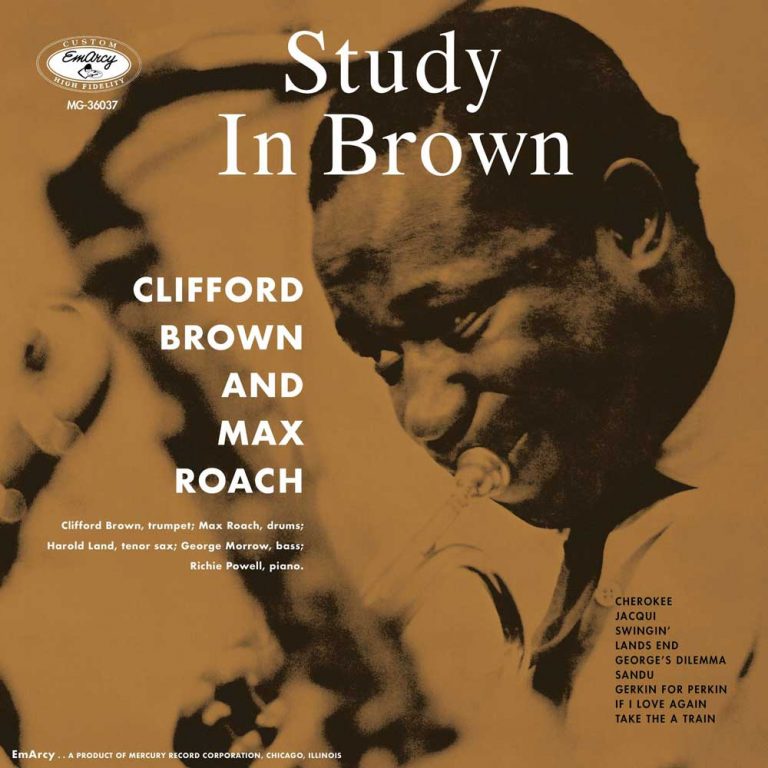

After the bright burst of bebop in the mid-1940s, Roach played a key role in the next major stylistic leap of the 1950s, as a driving force behind hard bop. In 1954, he and trumpeter Clifford Brown formed a world-shaking quintet also featuring tenor saxophonist Harold Land, bassist George Morrow and pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud).

This quintet was widely recognised as one of the leading hard bop bands of the day alongside Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers – and their 1955 album, “Study In Brown” shows exactly why. It’s a hard-hitting yet sophisticated mix of deep blues and heavy swing, with Roach demonstrating an almost telepathic ability to instantly add dramatic commentary to Brown’s ebullient flourishes. When Land left the quintet in 1955, he was replaced by Sonny Rollins, beginning a fruitful working relationship between Roach and the young rising tenor star.

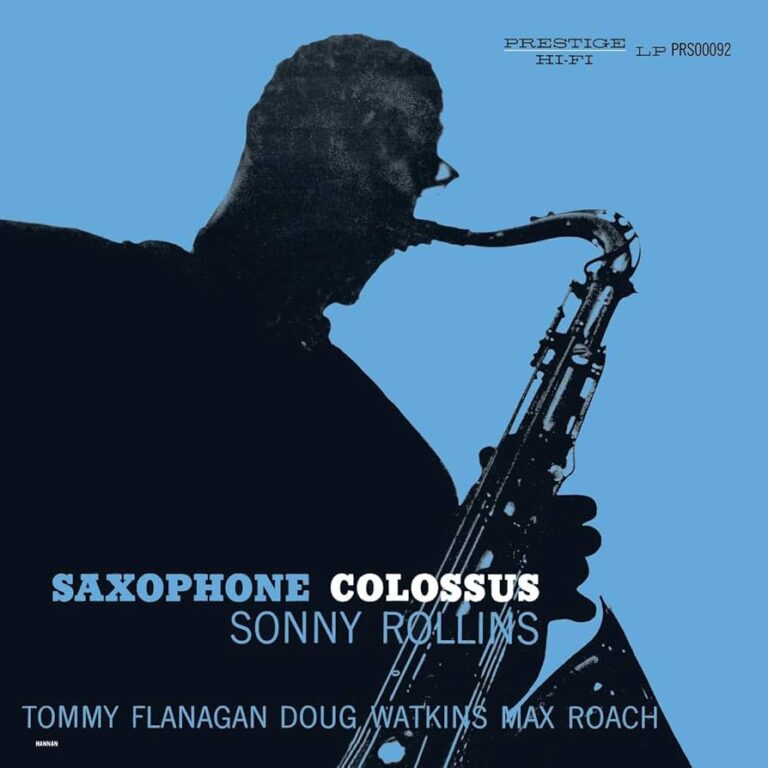

Roach is the backbone of Rollins’ breakthrough album as a leader, “Saxophone Colossus”, recorded 1956 and released the following year. Its opening cut, the lilting, calypso-inspired ‘St. Thomas,’ features a Roach drum solo that showcases just how much he’d been able to open up the melodic and expressive possibilities of the drum kit while, on ‘Strode Rode,’ he lets rip with a thrilling up-tempo velocity.

The album was recorded just four days before the fatal car accident that tragically killed Clifford Brown and Richie Powell, effectively cutting short the promise of the Brown/Roach Quintet – but Roach continued to record with Rollins, contributing to more of the saxophonist’s essential hard-bop dates, including the classic 1958 tribute to the Civil Rights Movement and cry for racial emancipation, “Freedom Suite”. On the 19-minute title track, Roach reveals his mastery of the drums as a story-telling instrument. Was any other drummer ever able to wring so much emotion from a simple hi-hat?

As the 1960s dawned, Roach’s own albums as a leader also began to focus more and more on the ongoing struggles of the Civil Rights Movement. 1960’s “We Insist!” was a strident suite of originals highlighting racial injustices in both the US and Africa, featuring the striking voice of vocalist Abbey Lincoln (who went on to marry Roach).

Released the following year, “Percussion Bitter Sweet” continues the political imperative. Opening track ‘Garvey’s Ghost’ (as featured on the Impulse! records compilation “Music, Message and the Moment”) is a powerful tribute to Black nationalist and Pan-African advocate, Marcus Garvey, incorporating Lincoln’s haunted, wordless vocals and a thick barrage of Afro-Cuban percussion with Carlos “Patato” Valdés on congas and Eugenio “Totico” Arangho on cowbell.

Here, Roach’s fascination with the rhythms of the African diaspora comes to the fore. As early as the late-1940s he’d travelled to Haiti to study with traditional drum master Ti Roro, and a firm belief in the spiritual properties of the drum enlivened all his subsequent work.

In the 1970s, Roach’s faith in the transporting power of rhythm led him to form the radical percussion orchestra, M’Boom, which called on the talents of heavyweight drummers including Joe Chambers and Roy Brooks. He also delved into free improvisation, performing duets with the likes of Cecil Taylor and Anthony Braxton. In the 80s and 90s, Roach enjoyed a well-earned reputation as a vital architect and elder statesman of jazz, until health issues forced him to drop out of the spotlight in the early 2000s.

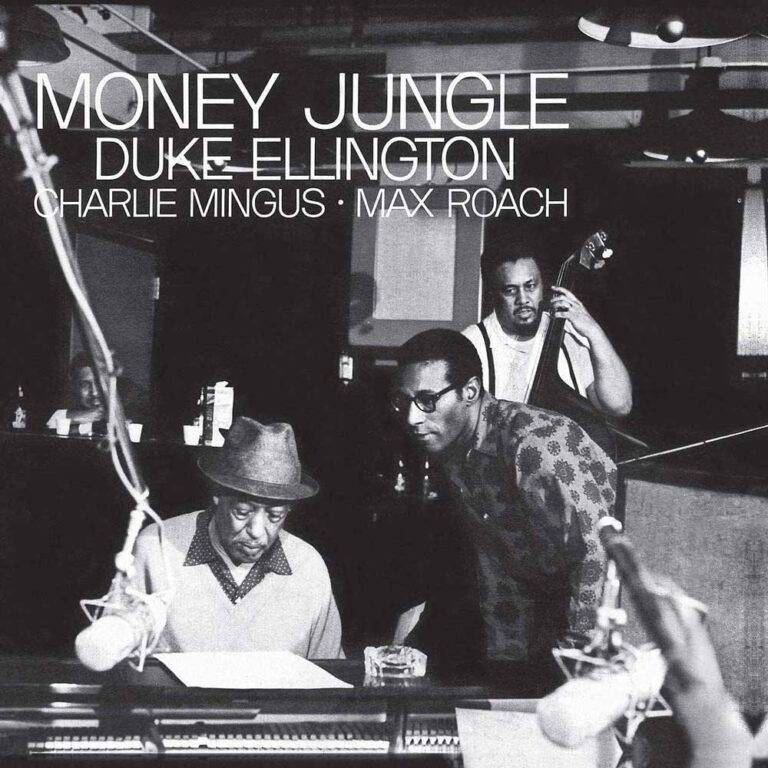

He finally died of complications related to Alzheimer’s in 2007 at the age of 83. Max Roach left behind a truly monumental discography of essential jazz classics – but perhaps one of his greatest legacies remains the 1962 studio date recorded with Duke Ellington on piano and Charles Mingus on bass, released as “Money Jungle”.

Bursting with wit and invention, this intergenerational gathering of giants seems to penetrate to the very essence of jazz and is generally held to be one of the most important and creatively rewarding trio albums ever recorded.

Read on…Beyond the Backline – 5 Band Leading Percussionists

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a biography of saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Max Roach. Photo: David Redfern/Redferns via Getty.