It’s not every day you sit down for a plate of rice and peas with a genuine living legend of jazz. In July 2015, I was in New York City, attending the 20th anniversary edition of the Vision Festival – an annual avant-garde showcase of free-jazz, poetry and dance. That year, the festival was held in Judson Memorial Church, a grand 19th century edifice adjacent to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. While the gigs took place in the church’s huge hall, downstairs was an informal space with stalls selling T-shirts and CDs, and delicious Jamaican food on paper plates. Here, audience members and musicians rubbed shoulders and ate together, in keeping with Vision’s community ethos, and that’s how I found myself sat across from one of the most influential – and mysterious – bass players in the history of jazz: Henry Grimes.

Calm and quiet, he exuded an air of beatific detachment. As conversation bubbled around him, he peacefully ate his meal, with an enigmatic half-smile playing around his lips and a slightly faraway look in his eyes, while his wife, Margaret, did all the talking. I don’t think he spoke one word the whole time. Perhaps I should have expected as much. Back in 2010, I interviewed UK saxophonist Paul Dunmall, who was then playing in the Profound Sound Trio with Grimes and drummer Andrew Cyrille. He told me: “Henry doesn’t say too much. He’s a very quiet and gentle man. He loves to play, but he’s so gentle and introverted. He’s had an interesting life.” That’s something of an understatement, to say the very least.

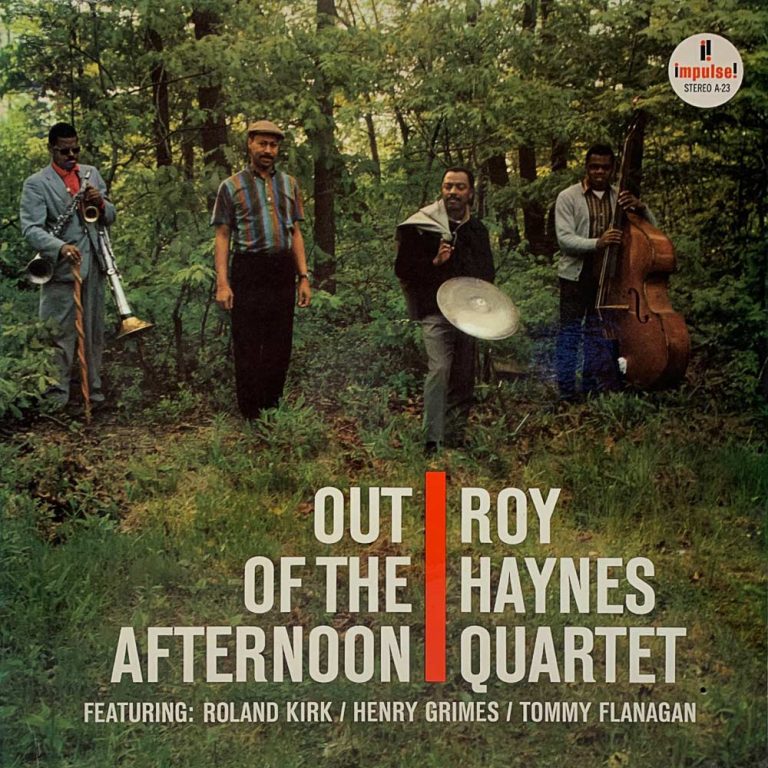

Born in Philadelphia in 1935, by the middle of the 1950s Grimes had emerged as a supremely skilled and versatile double-bassist. At the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958, aged just 22, he was in such demand that he performed with six different groups led by Benny Goodman, Lee Konitz, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Sonny Rollins and Tony Scott. By the beginning of the 1960s, he’d recorded with Konitz, Mulligan, Rollins, Mose Allison, and others – contributing to timeless albums including drummer Roy Haynes’ 1962 classic “Out Of The Afternoon”, and Sonny Rollins’ 1963 encounter with Coleman Hawkins, “Sonny Meets Hawk!”

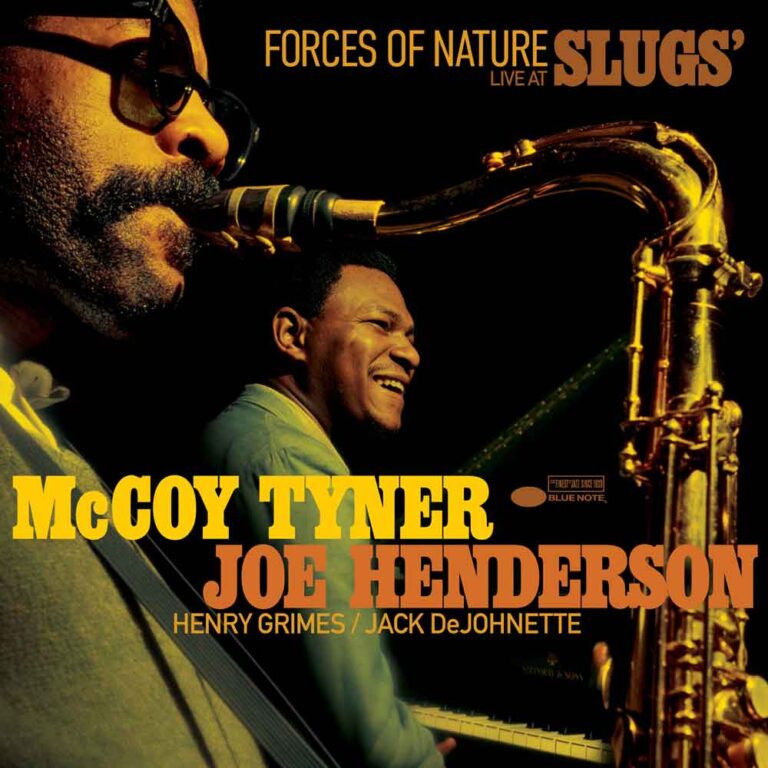

The same year, he recorded with Haynes as part of a hard-driving, blues-based piano trio, for McCoy Tyner’s second album “Reaching Fourth.” It was abundantly clear that Grimes was very much at home in this heavy-swinging, melodic milieu – as evidenced on the recently unearthed set from 1966, “Forces Of Nature: Live At Slugs,” which captures him in bullish mood on a furiously propulsive club date with Tyner, saxophonist Joe Henderson and drummer Jack DeJohnette.

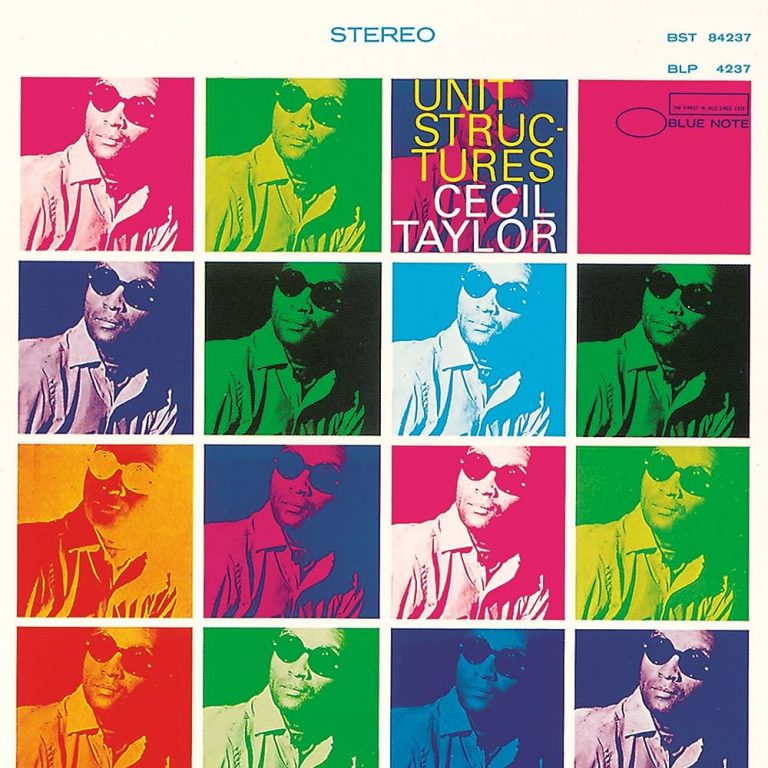

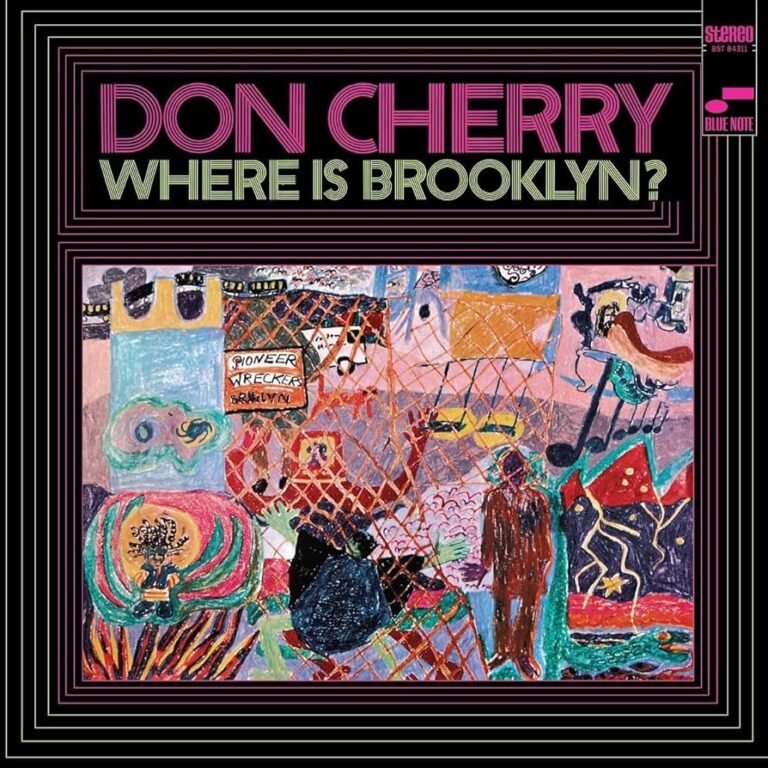

Yet, at the same time as he was making waves as a go-to straight-ahead bassist, Grimes was increasingly becoming fascinated by and active in the nascent New York free-jazz scene. As early as 1964, he recorded with Albert Ayler. In 1965 and 1966, he cut three definitive statements of the New Thing with Don Cherry, including the boisterous “Where Is Brooklyn.” Also in 1966, he contributed to two essential cornerstone recordings of free-jazz by Cecil Taylor – “Conquistador!” and “Unit Structures”. By the end of the 60s, further recordings with Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp – and an adventurous trio date under his own name, “The Call,” released by ESP-Disk in 1966 – had sealed his reputation as a key figure in the jazz avant-garde.

But then Grimes simply walked away from it all. Experiencing mental health difficulties, he found it increasingly hard to keep up with the fast-paced New York scene. In order to survive, he moved to California and began a long, lonely exile of sporadic homelessness and treatment for bipolar disorder. With all contact with the jazz world severed, many of his former musical associates assumed he had died. Then, in 2002, he was discovered by a fan, living in poverty in Los Angeles, writing poetry and just about getting by doing odd jobs. He was completely out of touch with his former life in music. He didn’t even know that Albert Ayler had died in 1970. But he was keen to play again.

Thus began one of the most remarkable comebacks of all time. Bassist William Parker donated a double bass to Grimes and, in 2003, after 30 years in obscurity, he began to perform again. He was enthusiastically welcomed as a returning hero by the avant-garde jazz community and made a triumphant appearance at the Vision Festival. Over the next 15 years, he toured and performed extensively, working with a pantheon of free-jazz greats including Rashied Ali, Marshall Allen, Bill Dixon, Roscoe Mitchell, John Tchicai and many others. He released seven more albums as a leader or co-leader and recorded other dates with the likes of Marc Ribot and William Parker. It was a glorious fulfilment of all his youthful promise.

This improbable third act finally came to an end in 2018 when the effects of Parkinson’s disease forced him to cease playing. Then, in 2020, aged 84, he died from complications of COVID. But his extraordinary life stands as a testament to resilience, to the unstoppable compulsion to create, and to the nurturing power of community. I just wish I’d asked him what he was thinking about when we were munching our rice and peas.

Read on…Jazz and India

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

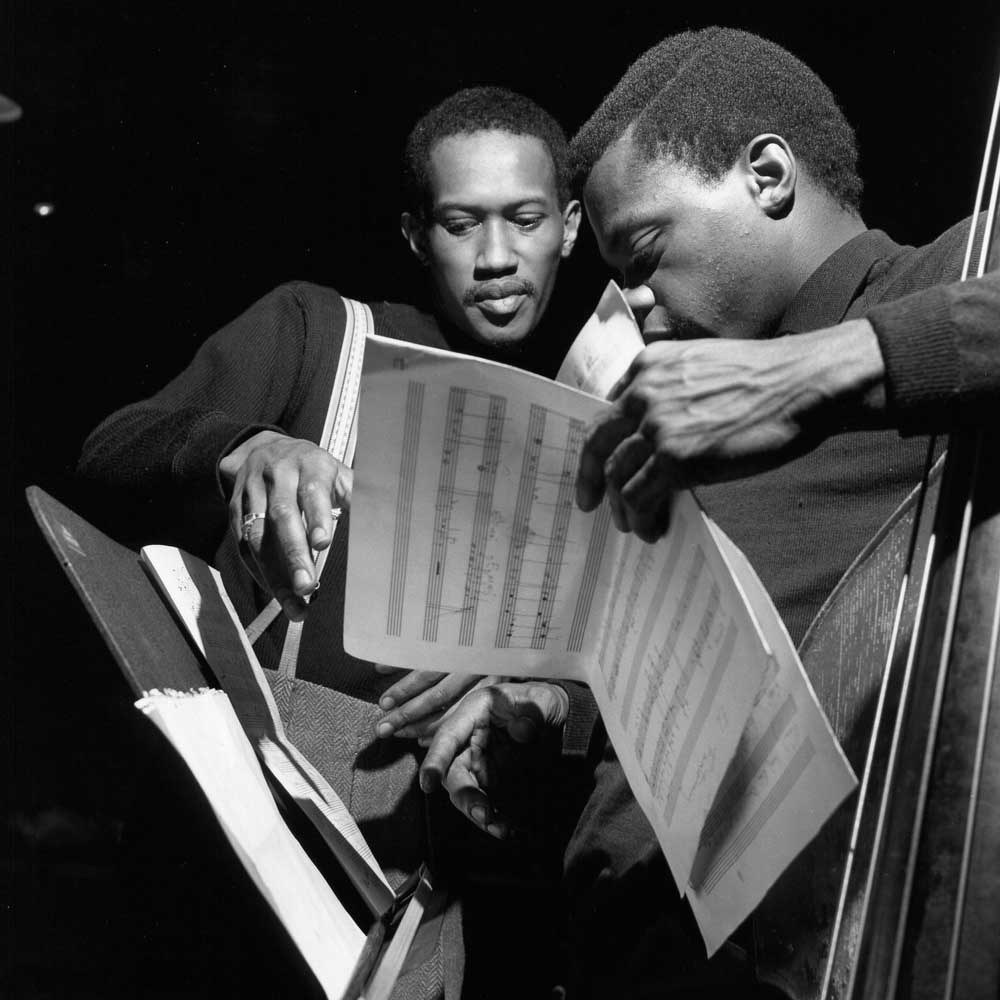

Header image: Henry Grimes. Photo: Alan John Ainsworth / Heritage-Images.