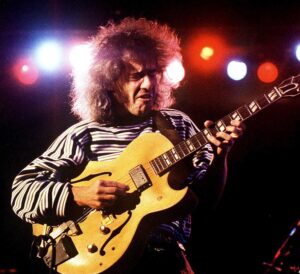

It is hard to believe that Pat Metheny, the ever ebullient, smiling and big haired virtuoso of jazz guitar recently turned seventy – he was still a teenager when he entered the studio as a sideman for vibraphonist Gary Burton’s 1974 album “Ring” for ECM.

ECM invited him to record his own debut as a leader, but Metheny took almost two years before committing to the sessions that would become “Bright Size Life” which would go on to become an historic record despite it being underappreciated on its release.

Recorded in Ludwigsburg at Tonstudio Bauer just outside Stuttgart in December 1975, it was produced by ECM co-founder Manfred Eicher.

Gary Burton’s influence on the record was profound. Eicher, who was trying to bring classical recording fidelity to jazz, wanted acoustic bass player Dave Holland on the session. Metheny told Rick Beato in 2022 that Burton was really the uncredited producer of the record. He remembered, “Gary was like, ‘Why would you want to use those guys when you’ve got this really great band with that bass player… you know that guy that you keep bringing up here [to Boston]?”

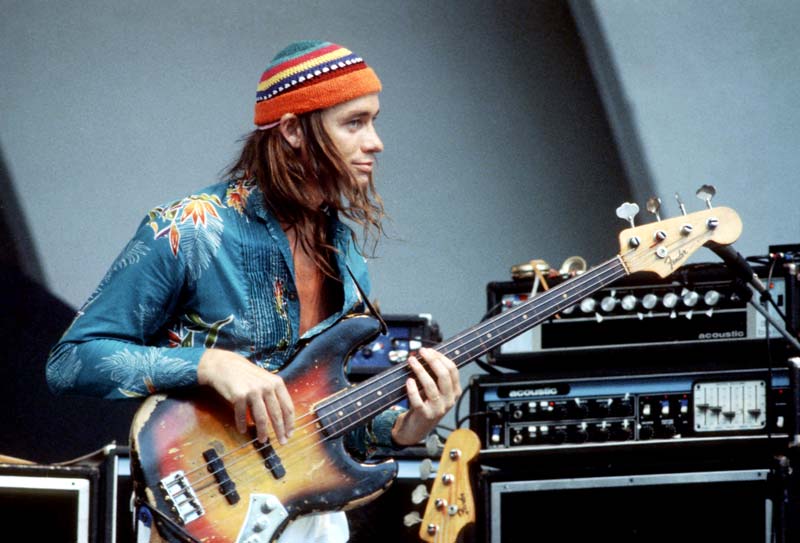

“That guy” was none other than bass virtuoso Jaco Pastorius who was largely unknown at the time. Metheny met Pastorius in Florida when he was studying at the University of Miami. “We would do gigs in Florida and we’d play with female impersonators for a week on Miami beach as the pit band.” Pastorius became part of Metheny’s regular touring band, he brought him to Boston with Bob Moses on drums who also played in Burton’s band. As a youngster Moses lived in the same building at 415 Central Park West, New York as Art Blakey, Max Roach and Elvin Jones.

Moses, who is now known by his spiritual name Ra Kalam (meaning ‘the inaudible sound of the invisible sun’) reflected, “The record doesn’t really represent how we played. That’s why I had a hard time listening to it for many years.” The interplay of Metheny’s cerebral harmonic virtuosity with Jaco’s strutting funkiness and Mose’s driving cymbal work and groove created a jazz equivalent of the power trios in rock.

The album was recorded quickly in just a couple of days, but the sessions were uncomfortable from the start: Pastorius almost missed the session because of jet lag – this was his first trip to Europe – and he didn’t have his usual Acoustic 360 amp to amplify his signature fretless electric Fender Jazz bass. Manfred Eicher was impatient with his precocious if soon to be appreciated talent.

“As far as I was concerned it was a disaster,” Metheny reflected, “we had played lots of gigs and we didn’t sound anything like what I was hearing coming back from the speakers… and beside that I just thought I sucked and I knew I particular… because on ‘Bright Size Life’ there was a big clam, I just messed it up.” Metheny was saved by an edit which is barely audible on the title track. He wasn’t alone; Bob Moses agreed “I don’t think I play that good.”

The ECM studio discipline might partially constrain the live energy of the band, but this recording established many of the unique elements Metheny’s oeuvre. All the pieces are written as vehicles for improvisation and follow the traditional bebop structure of head-solo-head, but they have complex elements that are signals of what was to come.

Metheny had been teaching at Berklee College of Music but his early life in Lee’s Summit, Missouri is also signalled on the album through composition titles like ‘Missouri Uncompromised’, ‘Omaha Celebration’ and ‘Midwestern Night’s Dream’. The latter is a good example of how Metheny used Pastorius’s fretless bass tone as a composition resource. The long melodic bass outro on Midwestern Night’s Dream was written by Metheny, and Jaco double-tracked the bass, defying the purist preferences of ECM’s Manfred Eicher. Bob Moses remembered “He did it in one take and it was like Wagnerian bass – two Jacos.”

In their different ways, both Metheny and Pastorius were expanding the tonal capacity of their instruments. The classic jazz guitar – the Gibson ES-175N – took on an expanded, haunting tone in Metheny’s hands, while Pastorius’ electric fretless bass created a radically new sound in jazz that has influenced so much of the popular music that followed.

While the album received lukewarm reviews at the time, it contained musical signals of where jazz was heading – be it in Jaco’s later landmark recordings with Weather Report or Joni Mitchell’s “Shadow and Light” live album that featured Pastorius and Metheny.

“When Bright Size life came out in ’75”, Metheny told Willard Jenkins in a interview 2017, “nobody really gave a shit about that record. Now it seems to have way more of a place than it did at the time. In fact it was listed in the Smithsonian as one of the hundred records of the 20th century… I am like, man when that guy in Downbeat gave it one star he didn’t see it that way! So, I say to young guys just do your best and play the music you love. It’s that thing of being yourself in the music – it may take fifty years for people to get hip to that.”

Read on… How the Jazz Guitar Found Its Voice

Les Back is a sociologist at the University of Glasgow. He has authored books on music, racism, football and culture, and is a guitarist.

Header image: Pat Metheny. Photo: Brian Rasic/Getty Images.