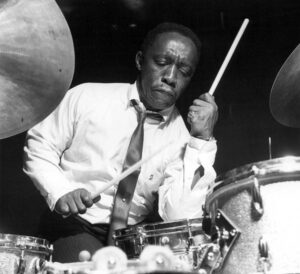

Following its emergence in the mid-1950s, drummer Art Blakey’s powerhouse unit, The Jazz Messengers, quickly developed a reputation as not only one of the preeminent hard-bop bands of the day, but also a proving ground for younger players. Blakey, who was born in 1919 and first made a name for himself in the 1940s in big bands led by Fletcher Henderson and Billy Eckstine, ran his group as equal parts boot camp and academy, providing a space where up and coming jazz musicians could hone their chops and develop their skills as composers before moving on to front their own outfits. In the sleeve notes to his 1961 Blue Note release, “A Night In Tunisia,” Blakey stated: “I always try to develop band leaders in my group. Why should I try to keep the fellows with me? Let them grow and form more good jazz groups.”

ART BLAKEY & THE JAZZ MESSENGERS A Night In Tunisia

Available to purchase from our US store.By the time of this album’s release, The Jazz Messengers had already included such luminaries as Horace Silver, Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham and Donald Byrd. But the quintet that recorded “A Night In Tunisia” arguably boasted the most talented players ever to play with him: tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, trumpeter Lee Morgan, pianist Bobby Timmons and bassist Jymie Merritt. With all but Merritt a full generation younger than Blakey, and all destined for later greatness, these musicians spearheaded perhaps the group’s most artistically fruitful period, recording some of its most enduring albums. It’s a measure of Blakey’s faith in them that four of “A Night In Tunisia’s” five tracks were composed by this youthful cohort, each revealing their individual strengths.

Taken at a buoyant, mid-tempo clip, Wayne Shorter’s “Sincerely Diana” slides in with an oblique, somehow mysterious melody that already hints at the progressive directions in which Shorter would take hard-bop with his classic mid-60s Blue Note albums. Here too, Shorter’s solo displays the insouciant inscrutability that became his signature sound. Bobby Timmons’ “So Tired” is a slinky soul-jazz boogaloo with a catchy head and an irresistible forward motion that encourages both Shorter and Morgan to unpack dazzling solos, with Morgan in particular bursting with muscular agility. Morgan supplies the album’s last two pieces: “Yama” is a deliriously lazy blues with a hint of melancholy, while “Kozo’s Waltz” is, as the name suggests, in a freewheeling ¾ time driven by Merritt’s nimble bass variations.

But it’s the album’s opening title track that steals the show: a glowering, 11-minute version of Dizzy Gillespie’s famous slice of bebop exotica. Written in the early 1940s, Blakey claimed to have first heard it while he and Gillespie were both members of Billy Eckstine’s band, and Blakey’s arrangement had long been a show-stopping feature of Jazz Messenger gigs.

In fact, Blakey had already recorded it in 1958 for the Vik label, on an album also entitled “A Night In Tunisia,” featuring the only recorded instances of saxophonists Jackie McLean and Johnny Griffin playing together. By 1961, it was a key Jazz Messengers track and, here, it positively burns with authoritative energy.

Beginning with Blakey’s booming tom rolls and punctuating cymbal crashes, it quickly slots into a heavy and densely polyrhythmic drum pattern powered by Merritt’s driving bassline and other Messengers adding chirruping claves and shakers, summoning a sweltering, North African, nocturnal scene.

Timmons introduces a lilting piano vamp, Shorter wafts in with a dark supporting sax figure, before Morgan states the main theme with audacious, richly ornamented brio. A sudden drop into a brief swing section of the chorus fully reveals its daring tempo and a fiery fanfare opens the way for extended solos from all until, around halfway through, a return to the thickly percussive undertow paves the way for a thumping solo from Blakey in the driving seat. Finally, brief, unaccompanied solo codas from Morgan and Shorter herald an explosive crescendo. It’s an unforgettable journey.

Blakey would go on to record a sprawling, 18-minute version of the composition again in 1979 for another album of the same name by a later iteration of the Jazz Messengers. But it’s this 1961 Blue Note version, in all its furious glory, that remains the definitive take, and a timeless hard bop classic.

Read On…Art Blakey – First Flight to Tokyo

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Art Blakey. Photo: Francis Wolff / Blue Note Records.