For decades, Jutta Hipp’s story was one of the big mysteries in jazz history. Nobody knew why the talented German pianist, who had emigrated to the US a few years prior, disappeared in the late 1950s.

“It just happened”, Hipp said in 1986, talking to jazz musician and historian Ilona Haberkamp, who wrote the only comprehensive biography about the reclusive legend. “I didn’t feel the urge to play anymore.”

That’s not the whole truth though. But to understand what really went down, we need to go back to the very beginning.

Hipp was born in 1925 in Leipzig, East Germany, and received classical piano lessons as a child. Though not allowed to listen to or even play American music in Nazi Germany, she discovered swing and jump blues over the radio.

After the war, she fled to American-occupied Munich. Sustaining herself by playing piano in G.I. clubs, she rose to fame in West Germany’s nascent music scene because of her distinct modern jazz style, heavily influenced by Lennie Tristano.

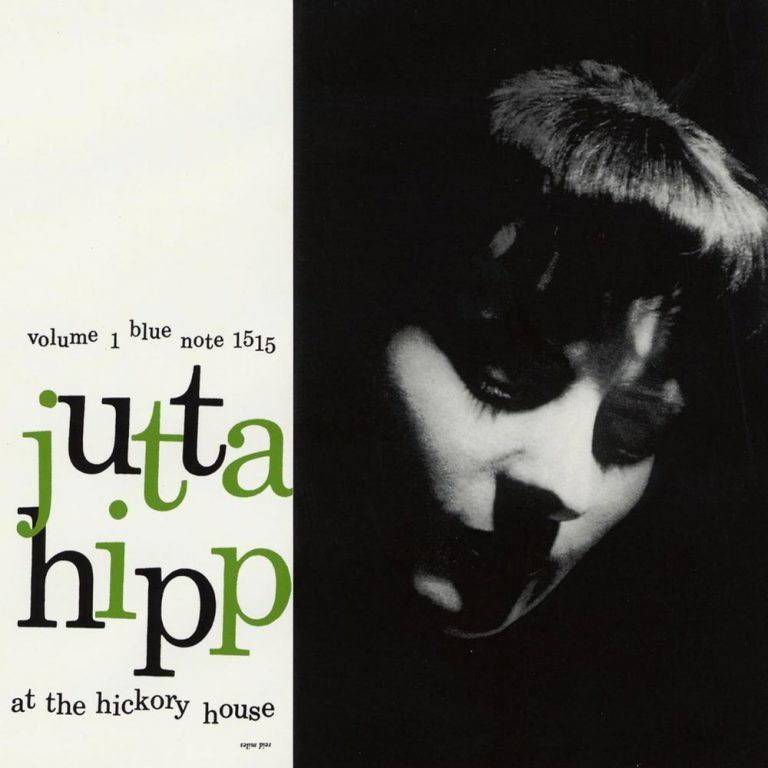

In 1954, the young talent was discovered by music impresario Leonard Feather in a jazz club in Duisburg, Germany. Taken by Hipp’s serious chops and austere beauty, Feather invited her to New York. He funded her first album recording for Blue Note, while she was still in Germany, waiting for her artist visa.

The next year, Jutta Hipp found herself in the midst of the Big Apple, as one of very few women on the jazz club circuit, and a white European one at that.

Impressed by hearing Horace Silver, she adapted to the new hard bop style that was en vogue in New York, combining it with her swing and jump roots and classical leanings.

Feather got her a residency at the Hickory House, a famed dinner restaurant where two trio albums for Blue Note were recorded live, with Peter Ind on bass and Ed Thigpen on drums.

That very same year, in 1956, Hipp recorded a full album with saxophonist Zoot Sims, whom she deeply admired. It looked like she had reached a high point in her career.

But the introverted musician struggled with self-doubt, depression, and loneliness. Experiencing misogyny and witnessing racism were prevalent in her daily life. The business of music didn’t appeal to her.

On various occasions, Art Blakey and Miles Davis behaved hostilely towards her. Hipp took that deeply personally, asking herself if she actually deserved her spot.

Having long since used alcohol to battle her low self-esteem, now her drinking spiralled out of control – and her behaviour became increasingly erratic. Over the next months, she lost the support of two powerful men, her manager Leonard Feather – who might have felt romantically rejected by her, as Haberkamp suggests – and her well-connected booking agent Joe Fraser.

By 1958, she found herself on her own, broke and on the verge of homelessness. When she took on a low-wage job as a seamstress in a clothing factory, it took a lot of pressure and stress off her shoulders. She still played on weekends, but slowly faded out of the scene, as she stopped drinking and couldn’t take jobs at night.

Somewhere around 1959/60, Jutta Hipp decided to leave the music world behind completely.

She later revealed that she started living a calm, reclusive life in a small Queens apartment full of books and records. For self-expression, she took up drawing and painting, which she had pursued and studied as a young woman in Germany.

Hipp worked in that clothing factory until she turned 70. She never married, but kept a few close friendships with people from the jazz world, mainly through letter exchanges.

In the 1980s, when she had been forgotten and written out of jazz history, her work was finally rediscovered and reissued. With the renewed interest in her 1950s work, she started giving interviews again.

Years later, Blue Note sent her a check over $40,000 in royalties – they had accumulated over decades, as her whereabouts were unknown. It was too late for her to enjoy affluence. She needed the money to pay for medical bills.

Aged 78, Hipp died from cancer in her New York apartment in 2003. She’d never visited Germany again. She had no contact with her son, whom she’d left for adoption. And she’d categorically turned down all offers to return to playing and recording.

Stephan Kunze is a writer and book author based in Germany. He writes the newsletter zensounds on music, culture and philosophy.

Header image: Jutta Hipp. Photo: Karl Ludwig Haenchen.