During the early 1960s, Blue Note had hit on somewhat of a formula: The 3 Sounds, Horace Silver and Art Blakey were decent-selling stalwarts, and there was also the emergence of a formidable set of young, progressive solo artists such as Andrew Hill, Larry Young, Bobby Hutcherson, Sam Rivers and Tony Williams. But there were murmurings of discontent from the jazz press and the label also had the avant-garde revolutions of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor to contend with (though both would of course later record for Blue Note).

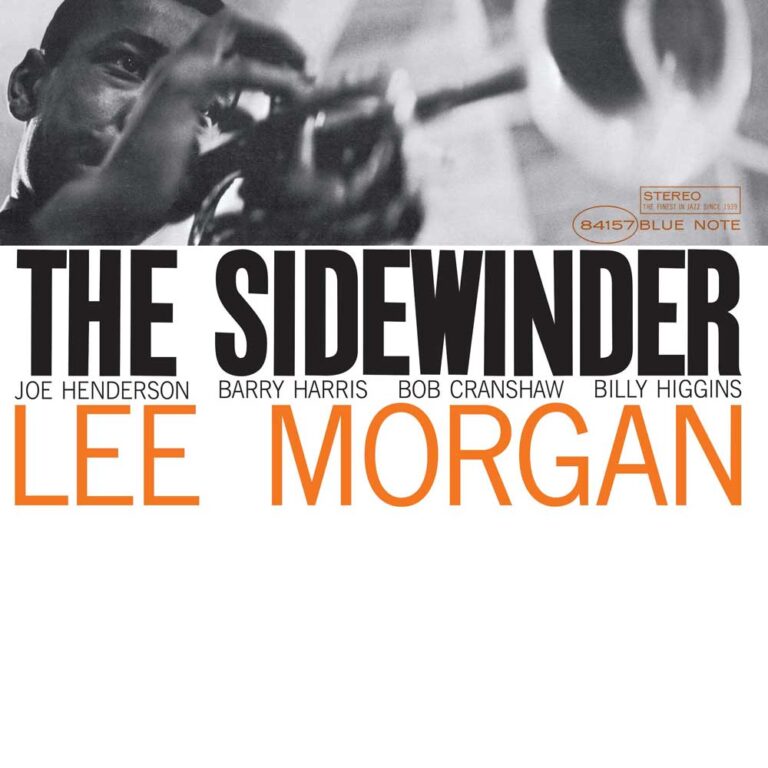

All of that changed courtesy of two classic hit singles: Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man” and Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder”. Morgan was another from Philadelphia’s rich jazz lineage, a thoroughbred, power trumpeter in that fine tradition from Buddy Bolden to Clifford Brown and beyond, and a member of Dizzy Gillespie’s fabled big band at the age of just eighteen. Lifestyle issues had led to a sabbatical from his Blue Note solo career and valued sideman gig with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, but “The Sidewinder” was a triumphant return to form.

Recorded, like the rest of its attendant album, on 21 December 1963, “The Sidewinder” is a classic soul-jazz composition, built on pianist Barry Harris’s watertight vamp and Billy Higgins’ ingenious boogaloo beat (comprising only ride cymbal and snare drum). It was also reportedly a last-minute addition to the album, Morgan hurriedly scribbling down the arrangement during a toilet break. The spontaneity produced palpable excitement among the players though, particularly Higgins – close listening reveals his excited vocal encouragement throughout the long piece.

It was released as a single, spread over two sides, reaching #81 on the Hot 100. It also became a massive jukebox hit. Right up until his death in 1972, Morgan would often end gigs with “The Sidewinder”, as heard on his classic “Live At The Lighthouse” album. It influenced legions of jazz players later in the 1960s too – even Miles, whose album “Filles De Kilimanjaro” and composition “Stuff” clearly owe it a debt. It has also been subjected to numerous cover versions, perhaps the weirdest by New Directions, a 1999 Blue Note supergroup featuring Greg Osby, Jason Moran and Stefon Harris.

But the whole album is crammed with memorable themes, all written by Morgan: “Totem Pole”, featuring an all-time great tenor sax solo by Joe Henderson, has echoes of the Dizzy Gillespie sound, while Morgan delivers some awesome call-and-response figures on “Gary’s Notebook”. “Boy What A Night” has a Charles Mingus flavour courtesy of its driving 6/8 feel and pile-driving Bob Cranshaw (misspelt on the album cover) groove while Higgins delivers another classic beat on “Hocus Pocus”, underpinning one of Morgan’s most elaborate, attractive melodies.

The album reached #25 in the Billboard charts – it was a sales phenomenon that proved somewhat of a first-world problem for Blue Note owners Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff. Distributors clamored for more hits. Radio and print advertising became more prevalent and suddenly one might see Blue Note albums in Mom and Pop stores. But arguably the label also started looking for a “Sidewinder” on every album, with diminishing returns.

But nothing can diminish the sheer infectiousness of this evergreen album, exemplified by the fact that the US Library of Congress recently added it to the National Recording Registry, deeming it “culturally, historically, and/or aesthetically significant”.

Matt Phillips is a London-based writer and musician whose work has appeared in Jazzwise, Classic Pop, Record Collector and The Oldie. He’s the author of “John McLaughlin: From Miles & Mahavishnu To The 4th Dimension”.

Header image: Lee Morgan. Photo: Francis Wolff / Blue Note Records.