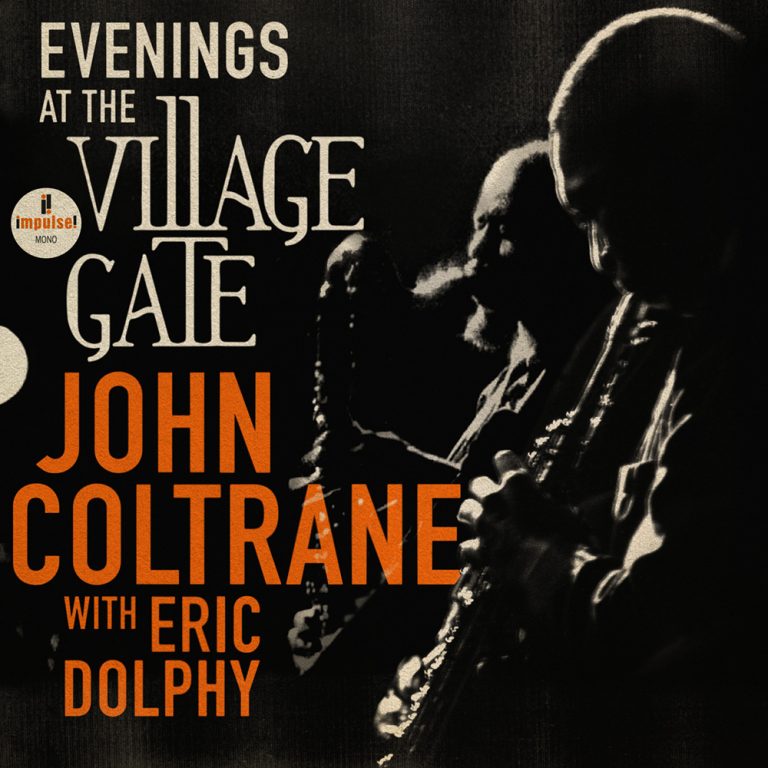

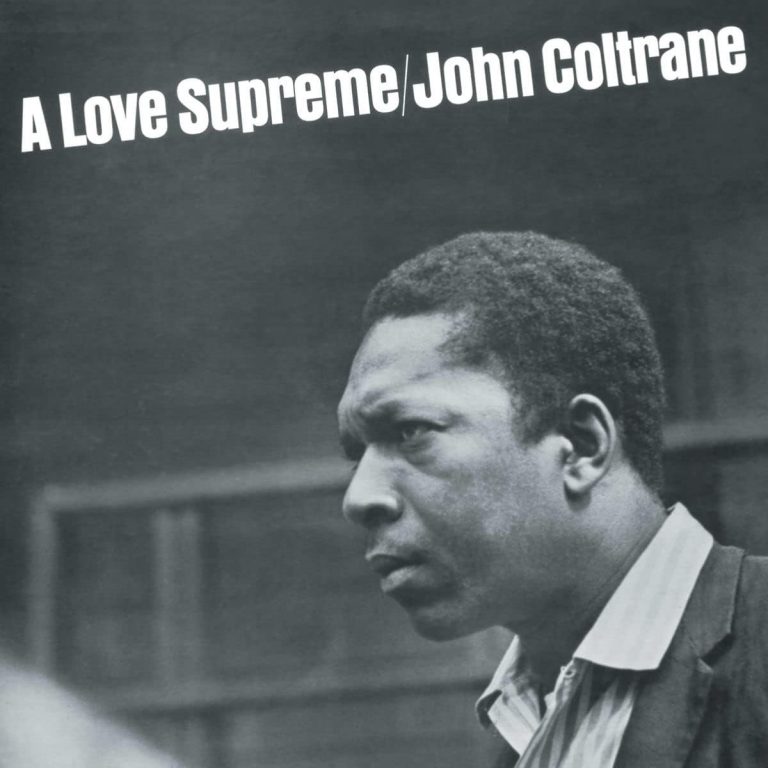

The arrival this summer of “Evenings At The Village Gate: John Coltrane With Eric Dolphy” provides a stunning opportunity to hear previously unreleased recordings of the legendary saxophonist John Coltrane playing in a New York jazz club in summer 1961. It’s also a chance to catch him in a restless period of transition, exploring ideas that would take shape as his music evolved with astonishing speed and intensity in the following years.

1961 was the year Coltrane began to experiment with expanded line-ups, moving beyond the quartet configuration that had formed the backbone of previous recordings, and incorporating extra musicians to provide a wider sonic palette. On “Evenings At The Village Gate,” we hear his short-lived quintet featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Reggie Workman, drummer Elvin Jones and multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy on alto sax and bass clarinet – plus, on the only known non-studio recording of “Africa,” the addition of second bassist Art Davis. This was part of Coltrane’s desire to move beyond hard-bop and investigate modal jazz, African influences and the fringes of the new free jazz that had begun to inspire him. Aided by Dolphy’s idiosyncratic, often challenging approach to melody, he was determined to break new ground.

Fast forward to 1965, and Coltrane’s ideas had blossomed into even more unexpected shapes – as witnessed first-hand by drummer Terry Clarke, who today holds the distinction of being one of very few surviving musicians to have shared a stage with Coltrane. Originally from Vancouver, in 1965 20-year-old Clarke was living in San Francisco and playing in the quintet led by alto saxophonist John Handy. Like so many musicians of his generation, his own approach to music had been profoundly impacted by Coltrane’s output. “I was consumed with that band,” he recalls. “For two, three years before I moved, that’s all I listened to. We were all trying to play “Impressions” and “Afro Blue.” When “My Favorite Things” came out, that just levelled all of us, it was so beautiful. We would just devour all that.”

So, when Coltrane came through San Francisco for a week-long engagement at the Jazz Workshop in September that year – the same month Handy’s band cut its critically acclaimed album “Recorded Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival” – Clarke, Handy and bassist Don Thompson made sure they were there in person. But, if they were expecting to catch Coltrane playing with his classic quartet featuring Tyner, Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison, they were in for a shock: by this time, the band had swollen to include young firebrand Pharoah Sanders on second tenor saxophone and additional bassist Donald Garrett. And it wasn’t just the line-up that had changed. “The music was transitioning then,” says Clarke. “It was free – completely free music – and that was a surprise to me because I was still in love with the way they had played maybe six months before. It was changing so fast that I don’t know if I really liked it, but I was willing to listen.” As it happened, he got to do much more than just listen – when Elvin Jones invited him to sit in on drums for a tune. Though Clarke initially declined the offer, events were taken out of his hands: “I got pushed up on the bandstand,” he chuckles.

“John Coltrane started playing with me, in time, and took off. The feeling he played with was absolutely astonishing. It was so effortless”

Terry Clarke

What happened next is indelibly etched in his memory: “They started to play free again and I didn’t quite know how to do that, so I started playing a tempo, which was kind of against what they were already doing. Within about a millisecond, John Coltrane started playing with me, in time, and took off. The feeling he played with was absolutely astonishing. It was so effortless. McCoy was on my left and even he started reluctantly playing some rhythmical figures against what I was doing. Jimmy Garrison joined in and we played that way for a while. I just played my ass off. It was 10 minutes of my life, but it felt eternal. I can still feel what it felt like. There I was, playing this drum set that I’d been listening to for years. It was completely overwhelming.”

For Clarke, it wasn’t just a musical adventure. It was also a chance to experience the great generosity of spirit that Coltrane famously extended towards younger players. “John was beginning to feel that he wanted to invite everybody to play, like it’s a family,” he recalls. “Everybody was welcome to come up and play. This kind of communal thing was beginning to happen. Another guy jumped on the drums right after me and after he left maybe another guy. John wanted everybody to be involved. He was a very soft-spoken man. He’d walk in the room and all of a sudden everything got calm. That’s what was on the bandstand. He was a very gentle soul.”

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

Header image: Francis Wolff Collection / Blue Note Records