Freya Hellier: Brandee Younger’s “Brand New Life” (Impulse!)

Back in the nascent days of Everything Jazz, I remember chatting with my co-editor Stephan Kunze about Dorothy Ashby. It seemed that everyone was talking about her and getting into her music, even though she had passed almost 40 years earlier. It felt worth writing about, so we declared 2023 the year of jazz harp, and I got to work on a feature for our launch in June. Six months on, we have three harpists in our albums of the year round up – our hunch was a good one.

Dorothy Ashby was the gateway to my choice: Brandee Younger. The young New York harpist makes no secret of her admiration for Ashby, but in Younger’s “Brand New Life” – her second album for Impulse! – she establishes a vibrant dialogue with Ashby’s music that keeps the portal between the two harpists wide open. Younger’s homage does more than honour Ashby’s music, “Brand New Life” lays out a tantalising trail of musical breadcrumbs for listeners to build a deeper understanding of the two musicians.

“Livin’ and Lovin’ In My Own Way” is one of two previously unrecorded Ashby compositions brought to light by Younger, and it features Pete Rock, one of the first hip-hop producers to sample Ashby’s music. The other is the beautifully romantic opening track “You’re A Girl For One Man Only”. Younger’s effortlessly sweeping harp combines with the counterpoint of Rashaan Carter’s bass and Joel Ross’ swirling vibes to create a deep, hypnotic river on which to set the rest of the album afloat.

The title track “Brand New Life”, co-written with vocalist Mumu Fresh, is an ethereal, yet deep groove reminiscent of the Soulquarian era, and “Dust” featuring Meshell Ndegeocello (Younger returned the favour of Ndegeocello’s album “The Omnichord Real Book” – also one of our albums of the year) is a vibe-heavy rework from Ashby’s 1969 album “The Rubáiyát of Dorothy Ashby” (which is, you’ve guessed it, another of our albums of the year).

When we spoke earlier this year, I asked Brandee about the strong sense of collaboration on the record, and she told me: “The whole process of doing this recording was super special. We recorded it in Chicago at Makaya McCraven’s house, so Makaya produced the whole record. And my favourite albums of Dorothy Ashby’s were recorded in Chicago on the Cadet label, where Richard Evans produced it. So it was it was really cool to be able to, I call it having the Chicago grease on the record by getting it done in Chicago, in such a comfortable environment with Makaya on drums and Rashaan Carter on bass, just the three of us working out the core of the whole record which was really, really, really special.”

It’s no wonder Brandee Younger feels such kinship with Dorothy Ashby – both women have championed and extended the reach of the harp within jazz, and both are the go-to collaborators for the music icons of their day (Ashby worked with Stevie Wonder, Bill Withers, Bobby Womack, Minnie Riperton; Younger with The Roots, Common, Lauryn Hill). Whether it’s through extensive sampling by hip-hop producers (as in Ashby’s case) or via genre-fluid collaborations that Younger clearly revells in, the harp sits at the centre of many musical crossroads.

Freya Hellier is a content editor for Everything Jazz. Based in London and Glasgow, she has spent many years making programmes about all genres of music for BBC Radio 3, Radio 4 and beyond.

Daniel Spicer: Kenny Cox’s “Introducing KennY Cox” (Blue Note Classic Vinyl)

No matter how well you think you know jazz, there are always unknown treasures to be found. One of the albums I’ve enjoyed discovering this year is the 1968 Blue Note debut by pianist Kenny Cox and his quintet featuring Charles Moore on trumpet, Ron Brooks on bass, Danny Spencer on drums and, on tenor sax, Leon Henderson, younger brother of tenor legend Joe Henderson. The music they make owes a very clear stylistic debt to that of Miles Davis’s Second Great Quintet with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams. Fans of Miles’s sophisticated and assured mid-to-late 1960s sound will surely dig the strong compositions and commanding group interaction of Cox’s Contemporary Jazz Quintet.

But it’s more than just a homage. Cox was a native of Detroit and his young band (all between the ages of 26 and 33 at the time of recording) were pretty much unknown outside of the Motor City. Blue Note’s producer extraordinaire, Duke Pearson, actually travelled to Detroit to record them, setting up a session at which the quintet cut six tracks they’d worked out during the year or so they’d been together. The music that finally made it onto Introducing Kenny Cox and the Contemporary Jazz Quintet zings with both a hungry, youthful energy and a hard-edged feel that conjures the gritty reality of life in blue-collar, industrial Detroit.

Album opener, Cox’s “Mystique,” is a tough, uptempo, bebop-influenced swinger powered by Spencer’s racing ride cymbal and Brooks’ furiously walking bass. The quintet sound utterly at home at this galloping pace, and they turn the heat up even more on the breakneck post-bop of “Eclipse”, written by Henderson. Here, there’s a clear nod to Miles, with a brief, fanfaric head giving way almost immediately to blazing solos.

But there are other moods too. “You” is slow and reflective yet maintains a toe-tapping momentum throughout. Cox’s “Trance Dance” is a muscular soul-jazz vamp hung on a riff with just a hint of the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction.” “Number Four,” written by Moore, is the longest track on the album at nearly 11 minutes, giving the soloists room to stretch out while Spencer holds down a metronomic, almost mechanistic hi-hat clip. Henderson’s “Diahnn,” is a gentle, sparse ballad, bringing the album to a meditative close.

Cox’s Contemporary Jazz Quintet would cut just one more album for Blue Note, 1969’s Multidirection, after which Cox went on to found the short-lived Detroit-based Strata record label and record with an even grittier, electric sound. Somehow, he never quite fulfilled the enormous promise shown on his Blue Note debut – but we’re lucky that it’s still in print, just waiting to be discovered by the curious listener.

Daniel Spicer is a Brighton-based writer, broadcaster and poet with bylines in The Wire, Jazzwise, Songlines and The Quietus. He’s the author of a book on Turkish psychedelic music and an anthology of articles from the Jazzwise archives.

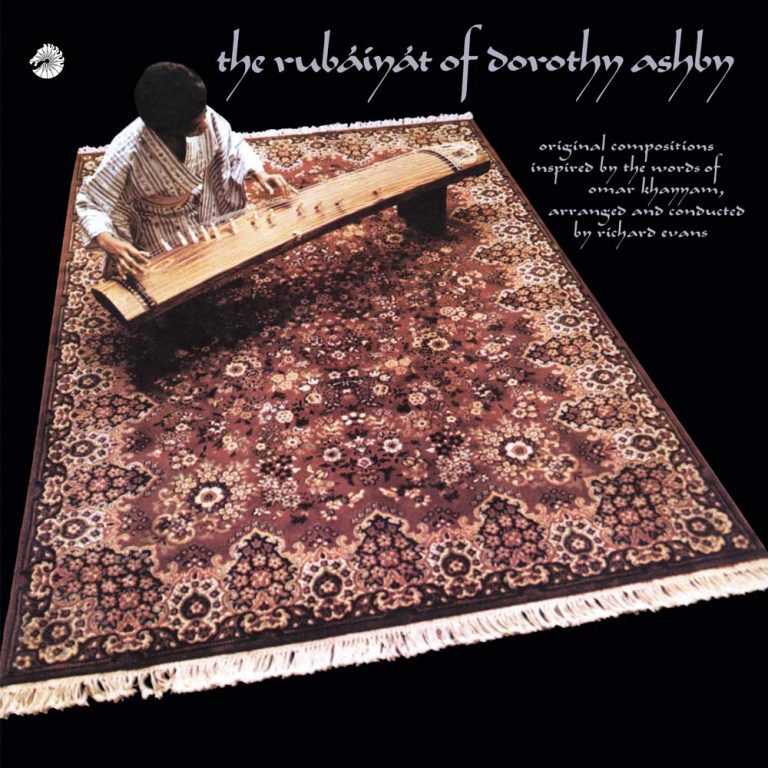

Jane Cornwell: Dorothy Ashby’s “The Rubáiyát Of Dorothy Ashby” (Verve bY Request)

A glistening cascade of harp strings, a wash of sparkling ethereality, and we are through a portal into an otherworld. A soundscape where a female voice – rich, amber, almost operatic – sings ancient words about searching for answers to life’s fundamental questions. Propelled, too, by duelling flutes, encased in flowing, sometimes epic arrangements, the four-line stanzas known collectively as rubaiyat seem to shimmer with a tranquil yet vaguely ominous spirituality. ‘Their words to scorn are scattered, and their mouths stopped with dust,’ emotes Dorothy Ashby, for it is she, running her fingers through her harp, plucking at her Japanese kyoto-zither, singing with funky, surprisingly Bassey-esque flair.

Recorded in 1969 and released in 1970, “The Rubáiyát of Dorothy Ashby” is a concept album that unfurls like a Damask rose. More multilayered than Afro-Harping, the 1968 opus that made the Detroit artist’s name, Ashby’s ninth and penultimate album bathes in the mysticism beloved of the era’s counter-culture, folding soul-funk and cosmic jazz into lyrics by 12th century Persian poet and philosopher Omar Khayyam. Chicago soul arranger Richard Evans, producing, channels an aesthetic already polished by his work with Natalie Cole and Ahmed Jamal and a brief stint in Sun Ra’s Arkestra, bringing in instruments including vibes, flutes, kalimba, guitar and his own Soulful Strings project. The resulting sound is less jazz than soul-funk, maybe early jazz-fusion. If you love Earth, Wind and Fire (and do I ever) then you’ll love the way this grooves.

One of its many USPs is Ashby’s sometimes angular, sometimes circular but always evocative koto, Japan’s national instrument, whose genteel but ghostly air reinforces its ancient reputation as a conduit for spirit-voices, and which she integrates into the jazz idiom in ways bold and inventive, arguably helping redefine her identity away from that of Alice Coltrane, with whom she was frequently compared. There’s the presence of spoken word artist Rafiyq, lend stentorian gravitas and civil rights verve to several of Khayyam’s epigrams. There’s the pleasure of hearing Ashby, previously known only for her harp skills, sing or speak the words; of feeling her push boundaries with the confidence that accompanies talent, relishes risk-taking.

Highlights are many: a slice of celestial soul covered by the likes of Brandee Younger, “Wax and Wane”, that finds kalimbas playing counterpoint rhythms and Ashby’s harp vying and blending with hurtling percussion. “Shadow Shapes” melds genres as it glitters with melodic invention; “For Some We Loved” is buoyed by trance-like drum patterns from an in-the-pocket rhythm section; “The Moving Finger” begins with what might be a Japanese Buddhist chant before instrumentalists fall in with increasing urgency and an explosive fuzz guitar solo takes things through another portal, into outer space. “The Rubáiyát of Dorothy Ashby”, then: music from the future, even now.

Jane Cornwell is an Australian-born, London-based writer on arts, travel and music for publications and platforms in the UK and Australia, including Songlines and Jazzwise. She’s the former jazz critic of the London Evening Standard.

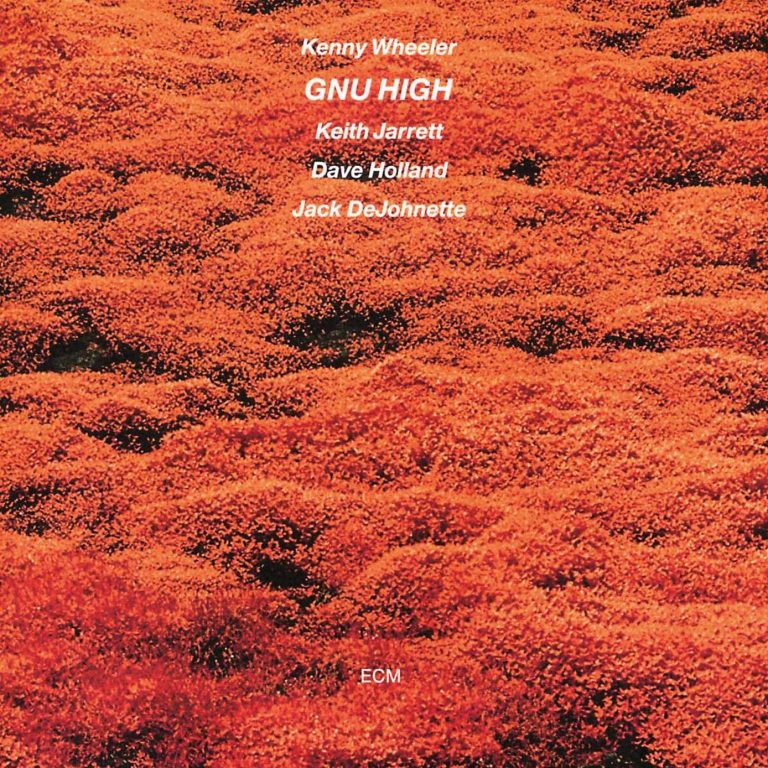

Matt Phillips: Kenny Wheeler’s “Gnu High” (ECM Luminessence)

1975 and 1976 were landmark years for ECM Records with vital releases from Keith Jarrett (“The Köln Concert”), John Abercrombie (“Gateway”), Gary Burton (“Dreams So Real”) and Pat Metheny (“Bright Size Life”). But Kenny Wheeler’s “Gnu High” – lovingly re-released during 2023 as part of the label’s Luminessence audiophile vinyl series – also belongs in that illustrious company.

Recorded at New York City’s Generation Sound Studios in June 1975, “Gnu High” was the first ECM solo album from the highly original Canadian trumpeter and flugelhornist, known for his fly, skittering improvisations and rum, memorable compositions.

Conversations with producer/ECM owner Manfred Eicher led Wheeler to suggest two pianists for the session – Chick Corea and Jarrett. Both veered towards the latter, but there was one problem – by 1975, Jarrett wasn’t really doing “sideman” gigs. Eventually, some gentle persuading from Eicher secured Jarrett for the “Gnu High” session, the pianist reportedly only setting eyes on Wheeler’s scores a few hours before the tape rolled.

What emerged – also in the company of simpatico rhythm section of Dave Holland on bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums – was nothing less than a triumph. It’s clear from the opening four bars of “Heyoke” that this album is going to be very special, with DeJohnette’s extraordinary “floating” sense of time, Wheeler’s stately, memorable composition and Jarrett’s rhapsodic contributions (though, according to Ian Carr’s classic Jarrett biography, he was neither particularly happy with his playing nor Wheeler’s music). The whole album also has a “larger than life”, epic quality, no doubt helped by the contributions of engineer Tony May and legendary ECM mixer Martin Wieland.

“Gnu High” was the beginning of a prodigious ECM career for Wheeler, who died in 2014. And the album title? The dryly humorous Canadian was very fond of word games – a “gnu” is a type of wildebeest…

Matt Phillips is a London-based writer and musician whose work has appeared in Jazzwise, Classic Pop, Record Collector and The Oldie. He’s the author of “John McLaughlin: From Miles & Mahavishnu To The 4th Dimension”.

Header photo (from left): Brandee Younger. Photo by Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images. Kenny Wheeler. Photo by David Redfern/Redferns. Dorothy Ashby. Photo by Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy.