John Coltrane is the unrivalled titan of the saxophone, the man who drew every conceivable sound from his horn. He pushed his ‘classic quartet’ to unprecedented musical achievement in the mid 1960s, creating a body of work that was so compelling it seemed frankly nonsensical to think that the band needed an additional member.

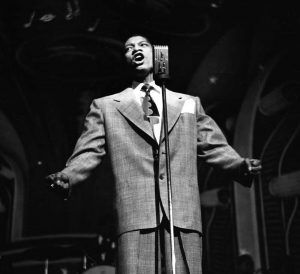

Yet it would find its ‘fifth Beatle’ in front of a silver ribbon mic. He was Johnny Hartman, a man with a baritone so plush and phrasing so seamless he sounded like a ship gliding on the stillest of waters. On “John Coltrane And Johnny Hartman,” the singer brings a current of love-struck joy and forlorn melancholy to masterpieces such as “Lush Life,” where he beckons Coltrane’s tenor to drift into life, like warm breath around the world-weary words, before the saxophonist stirs into a long, lustrous solo.

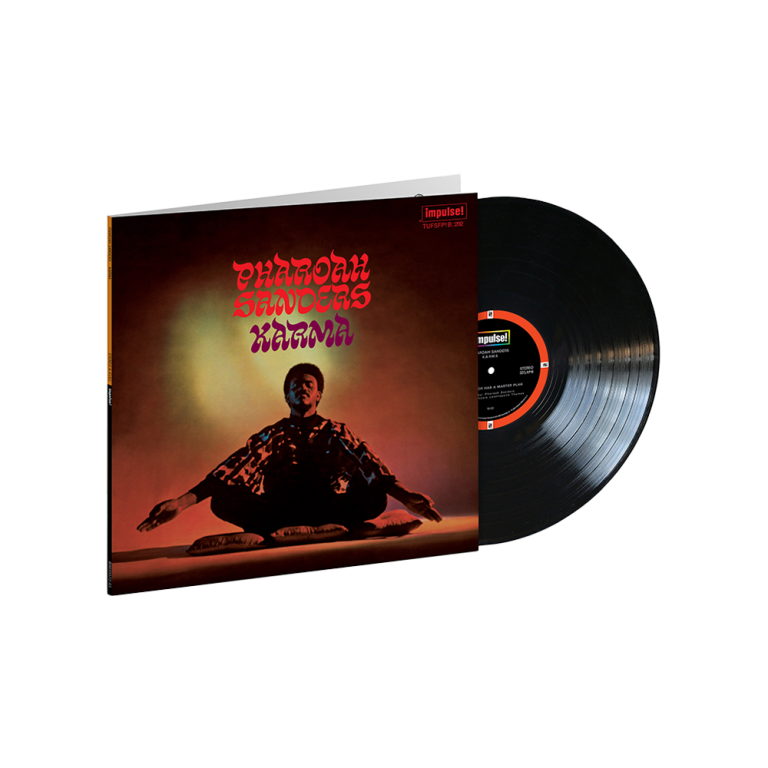

Coltrane and Hartman set a high bar for their successors. Yet many saxophonists have struck up engrossing relationships with singers since, the key example being Coltrane protégé Pharoah Sanders, who created timeless spiritual meditations with Leon Thomas in the 1970s. Between the 1980s and 2000s Courtney Pine worked with vocalists as accomplished as Susaye Greene, Cassandra Wilson and Carleen Anderson. As for Joe Lovano, he has made some outstanding music with his wife Judi Silvano.

But those are all cases of a singer who guests with a player on one or two songs. Projects where they have joint billing are fascinating because any putative hierarchy disappears. Think Cannonball Adderley and Nancy Wilson’s absolutely sumptuous collaboration, which was titled “Nancy Wilson And Cannonball Adderley” rather than Cannonball Adderley And Nancy Wilson. The lady played second fiddle to no man.

Then again you could run the same line about Billie Holiday and Lester Young.

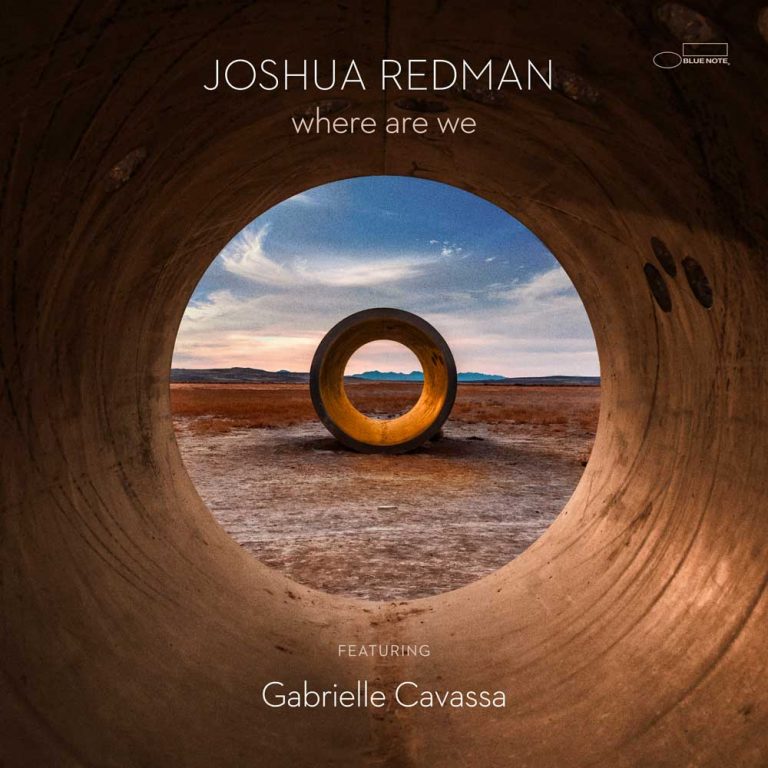

This year Joshua Redman, a notable contemporary keeper of the saxophone flame, made an excellent album, “where are we,” that introduces the talented young singer Gabrielle Cavassa. The California born New Orleans based vocalist is an integral part of a stellar multi-generational band that includes peerless drummer and longstanding Redman collaborator Brian Blade as well as the excellent pianist Aaron Parks.

Her name is on the sleeve of the record, albeit below Redman’s, who is clearly the designated leader, but nonetheless it is there, ensuring that Cavassa registers in the mind of any potential listeners as soon as they lay their eyes on the distinctive picture of an expanse of blue sky spied through a circular ochre tunnel. If the image evokes wide open spaces then the premise of the music is the cultural-historical sweep of America by way of its great cities that have all been enshrined in song. Think “Streets Of Philadelphia,” “Baltimore,” ‘“By The Time I Get To Phoenix,” and “Alabama.”

It is tempting to say that Cavassa makes the music more accessible. She is singing lyrics after all, lending explicit meaning to themes that would be more open to interpretation if they were purely instrumental. That only tells half the story though. Words notwithstanding there is the timbre, character and colour spectrum of the voice to consider, or, more to the point, how it coheres with the overall musical setting. There is a delicacy, an almost misty quality in the soft stretch of Cavassa’s line endings that makes them flow enticingly into Redman’s legato sighs, the combined effect of which is quietly powerful on “Chicago Blues.”

Interestingly, this gem is from the songbook of big band legend Count Basie, and was co-written with one of his key crewmembers: not a horn player or a drummer, but a singer, the wonderful Jimmy Rushing, whose immense depth of feeling earned him the sobriquet “5 Feet Of Soul.”

The emotional charge generated by Cavassa and Redman is no less intense, though it is more of a flicker than a fire, which makes it clear that the same song can take on an entirely different guise in different hands – and mouths. In 1960 Rushing also made a superb album with pianist Dave Brubeck, highlighting that the chemistry Rushing enjoyed with Basie’s orchestra could exist in a far less brash, brassy quartet setting.

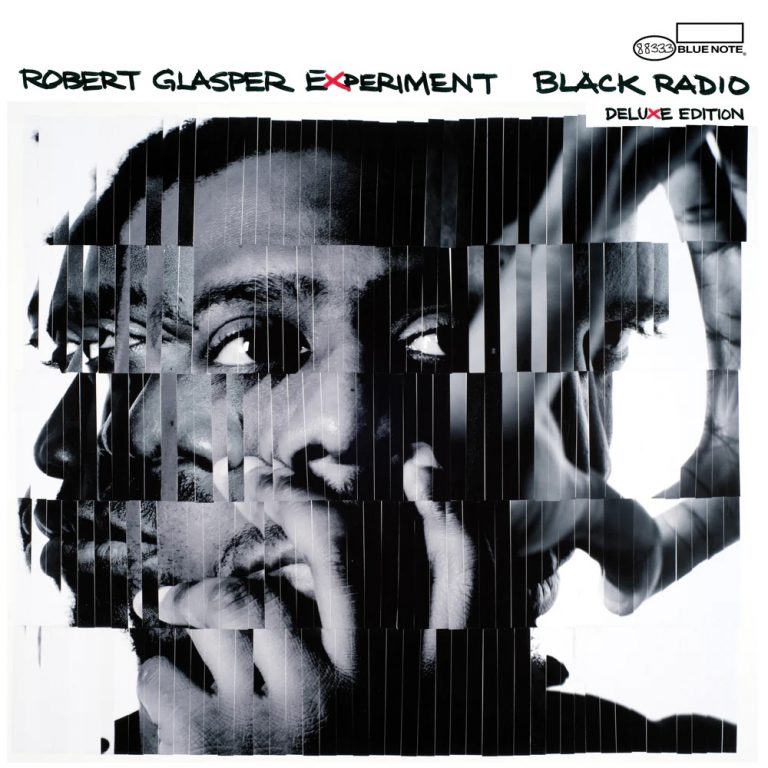

Jump to the 1990s and 2000s and we see more incumbents putting a new slant on the pianist-vocalist union: Hank Jones and Abbey Lincoln; Chick Corea and Bobby McFerrin; Laurence Hobgood and Kurt Elling; Robert Glasper and Bilal Oliver.

In each case, the beauty of the music stems from the ability of one artist to tune into the emotional wavelength of the other, and think, feel and perform as one, all the while retaining their individualism. It’s a balance to strike. When Glasper and Oliver perform “Maiden Voyage” they tread with the same measured steps as other players and singers who hit the sweet spot where one just cannot be heard without the other.

Kevin Le Gendre is a journalist and broadcaster with a special interest in black music. He contributes to Jazzwise, The Guardian and BBC Radio 3. His latest book is “Hear My Train A Comin’: The Songs Of JImi Hendrix”.

Header photo: Johnny Hartman, 1948. New York. Photo: Photo by PoPsie Randolph/Michael Ochs Archives via Getty